Between the sweeping job cuts across Big Pharma, falling stock prices, stalled drug approvals, safety problems with drugs like Avandia and an expected avalanche of generic competitors to billion-dollar brand-name drugs, it’s certainly starting to look like the traditional drug industry’s best days are behind it.

Between the sweeping job cuts across Big Pharma, falling stock prices, stalled drug approvals, safety problems with drugs like Avandia and an expected avalanche of generic competitors to billion-dollar brand-name drugs, it’s certainly starting to look like the traditional drug industry’s best days are behind it.

In fact, good news is pretty much in short supply no matter where you turn. Consider just this litany from this AP story (courtesy of the Baltimore Sun) I linked to a few days ago:

J&J’s plan to cut up to 4,800 jobs follows news of tens of thousands of job cuts at Pfizer Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., AstraZeneca PLC, Merck & Co. and Schering-Plough Corp.

Pfizer, the world’s biggest drug company, is eliminating 10,000 jobs, 10 percent of its work force. Merck is shedding 7,000 jobs, AstraZeneca is slashing 7,600 positions, Schering-Plough has furloughed about 1,100 manufacturing workers, and Bristol-Myers Squibb will cut an unspecified number of jobs by year’s end.

Now ponder yesterday’s installment from the NYT’s Stephanie Saul:

The nation currently spends $275 billion a year on prescription medicines. But over the next five years, analysts forecast a golden era for generic drugs, as patents begin to expire on brand-name medications with more than $60 billion in combined annual sales. That will open the door to copycats that may be 30 percent to 80 percent cheaper.

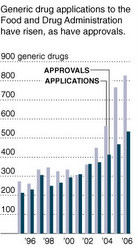

Or just look at the NYT’s graph of generic-drug approvals, part of which I’ve reproduced at the left.

Or just look at the NYT’s graph of generic-drug approvals, part of which I’ve reproduced at the left.

It’s hard not to feel just a tingle of Schadenfreude in all of this. Whatever your feelings about the drug industry, there’s no question that it has lectured us for years that high U.S. drug prices and its ceaseless hawking of pills were crucial to sustaining a steady supply of innovative new medicines. It has insisted that ever-rising drug prices make possible the vast sums the industry devotes to R&D every year. And it has steadily and effectively beaten back every consumer measure that might have jeopardized its ability to set high U.S. drug prices, arguing that Medicare price bargaining, legal imported drugs and any federal effort to ensure “reasonable” prices for drugs largely derived from taxpayer-supported research could mean the end of our pharmaceutical Golden Age.

And yet it’s all coming undone anyway, because it turned out that most of the big drug companies weren’t anywhere near as innovative as they claimed. Instead of turning their still-enormous cash flows into ground-breaking new drugs, pharma companies are for the most part stalking the landscape, looking for the next promising biotech drug to snap up — at least when they’re not defending their existing blockbusters against safety problems or firing sales reps who apparently went too far in hawking their drugs.

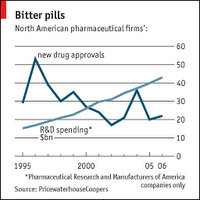

For a graphic illustration of just how much Big Pharma productivity has suffered over the past decade, consider the graph at left, which is from this Economist piece that argues that the entire industry need to rethink its business model. That seems like a no-brainer to me; as Ogan Gural points out over at Life Sciences Daily, the blockbuster model is “rapidly leading to extinction.”

For a graphic illustration of just how much Big Pharma productivity has suffered over the past decade, consider the graph at left, which is from this Economist piece that argues that the entire industry need to rethink its business model. That seems like a no-brainer to me; as Ogan Gural points out over at Life Sciences Daily, the blockbuster model is “rapidly leading to extinction.”

Among other things, Ogan cleverly notes that all blockbusters have an Achilles’ heel, one that renders the entire model suspect so long as our understanding of human biology and drug side effects remains limited:

[T]he massively indiscriminate target populations and the long-term, chronic administration that makes these blockbusters in the first place also renders them extraordinarily susceptible to safety issues. It boils down to simple statistics: if you give a drug to enough people for a long-enough time, you’re bound to get some safety problems. Hence the solution to the business problem has been for companies (such as Roche acquiring various diagnostics firms) to embrace personalized medicine which also holds the promise (but not the entire key) to solving the safety problem.

Biotech, of course, has been largely spared in this bloodbath — Amgen’s troubles excepted — because the industry’s companies tend to focus on disease “niches” instead of trying to come up with one-size-fits-all drugs. If, in fact, personalized medicine does start to take off — something that’s been a long time in coming — we can probably expect the balance of power to shift even further in biotech’s direction.

Merrill Goozner has some additional thoughts on pharma’s troubles here; he thinks that the dominance of drug companies in our public healthcare discourse is coming to an end as attention shifts to the debate over general healthcare reform.