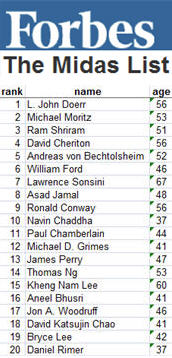

Each year, Forbes publishes the list of top 100 investors, called the Midas List (see our coverage, and full list).

Each year, Forbes publishes the list of top 100 investors, called the Midas List (see our coverage, and full list).

It is closely watched by venture capitalists eager to see where they are in the pecking order. Forbes writer Erika Brown, leader of the ranking process, faces a barrage of calls and emails from investors each year, complaining how she has treated them. We spoke with Erika Brown yesterday to ask a few questions about Forbes’ ranking. Our Q&A is below. First, here’s what we do know about the ranking: Forbes looks at investor track records for the past five years. It looks at the market value of companies they backed, at the time of the companies’ exit, whether an IPO or an acquisition. It also looks at the amount of capital invested to get there. Less attention is given to the change in value of each investment since going public or being sold. Ranking also depends on a candidate’s length of involvement in, and depth of influence on, a company, which Forbes assesses through hundreds of interviews and surveys.

VentureBeat: A reader at VentureBeat claims in comments that the Midas List ranking method is problematic because investor like James Wei and Mike Orsak made the list in former years, even though they didn’t have very big exits. I don’t want to single them out, and I don’t even know if the reader’s claims are true, but how do you respond to these incessant criticisms about flawed rankings?

Brown: We have a team — two statisticians and three in editorial — who work on this project for months. It’s a really rigorous process. We try to improve the list every year. We added a new piece of information this year: The total amount of venture capital raised by a company. Until now, this was only available to us in SEC filings, and applied only to a small number of exits, namely public offerings. Most exits are acquisitions, and there’s little public data about those. The National Venture Capital Association and Thomson Financial agreed to share this with us for the first time. Now we have data for pretty much every deal out there. That alone made a huge change in the rankings.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

VentureBeat: How did that improve things?

Brown: For instance, Stumbleupon. The company raised $2 million in venture capital, but its acquisition price when it was sold to Ebay was $75 million. That’s a 37x return. [Investors in StumbleUpon] are going to get a lot more credit. Last.FM raised $5 million, and it had a a $280 million acquisition. That’s a 53x return. On the other hand, companies like UGO, which raised $89 million, and sold for $100 million — that would count for very little. Companies like Vonage and SMIC are high up on the list of exit values, but we thought it was unfair to celebrate those deals above deals that may have had smaller exit valuations but which were more profitable for investors. SMIC raised $1.674 billion, and its market cap was $6 billion at IPO. But it declined from there. That’s another piece of the formula: “Value, if held.” We look at the delta [change] between exit value and the current value of a stock in a public company, or if it’s a private company, the delta in the stock of the acquiring company. We want to highlight people who build lasting, durable companies. We don’t want to celebrate guys who are good at flipping or timing the market, and who leave other people holding the bag.

VentureBeat: So in this case, Danny Rimer, of Index Venture, who invested in Last.Fm, rocketed up the rankings?

Brown: It kept him at the top.

VentureBeat: If five investors back a successful company, how do you treat them? Do you give them all equal credit for the deal, even though one of the investors may have put in more work?

Brown: No. Sometimes I call the entrepreneur [to ask which VCs should get credit]. If you were a very early investor and a board member, and you recruited the CEO independently and you introduced the acquirer to the company that led to the deal, you get a lot more credit than if you were in the F round of funding and came on just before the IPO. A lot of venture capitalists do try to inflate their rankings by giving us misleading information. Some times we get five VCs who claim credit for the same deal. We try to get the most accurate picture possible, by researching public documents and conducting hundreds of interviews with venture capitalists and entrepreneurs.

VentureBeat: How do you feel about the methodology as it stands now? Where are the main points of weakness in your view, and how much can those areas be addressed?

Brown: This is a very well cloaked industry, and until venture capitalists become transparent with their reporting, there’s only so much information we have at our disposal. We do the best job out there in my opinion in even attempting to rank these guys on a purely numerical basis. No one else does this. If you look at other rankings of venture capitalists, it’s based on popularity and public perception. Ideally, one day we’ll get access to the amount of venture capital each firm put into every company and how much they took out, but unfortunately the SEC doesn’t have the same say over venture capital as it does public companies. That information just isn’t available to us in a enough cases where it would be statistically relevant and fair to use [for the ranking]. There’s information for public companies, but [IPOs account for] a small percentage of exits in venture capital. We had 86 IPOs last year, 304 M&A deals.

VentureBeat: Why is David Cheriton, a Stanford professor, so high on the list, when he’s not really a professional investor, and some would argue he’s a one-hit wonder, having invested in Google, along with many other guys?

Brown: He made a boatload of money. He was an angel investor in Google, instrumental in the Google process. Larry and Sergey went to him first. But he’s also an advisor and a shareholder in a number of other companies too. And he’s a billionaire.

VentureBeat: Why are bankers like Michael Grimes, Paul Chamberlain on the list, or lawyers like Larry Sonsini?

Brown: That’s another question I get all the time. We think about that every year. Some people have a problem with it. We want to appeal to a broader readership that is really interested in all the power brokers in this industry. If you want to take a company public, you want to know who Michael Grimes is. If you want to make an acquisition, you want to know who Larry Sonsini is.

VentureBeat: Some would argue these service providers are commodities. Do they add that much value?

Brown: I don’t think they are commodities. A really good banker and a really good lawyer are going to help you get a better price for your acquisition. And a really good banker is going to help you get a higher asking price for your stock, if you go public.

VentureBeat: But how do you rank them — I mean, Google was going to be successful regardless of its banker.

Brown: They have a different questionnaire. They only get points if they are leader in the deal. But they don’t get as many points in a deal, as say a venture capitalist who is an early stage investor. In order for a banker or a lawyer to make our list, they have to have many more deals. Our list shows who those power brokers are, because there are so few of them, and it takes a lot of deals to get on [the List].

VentureBeat: Silicon Alley Insider complains there’s no New York investors included, implying you have a West Coast bias? How do you respond?

Brown: This is not a list that ranks the regional best. We’re on the look out for the biggest, blockbuster deals period.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More