A growing number of game makers on Facebook are making money from virtual goods — from poker chips to virtual clothes that users can buy or earn while playing gaming applications with their friends on Facebook. The combined ecosystem of these game developers and other companies supplying services to them could generate half a billion dollars in revenue in 2009.

A growing number of game makers on Facebook are making money from virtual goods — from poker chips to virtual clothes that users can buy or earn while playing gaming applications with their friends on Facebook. The combined ecosystem of these game developers and other companies supplying services to them could generate half a billion dollars in revenue in 2009.

That’s significant, considering third-party applications on Facebook have been viewed as gimmicks making no significant revenue. Facebook itself appears headed toward the $500 million revenue mark this year, mostly through advertising.

Before diving into some of the platform revenue numbers, lets be clear: These numbers are very hard to come by. Most companies haven’t been willing to say what they’re making. Much of what I’ve heard is based on triangulating between sources. Everything here should be viewed as a rough estimate. The big picture is what’s important: the creation of real, sustainable businesses on the platform. Some other qualifications: Many of these companies are doing well on other platforms, as well, most notably on MySpace and on the iPhone. I don’t have a good window into how much companies are making on those platforms, nor do I have a good idea of how much companies are making through Facebook Connect and other services that let third parties access social network user data from around the web. So here goes….

The virtual goods ecosystem on Facebook

To understand what is happening on Facebook’s platform today, one has to understand how the ecosystem works. The first, most obvious part is the game developers themselves. Companies large and small create games, from the simple to the complex, that live on Facebook canvas pages. The value Facebook provides here is to make it easy for friends to find games and play them against each other. People already tend to be friends with their real-life friends on the site. They’re using the news feed, profile pages and other communication channels to help them share games with each other. Take, for example, the mafia-genre game called Mob Wars. You can invite your friends to join your mob, and go around committing various crimes and earning points together. Mob Wars, like all sorts of other games on the platform, then lets you use these points to gain virtual items that increase your power.

To understand what is happening on Facebook’s platform today, one has to understand how the ecosystem works. The first, most obvious part is the game developers themselves. Companies large and small create games, from the simple to the complex, that live on Facebook canvas pages. The value Facebook provides here is to make it easy for friends to find games and play them against each other. People already tend to be friends with their real-life friends on the site. They’re using the news feed, profile pages and other communication channels to help them share games with each other. Take, for example, the mafia-genre game called Mob Wars. You can invite your friends to join your mob, and go around committing various crimes and earning points together. Mob Wars, like all sorts of other games on the platform, then lets you use these points to gain virtual items that increase your power.

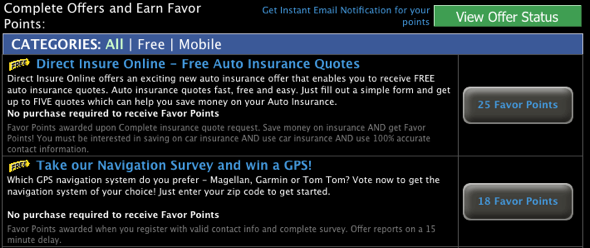

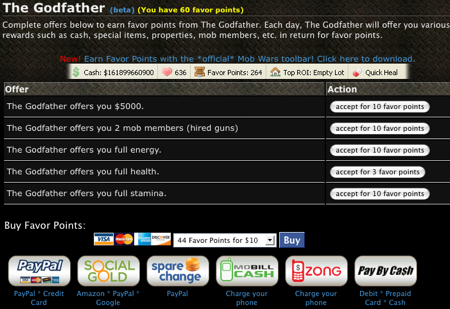

The points concept is where the revenue part comes in for most games. Continuing the Mob Wars example, you can also get special benefits like a virtual pistol or a virtual bag of cash by earning special “favor points” and using them to get these “favors” from the game’s Godfather character. You can buy favor points directly, using web payment service PayPal, mobile payment service Zong, and a variety of others. Or you can earn them. The way you earn favor points is through taking offer-based advertising — essentially, coupons, contests, surveys, software downloads and many other options.

A few companies, led by Offerpal and Super Rewards, provide a set of tools for letting developers integrate these offers into their games. They integrate a range of direct payment systems and offers from advertisers, along with analytics software about offer performance, and other features into a single software package. Game developers can build this software into their games in a matter of hours or days, leaving them most of their time to focus on building games that people like to play.

Once a game gets enough users, these small payments and offers add up. Payments companies take a cut when users buy points through them, and offer companies take a cute of revenue generated from offer advertisers. The developers take home the rest. Mob Wars, for example, currently has more than two million users a month — and has been making millions of dollars for a long time.

Virtual goods revenue

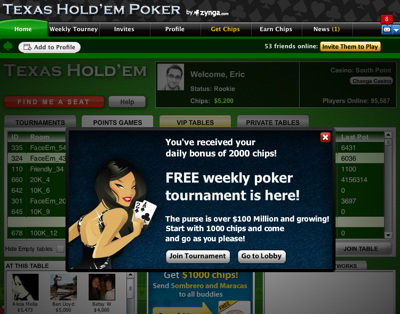

Now, let’s look at who’s making what. The leading game developer is currently Zynga , which offers a range of applications including poker game Texas Hold ‘Em, virtual world YoVille, and a long list of other titles. I’ve heard Zynga was on track to make around $40 million as of this past winter, about half coming from Facebook users, half from its users on MySpace; 75 percent of the revenue at that point was coming from the sale of poker chips. But Zynga’s revenue seems to be growing — it was on a $50 million or $60 million annual run rate as of March, other sources have said. The most recent reports about the company suggest it could make more than $100 million this year.

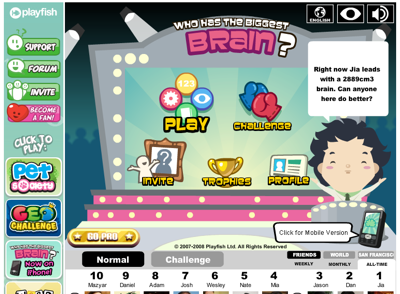

But that’s just one company. Another top gaming company, Playfish, is on track to make around $30 million in 2009, sources said. Another, Playdom, has been making around $10 million per quarter — mostly from MySpace games, though. It has only recently moved on to Facebook, and I don’t know how much it is making there.

In total, the top few developers are likely to make more than $150 million in revenue this year, according to estimates from several industry sources I’ve spoken with. But then there’s the so-called long tail of smaller game developers who are also making money. Around 50 smaller developer teams making between half a million and $1 million a year, comprising the middle tier of the market. That group is followed by another hundred or so developers making between a quarter of a million and half a million dollars. Combined, these smaller developers could bring in revenues of $100 million or more this year.

How does it all add up? “I think it’s a $250 million to $300 million market in 2009, at least” says Anu Shukla, chief executive of Offerpal. “There are some big players and there are some smaller players growing very fast.” Super Rewards chief executive Jason Bailey says that the $300 million number is conservative, and believes platform revenue is headed to half a billion dollars this year. Anecdotally, he says, his company sees a new game developer appear from time to time and start making tens of thousands of dollars a day.

How does it all add up? “I think it’s a $250 million to $300 million market in 2009, at least” says Anu Shukla, chief executive of Offerpal. “There are some big players and there are some smaller players growing very fast.” Super Rewards chief executive Jason Bailey says that the $300 million number is conservative, and believes platform revenue is headed to half a billion dollars this year. Anecdotally, he says, his company sees a new game developer appear from time to time and start making tens of thousands of dollars a day.

But remember that the Facebook platform is littered with applications that have never gotten popular, or were popular at one point but aren’t any more. This is something that even the most popular game developers face. Some of their apps are popular for a few months then lose steam. Figuring out how to build a game that keeps people engaged is a trick that only a few companies have done, and even then not with every game. Other factors, like Facebook constantly redesigning its own interface, can also create and destroy particular applications. An earlier generation of applications relied on appearing on Facebook users’ profile pages, for example, but in a new redesign rolled out last summer, Facebook moved almost all of those applications to a separate, harder-to-find tab within profiles. See this article from last December for a lot more on those issues.

Successful smaller games also seem to hit a sort of ceiling in growth and revenue. So the largest game developers, like Zynga, buy advertising in other Facebook applications. RockYou, a long-time leading developer of its own applications, sells these ads for many gaming companies, targeting ads for games to applications based on similarities of users and their interests. For game developers, the decision to buy traffic is based on them being able to make more money from new users than it costs them to advertise to reach those users. While a cleverly designed game can grow through Facebook’s communication channels, Shukla tells me that it typically needs to buy traffic in order to get millions of users and make millions of dollars.

Perhaps growth in these app-to-app ad sales is one reason why RockYou is so bullish — it can see its own business growing along with the gaming companies. Ro Choy, RockYou’s chief revenue officer, says that the overall run rate for the platform has been on track for $300 million this year, but current growth rates are, same as what Baily said, pushing that number towards half a billion. RockYou itself could make more than $20 million this year, through a mix of these ads and other banner ads on Facebook and other social networks. But that’s less than what Offerpal and Super Rewards are making, from what I’ve heard — both of those companies are seeing Zynga-like revenue in the tens of millions.

Perhaps growth in these app-to-app ad sales is one reason why RockYou is so bullish — it can see its own business growing along with the gaming companies. Ro Choy, RockYou’s chief revenue officer, says that the overall run rate for the platform has been on track for $300 million this year, but current growth rates are, same as what Baily said, pushing that number towards half a billion. RockYou itself could make more than $20 million this year, through a mix of these ads and other banner ads on Facebook and other social networks. But that’s less than what Offerpal and Super Rewards are making, from what I’ve heard — both of those companies are seeing Zynga-like revenue in the tens of millions.

Of course, all of these revenue projections are based on a year that’s not even half over. Rates in revenue growth might not hold up. But it’s been the increasing sophistication of the virtual goods ecosystem — the game developers, the payment companies, the offer companies, the analytics companies like Kontagent — that seems to have spurred recent growth. Many of these companies only really began refining their virtual goods revenue streams in the first part of 2008, and it was only last summer that I’d gathered enough information to get a good idea of what was happening. It has been in the first quarter of this year that many companies have been seeing sharp increases in revenue. The numbers I’ve heard echo an excellent report by Inside Facebook from last month, indicating payment providers have been seeing around a 35 percent increase in both number of transactions and number of dollars in the first three months of this year.

Where the platform is headed

The virtual goods economy faces hurdles. For starters, many of the offers themselves reek of scams — like ringtone sellers who don’t tell users that their mobile phones are going to be billed every month even if they don’t buy more ringtones. A longer-term risk is that people who take offers now might not want to take them later. There are only so many credit card offers that any one person is going to want.

But the dynamic at play — incorporating payments and offers into games — looks like it’s here to stay. For users, offers can be a win-win. I might think that getting a new pistol in Mob Wars will make my friends think I’m cool, and help me beat them at the game, so any way I can get that pistol is potentially good for me. If getting that pistol means signing up for some Netflix rentals at the same time — and if I already want to rent some movies anyway, then so much the better that I do it in the process of getting the pistol. More advertisers are looking at offer-based advertising, and if these companies can really nail the consumer-goods market, you can see how offers might get a lot more valuable. Teenagers might re-up on acne medication as they re-up on ammo, one day.

More generally, virtual goods have already proven themselves elsewhere, especially in web-based virtual worlds like Second Life, Habbo and Gaia, and on Asian social networks. China-based web portal Tencent, for example, made more than $1 billion last year from a variety of virtual goods — like clothing for users’ avatars — that it integrates with its instant message client, social network and games.

Among other western social networks, revenue on MySpace’s platform seems to be the most promising. I don’t have a good view of how much companies are making on it. As the site itself is smaller than Facebook’s, and its application developer community smaller, the overall number is likely less. Some companies have told me that roughly a third of their revenue comes from Facebook, a third from MySpace, and a third from other social networks and social sites. Other companies have been more focused on Facebook and less on MySpace or other sites. Facebook has some 200 million monthly active users, while MySpace has around 130 million. But MySpace has a large user base of some 70 million people in the US, skewed towards people aged 17-24 who are already on MySpace for its entertainment-focused content, and who like playing games. This demographic isn’t just valuable because people in the U.S. have relatively more spending money — many of the offers used in games are intended for U.S. audiences. Some developers, I hear, make twice as much money from the average MySpace user versus the average Facebook user.

Among other western social networks, revenue on MySpace’s platform seems to be the most promising. I don’t have a good view of how much companies are making on it. As the site itself is smaller than Facebook’s, and its application developer community smaller, the overall number is likely less. Some companies have told me that roughly a third of their revenue comes from Facebook, a third from MySpace, and a third from other social networks and social sites. Other companies have been more focused on Facebook and less on MySpace or other sites. Facebook has some 200 million monthly active users, while MySpace has around 130 million. But MySpace has a large user base of some 70 million people in the US, skewed towards people aged 17-24 who are already on MySpace for its entertainment-focused content, and who like playing games. This demographic isn’t just valuable because people in the U.S. have relatively more spending money — many of the offers used in games are intended for U.S. audiences. Some developers, I hear, make twice as much money from the average MySpace user versus the average Facebook user.

In calculating platform revenue, one still has to put virtual goods in perspective. Offers are actually a form of advertising, and other forms of advertising that also seem to be working. Many companies are experimenting with ways to target users with ads based on friend groups, demographic information, and other information. Slide, another app developer that has millions of users on Facebook and other sites, is also making somewhere around $20 million, but through advertising. Flixster, a movie fan app on Facebook and other social networks, as well as a stand-alone site, is making somewhere around $7 million (it only tells me that its been profitable this year). LOLapps, a create-your-own app company that has also gotten big on Facebook, is making around $5 million, source say. Social Media, an advertising network present on Facebook, told me in January that it made more than $15 million in revenue last year. Other gaming companies, like SGN, started out strong on Facebook but have since refocused elsewhere (SGN is now mostly focused on building iPhone applications, albeit using Facebook Connect integration, and I hear it hit profitability this month).

Finally, one has to wonder what Facebook’s own plans are for any sort of virtual goods or currency — at least beyond its gifts store, and its experimental comment-credit system. It has said it’s looking to offer a currency that developers could potentially use across any Facebook app, but I haven’t detected anything more concrete in recent months. MySpace, however, is moving forward with its own virtual goods plans, possibly including a universal currency. Hi5, a smaller rival social network, has already transitioned towards becoming a “social entertainment” site based around games and virtual goods.

So the question for Facebook is: How much money is it leaving on the table by not making money from its platform? And the question for developers is: how big can the opportunity on Facebook and other social gaming platforms grow to be one day?