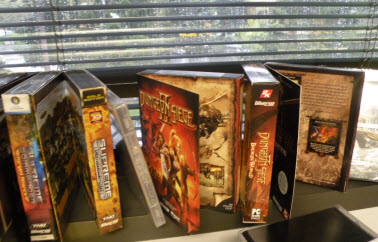

Chris Taylor is a goofy character in the game business. That’s why he was a fine emcee at our recent GamesBeat 09 conference. But he has a serious side as the founder of Gas Powered Games, a maker of real-time strategy games that has weathered big changes in the PC game business. Taylor’s games –- including Total Annihilation, Dungeon Siege, Supreme Commander, and the recent Demigod — have sold more than 6 million copies. We caught up with him in his office at Gas Powered Games in Redmond, Wash., where we talked about what it takes to survive as a game developer for so long.

Chris Taylor is a goofy character in the game business. That’s why he was a fine emcee at our recent GamesBeat 09 conference. But he has a serious side as the founder of Gas Powered Games, a maker of real-time strategy games that has weathered big changes in the PC game business. Taylor’s games –- including Total Annihilation, Dungeon Siege, Supreme Commander, and the recent Demigod — have sold more than 6 million copies. We caught up with him in his office at Gas Powered Games in Redmond, Wash., where we talked about what it takes to survive as a game developer for so long.

VentureBeat: You’ve kept the doors open here for 11 years at Gas Powered Games. How hard has it been to do that?

VentureBeat: You’ve kept the doors open here for 11 years at Gas Powered Games. How hard has it been to do that?

Chris Taylor: It’s actually been very hard. There are times when it’s not hard because things are going very well and you’re focused on making games. As we went into this recession, the sands started shifting under our feet. The model is changing. We are getting into digital distribution. Publishers are figuring how to manage their investments for games with enormous budgets. They wonder how to create original games without betting the farm. Developers are at the back of that bus. Whatever happens at the high level trickles down to us. We have to figure out how to make our business work in that context. We aren’t a grocery store. We don’t have continuous income.

VB: You live from project to project?

CT: We live from project to project. What happens if a project gets canceled? You may have 30 to 40 people working on it. Do you let them go? That’s hard. They are part of your company’s culture. It took all that work to hire them. You can’t just hire and fire and be devil-may-care about the morale. This is why outsourcing has been a good development in our industry. It helps with the ups and downs of production. It’s been very hard at times. But we are getting better at managing the unknown.

VB: What’s the hardest problem?

VB: What’s the hardest problem?

CT: The hardest problem is capitalization. I started the company with $120,000. We had five guys in my dining room. I didn’t take outside investment. I wanted to own my own intellectual property, or the game we created. Now it may take $5 million to $10 million to do a worthwhile title. You have to operate in the old music recording industry model. You take an advance against royalties. If you take a 33 percent advance, that means you borrow from the [publisher] at a 300 percent interest rate. If it takes $10 million to make the game, the publisher has to net $30 million. Then you’re even. Developers are really operating in a tough model. If you need the royalties to make a profit, how can you do it?

VB: Who bought into your plan?

CT: Microsoft was the first publisher to sign up. We were creating Dungeon Seige. I love them for that. We were only a few people, starting the company around that project. We grew to 30 people under that title. That was a hit. We started growing. We were doing two titles at once, Dungeon Seige 2 and Supreme Commander. We learned a valuable lesson. Having too many games in production at once was not very fun. The administrative overhead of running a 100-person plus company is large. I was spending my days managing the company, not designing games. That was a failure.

VB: What years are you talking about?

VB: What years are you talking about?

CT: We were founded in 1998. By 2005, we staffed up. At that point, we were working with THQ. We had three games going at once at one point. I dialed the company back. As things slowed down, as games shipped, or as a game got canceled, we took our foot off the gas pedal. Then we embraced outsourcing. If you put all of your art production in house, that’s 25 or 30 people. But if you outsource two art teams, then you’re operating much more efficiently. I could fill up our office space with artists. It would be more impressive from an ego standpoint, but not from a good business standpoint. It’s better to work with a smaller brain trust, outsource the work, and then bring it back here and assemble it.

VB: During this whole time, you’ve had to deal with big waves in the industry. PC games have been sinking, at least single-player games, as console games take over. And the costs of making games have been skyrocketing.

CT: When a PC game increases in cost, you may need 50 to 60 people to finish it. How do you fund that team into the next cycle? In the last 20 years, we’ve learned you need a concept phase [and a pre-production phase]. It could take six months or a year. So during that time, your artists would be sitting idle. You can’t have them on your staff. We realized we had to move toward the movie-making model, where they had contractors working from project to project. Steven Spielberg operates that way. It works really well for movies. During [the concept phase], I have just a lead artist. [In pre-production, I have two to four artists]. Then that [core art team] communicates what we need to the outsourced team. Those studios are [eventually] likely to be local, rather than overseas, because everybody will need them.

VB: How did you produce Demigod?

VB: How did you produce Demigod?

CT: Our idea was that if we funded the game ourselves, we could fetch a better deal when it came to find a publisher. It turned out that we decided we would need a publisher, late in the process. We didn’t have the chops to launch worldwide on our own. By funding it ourselves most of the way, we got tremendous creative control. We didn’t have to have a publisher approve our milestones. We created the exact game we wanted to make. When it was far enough along, we found a publisher. We started it at the beginning of 2007. We worked on it for 15 months before we found the publisher. It was about two years and three months from start to finish.

VB: How did you finance it?

CT: We borrowed money to fund it. The idea was we would pay the money back with proceeds from the game.

VB: How did the launch go for you?

CT: I haven’t gotten the numbers yet.

VB: What’s your post-mortem on Demigod and your approach?

VB: What’s your post-mortem on Demigod and your approach?

CT: I don’t recommend it. You should either completely fund a game or don’t do it at all. If you fund a game 95 percent of the production cycle, that’s not good. You took on all the risk, but you give up the ability to capture the upside because you have gone through a middleman. I don’t recommend self-funding the game unless you’ve got other revenue sources or a direct distribution channel.

VB: But you got independence out of this?

CT: We got creative independence. If that’s the itch you’re scratching, you can get that from this kind of approach. We hope that the game is financially successful too. It’s too early. We just don’t know. We had some multiplayer difficulties that have been ironed out. People are having some good four-vs-four games on the Internet. By the time E3 rolls around, [most of the multiplayer issues will be solved], and the game could continue to sell through the rest of the year.

VB: Your other projects are going to be traditional publishing deals?

CT: Yes. We still need to work closely with our publishing partners. Until digital distribution comes along, publishers are going to be an integral part of our business.

VB: OnLive (the video games on demand service) may be coming. Isn’t that the light at the end of the tunnel for you?

CT: You still have the banking component to worry about. The publisher handles marketing, testing, PR and distribution. But it’s fundamentally your banker still. If you bring OnLive in, you replace distribution and retail. But someone still has to bankroll it.

VB: So the retailer gets cut out, but not much changes?

CT: Not that I can tell, unless OnLive wants to fund games. Does Comcast fund [television shows?] The thing that might fundamentally change the industry, for the artist to get more control, is if the artist community could become more proficient at business and control the money. If that was going to happen, it would already have happened in books, film, and TV. And it hasn’t happened. The money winds up in the hands of the business people. And the artist is flailing on the side, screaming about wanting more control. There’s always that tension between the business person and the artist. It’s comical.

VB: But existence is a big accomplishment for a developer. You’ve survived 11 years. Since July, more than 60 studios have closed or had layoffs.

CT: Is that so? Wow. You know that joke, 40 is the new 30? Not failing in business is the new succeeding in business. If you’re not closing your doors, you’re a success. There is a lot of truth to that. But it’s not fun living on the edge.

VB: You still get to go take another swing at getting a hit.

CT: Yes. With what we’ve learned in the last year, with the business shifting into neat new ways you can distribute content, we are seeing a future with great possibilities. My wife sells things online on a site called Etsy. You make things and sell them there. It’s an interesting community that supports each other. It cuts out the middleman. The Internet does some amazing things.

VB: If you want to see the game industry mature, what does that mean to you?

VB: If you want to see the game industry mature, what does that mean to you?

CT: What’s immature about our industry? The way I described how Hollywood makes movies. You staff up, you build something, you staff down. That’s maturity. The banking should come from multiple sources. We need more expertise in our industry the way that Hollywood has expertise. It sounds like I’m envious of Hollywood. But I just want to make games. You notice when the Oscar winners get up on stage, they’re not a bunch of 20-year-olds. It’s people with gray hair, with a lot of experience. About 20 years ago, I was that 21-year-old kid working on games. Now, here we are, we are starting to finally see some gray hair in our industry.

VB: I don’t see any gray hair on you. Are you coloring?

CT: Uh, no. Our industry will mature when everybody gets gray hair.

VB: How would you start a game company today?

CT: I would save up a bunch of money to live on for two years. Then I would develop an iPhone game. I would start building relationships with Sony and Microsoft. I would roll that game into an Xbox Live title or a PlayStation network game. Then I could make it into a downloadable game on the PC. The poster child for that is The World of Goo. Read about that game. Drink lattes. Put your feet up. And build your game. To do that, you need a couple of years in the bank and you have to live in your parents’ basement. You can’t start out with $30 million for a console game. @*%&$^, Roland Emmerich didn’t wake up one day and create Independence Day. We can’t be delusional about trivializing what it takes to make these big games.

VB: Does the game industry’s future look brighter than ever?

CT: I dare say it does. And I’m going to give 46 percent of the credit to Apple. Apple has inadvertently backed into a key position in interactive entertainment. Maybe Facebook gets 18 percent. I don’t give them quite as much credit because of the quality of the experience delivered. I’m playing very little.

VB: You stopped playing when Scrabulous shut down?

CT: Fricking Scrabulous. You need a solid plan to get above the noise on Facebook. The game industry is going to have a great five years. But like on Facebook, it’s going to get harder to get a game noticed because competition is getting more fierce because the playing field is being leveled. The development tools are so good. People with arguably less time under their belt can get something done. It’s like the sky filling up with pilots.

VB: And what is Gas Powered Games’ clear patch of sky?

CT: We like real-time strategy. Demigod is just a glimpse into the future of what we can build in that space. It’s not building a base and mining gold. There is almost a whole genre that can open, just like Battlefield 1942 busted open a whole sub-genre of first-person shooter games. It’s like a different experience. We’ve done well so far. But I haven’t had my Gears of War or my Halo. I can’t go take off for an island in the Caribbean.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More