The implosion of Infinity Ward, one of the best videogame studios ever founded, is the latest chapter in a long saga intertwined with the history of intense combat video games.

The implosion of Infinity Ward, one of the best videogame studios ever founded, is the latest chapter in a long saga intertwined with the history of intense combat video games.

A lawsuit filed by the studio’s co-founders last week against parent company Activision Blizzard was a sad milestone at a studio that has come to be cherished by millions of hardcore game fans.

In the beginning, there was Saving Private Ryan. Steven Spielberg’s horrific World War II movie opened in 1998 and shocked audiences with its realistic, horrifying portrayal of the D-Day landings at Omaha Beach and the subsequent fighting in the liberation of France.

In the beginning, there was Saving Private Ryan. Steven Spielberg’s horrific World War II movie opened in 1998 and shocked audiences with its realistic, horrifying portrayal of the D-Day landings at Omaha Beach and the subsequent fighting in the liberation of France.

Spielberg, whose move studio Dreamworks had spun off a Microsoft-backed games subsidiary, Dreamworks Interactive, in 1995, wanted to re-introduce young people to the horrors of war and the sacrifices made by those that Tom Brokaw called The Greatest Generation. He thought a video game based on the movie would reach younger audiences with the same kind of message. Peter Hirschmann served as the key writer and producer. A hit PlayStation version of Medal of Honor debuted in 1999.

But after the dismal failure that year of the heavily-hyped dinosaur-fighting game Jurassic Park: Trespasser, Spielberg lost his appetite for games. He sold DreamWorks Interactive to Electronic Arts in 2000. During this time, a team that ultimately became the Spark Unlimited studio managed to get out a couple of Medal of Honor games out on the Sony PlayStation. That team included Craig Allen, Adrian Jones, and Scott Langteau.

But the most ambitious Private Ryan project, a PC game, survived the transition. EA asked id Software, which had made the World War II-themed Wolfenstein games, if it wanted to make a another game dubbed Medal of Honor. Id’s veteran developers, their hands full, pointed to a promising new game company in Oklahoma called 2015 Studios, founded in 1997 by Tom Kudirka. EA commissioned 2015 to make the high-end game on the PC.

Dale Dye, a decorated combat veteran who was an advisor on Saving Private Ryan, gave the young 2015 developers a lot of advice about how to create a realistic combat scene. He knew, for instance, exactly how big the explosions were when a WWII grenade went off, and what it sounded like when a bullet whizzed by your head. The team was inspired by Spielberg’s movie and Dye’s experiences to make a memorable game.

Dale Dye, a decorated combat veteran who was an advisor on Saving Private Ryan, gave the young 2015 developers a lot of advice about how to create a realistic combat scene. He knew, for instance, exactly how big the explosions were when a WWII grenade went off, and what it sounded like when a bullet whizzed by your head. The team was inspired by Spielberg’s movie and Dye’s experiences to make a memorable game.

In 2002, EA launched Medal of Honor: Allied Assault. It was an outstanding game that made players feel as if they were inside the beach landing scene in Saving Private Ryan. As a player, you quickly realized that you were not invincible as the Germans sprayed nonstop machine gun and mortar fire from the bluffs above. Instead of charging into the fray, you had to find cover to survive. But just like the movie, you were still a dead man unless you kept moving forward. The game set a new bar for realism in war combat.

2015 Studios eventually went on to work on a Vietnam war game, Men of Valor. But there was a faction that didn’t like working in Tulsa and didn’t like the way 2015 was run. After the Medal of Honor game shipped in 2002, Grant Collier and Vince Zampella left 2015 to set up their own game studio, Infinity Ward. They started out in Santa Monica, Calif., as close to the beach as possible. Their friend Jason West joined them, as did a total of 22 former 2015 employees. They got their startup money from Activision, a game publisher run by Bobby Kotick, who wanted them to get Activision into the then-hot genre of World War II shooting games. Activision gave them $1.5 million for a 30 percent stake. At the time, that was plenty of money to make a PC game. The deal made a lot of sense because the Infinity Ward crew had proven it could make an outstanding game. And Kotick was always happy to give seed money for teams that were willing to break away from Electronic Arts, his chief rival.

The team was full of history buffs who had studied the maps of the D-Day landings and had carefully decided where to put foxholes and trenches in their games. With a team of 25, they worked hard to produce a game titled Call of Duty. Critics were sure it was just a clone of Medal of Honor. But the game was inspired by the most intense battle scenes in movies such as Enemy at the Gates, Band of Brothers and Saving Private Ryan.

The team was full of history buffs who had studied the maps of the D-Day landings and had carefully decided where to put foxholes and trenches in their games. With a team of 25, they worked hard to produce a game titled Call of Duty. Critics were sure it was just a clone of Medal of Honor. But the game was inspired by the most intense battle scenes in movies such as Enemy at the Gates, Band of Brothers and Saving Private Ryan.

The game launched in October, 2003, on the PC. Gamers loved it and felt as if they were inside a combat movie as they played through the relentlessly intense combat scenes across the British, American and Russian armies in World War II. In each case, you played a vulnerable infantry soldier amid a sea of enemies.

Activision was thrilled at the reception and agreed to acquire the remaining 70 percent of Infinity Ward in 2003 for $3.5 million. While Activision now held the purse strings for resources, Kotick let the team run independently. He wanted to “preserve the magic.” Infinity Ward began work on a sequel. About three months into that work, Microsoft contacted Activision, asking if it had any games it could make for the launch of a new game console: the still-secret Xbox 360.

Microsoft had a big problem. Halo 2, the sequel to the big sci-fi shooting hit on the original Xbox, had not yet shipped. It was clear that Halo 3 would not be ready, as originally planned, for the launch of the Xbox 360 in the fall of 2005. Microsoft’s top game executive, Robbie Bach, had decided that the company was not going to delay the launch. Microsoft assumed Sony and Nintendo would launch new consoles in 2005, and Microsoft could not be late. So Microsoft needed an outstanding shooting game for the console. Bach’s team asked Activision to make Call of Duty 2 a launch title for the Xbox 360.

Collier told me in an interview a few years ago that he was ecstatic about the request from Microsoft. His team wanted to make leap from PC games to the new consoles. Launching with the Xbox would erase what Infinity Ward felt was the stigma that they were a PC game maker only. Infinity Ward kept its PC version going, but then it hired like crazy and broke off a team to make the console version. They decided the Xbox game would share the same art as the PC version, but the control scheme would be very different. The pressure was on because there were less than two years to go before the console launch.

Collier, West and Zampella tripled the size of their studio to about 75 people. Their lead engineers went to Redmond, Washington, to learn the specifications of Microsoft’s console hardware, which was still under design at the Advanced Technology Group within Microsoft’s Xbox division.

Collier, West and Zampella tripled the size of their studio to about 75 people. Their lead engineers went to Redmond, Washington, to learn the specifications of Microsoft’s console hardware, which was still under design at the Advanced Technology Group within Microsoft’s Xbox division.

Infinity Ward decided to take a very big risk that would characterize its approach to doing big games. Even though they weren’t sure exactly what the Xbox 360 would be able to do, they decided to create a game that would tax all of the console’s theoretical capability, maxing out its ATI graphics chip and its triple-core IBM microprocessor.

The result was that their game had special effects, such as smoke from smoke grenades, that other games didn’t have. That smoke changed the game’s tactics. Players could toss smoke grenades in front of machine guns and then charge into dangerous streets to clear them. It was, Collier said, “eye candy at 60 hertz.” Also, the game maps were not linear paths as previous games had. They were environments, such as towns, where you could take any path you wanted to clear the whole space of enemies. Again, that allowed players to use realistic combat tactics of moving forward until they hit danger spots; then they could outflank the enemies and take them out from the side or behind in ways the game’s creators had not pre-programmed. This made the design of each level much harder, but it paid off.

Infinity Ward also put serious effort into putting artificial intelligence into its enemy soldiers. If a player stayed too long in one spot, the enemies would gather and outflank or encircle him just as in a real battle. The player also had intelligent squad mates who had to stay out of the real player’s way and yet guide him to the battle’s objective. All of this extra programming pushed the budget for the game toward $30 million. That was a big bet by Activision, which had to approve the game’s direction and budget.

When I saw the result in 2005, I was stunned at how good it was. Peter Moore, who then headed Microsoft’s Xbox business, showed me a demo where a soldier prepared to kick down a door, only to be sprayed by bullets that burst through the timber from the other side. The scene was a “cinematic,” a pre-canned film rather than one rendered in real-time. Yet it seamlessly melded into a game scene thatI could play. The integrated cinematics created the feeling that you were inside a movie-like scene and yet playing a game at the same time.

When I saw the result in 2005, I was stunned at how good it was. Peter Moore, who then headed Microsoft’s Xbox business, showed me a demo where a soldier prepared to kick down a door, only to be sprayed by bullets that burst through the timber from the other side. The scene was a “cinematic,” a pre-canned film rather than one rendered in real-time. Yet it seamlessly melded into a game scene thatI could play. The integrated cinematics created the feeling that you were inside a movie-like scene and yet playing a game at the same time.

The Infinity Ward team finished the game under a punishing schedule. When the Xbox 360 debuted in the fall of 2005, Call of Duty 2 was ready to go. It was an instant hit. Infinity Ward’s big game blew away the competition. About 85 percent of the initial Xbox 360 buyers also bought Call of Duty 2. Only a handful of studios were able to master the programming tricks of the Xbox 360 in time to come up with launch titles. Infinity Ward’s game, clearly the best, outsold all of the others. The Call of Duty 2 game sold more than 1.4 million units in its first year.

By this time, Activision already knew that it had a huge hit on its hands. It began to alternate the Call of Duty franchise between Infinity Ward and another developer, Treyarch, which had also been acquired by Activision. Infinity Ward led the franchise by creating a new game technology, or engine, at the same time it was creating a new game. Treyarch took the completed engine and then made another Call of the Duty game with it. Treyarch’s challenge was to move beyond typical expansion packs and put its creative work on an equal footing with Infinity Ward. Spark Unlimited was also tapped to create Call of Duty title, Call of Duty: Finest Hour. [The Spark relationship also led to litigation]. This took the pressure off of Infinity Ward, which could then take a couple of years to make every game.

By this time, Activision already knew that it had a huge hit on its hands. It began to alternate the Call of Duty franchise between Infinity Ward and another developer, Treyarch, which had also been acquired by Activision. Infinity Ward led the franchise by creating a new game technology, or engine, at the same time it was creating a new game. Treyarch took the completed engine and then made another Call of the Duty game with it. Treyarch’s challenge was to move beyond typical expansion packs and put its creative work on an equal footing with Infinity Ward. Spark Unlimited was also tapped to create Call of Duty title, Call of Duty: Finest Hour. [The Spark relationship also led to litigation]. This took the pressure off of Infinity Ward, which could then take a couple of years to make every game.

After Call of Duty shipped, Infinity Ward’s developers immediately went back to work on another engine and another game, while Treyarch picked up the Call of Duty 2 engine and started working on Call of Duty 3. They launched that game for Activision in 2006. It did well, satisfying the fans of the genre.

But Infinity Ward started working on something altogether different: A combat game set in modern times. At a time when the U.S. was at war in Iraq And Afghanistan, it was sure to hit home. In November, 2006, Activision extended the employment contracts for Infinity Ward’s leaders to ensure their dedication to the game.

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, debuted in October, 2007. It was a monster hit, selling more than 13 million copies over the next two years. By this time, Infinity Ward had more than 100 employees. In the game industry, there were very few teams with multiple blockbusters behind them. So Activision’s heavy investment in resources was worth it, as Infinity Ward had become as rare among studios as id Software, Epic Games, and EA’s DICE studio in Sweden.

Modern Warfare once again had the Infinity Ward signature. It had outstanding realism in its graphics. It had a tight story about the pursuit of terrorists. And every scene was riveting. There was no boring stuff in it. In one scene, you had to escape a sinking ship as water poured in and alarms were blaring. As a rescue helicopter takes off, you had to make a risky jump onto its open entry ramp. No matter how well-timed your leap, you barely made it. The commander grabbed you and pulled you in.

Modern Warfare once again had the Infinity Ward signature. It had outstanding realism in its graphics. It had a tight story about the pursuit of terrorists. And every scene was riveting. There was no boring stuff in it. In one scene, you had to escape a sinking ship as water poured in and alarms were blaring. As a rescue helicopter takes off, you had to make a risky jump onto its open entry ramp. No matter how well-timed your leap, you barely made it. The commander grabbed you and pulled you in.

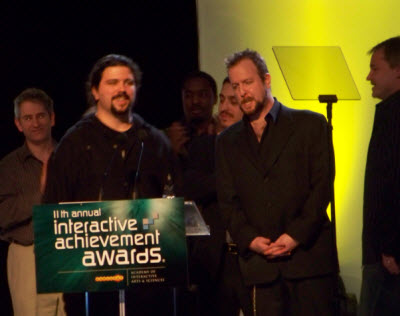

The game won big awards, such as the Game of the Year at the Dice Summit’s Interactive Achievement Awards (pictured, with West on the left, Collier in the middle and Zampella on the right). The accolades rolled in.

The game was so successful that it propelled  Activision into the big time. In December, 2007, the company announced an $18 billion dollar deal with Vivendi Universal’s game division. The merger combined Activision — with assets ranging from Spider-Man to Call of Duty — with Vivendi Games’ Blizzard Entertainment, which had its own huge hits in World of Warcraft, Diablo and Starcraft.

Activision into the big time. In December, 2007, the company announced an $18 billion dollar deal with Vivendi Universal’s game division. The merger combined Activision — with assets ranging from Spider-Man to Call of Duty — with Vivendi Games’ Blizzard Entertainment, which had its own huge hits in World of Warcraft, Diablo and Starcraft.

The combined entity became the world’s biggest independent video game company, and Kotick became its chief executive. The mega merger was just another indicator of how massive and mass-market the video game industry had become.

Treyarch, meanwhile, grew up into a first-class studio as well. In 2008, it launched Call of Duty: World at War, a World War II game set in the Pacific theater. That game was another outstanding hit. The Call of Duty franchise was becoming an annual blockbuster.

But burnout was becoming evident. About a year ago, Collier, the man who was the head spokesman for Infinity Ward, left the company. There was no announcement. His departure was quiet, and there was no explanation. According to a lawsuit filed by West and Zampella last week, the leaders were worried about the growing interference from the parent company. They were not eager to start work on Modern Warfare 2. They wanted to do original games, and they felt the break-neck pace of doing games so fast would burn out the crew.

They were also starting to feel Activision wasn’t given them their fair share of compensation from the games’ sales.

Activision was making billions of dollars in revenue from Call of Duty. It entered into negotiations with Zampella and West and induced them to take on the sequel. In March, 2008, Activision offered them more money. They extended their contracts through 2011. They promised to deliver Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2 by Nov. 15, 2009.

Activision was making billions of dollars in revenue from Call of Duty. It entered into negotiations with Zampella and West and induced them to take on the sequel. In March, 2008, Activision offered them more money. They extended their contracts through 2011. They promised to deliver Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2 by Nov. 15, 2009.

In return, West and Zampella got complete creative control over any games produced under the Modern Warfare brand name. They were also given creative control over Infinity Ward and the right to operate independently. Activision also promised to give the two men more compensation in the form of royalties and restricted stock grants. The agreement also promised to share money with other Infinity Ward employees.

In a year and eight months, Infinity Ward completed the game. Modern Warfare 2 launched on Nov. 10, 2009, to almost universal critical acclaim. It created a huge controversy because there was a scene where the player, acting as an undercover agent, had to accompany a group of terrorists as they mowed down unarmed Russian civilians at an airport.

In a year and eight months, Infinity Ward completed the game. Modern Warfare 2 launched on Nov. 10, 2009, to almost universal critical acclaim. It created a huge controversy because there was a scene where the player, acting as an undercover agent, had to accompany a group of terrorists as they mowed down unarmed Russian civilians at an airport.

The outcry from critics only generated more sales for the game, which set records of all kinds. Activision Blizzard said Modern Warfare 2 was the fastest selling title in history. To date, it has sold more than 15 million units and generated more than a billion dollars in sales. And Infinity Ward’s Call of Duty franchise, purchased by Activision for $5 million, has generated more than $3 billion in sales. While the rest of the video game industry suffered from the recession, Activision Blizzard prospered.

But even as fans were celebrating, things fell apart. Activision’s lawyers, working with outside legal counsel, initiated an investigation on Feb. 3. At the Dice Summit, Infinity Ward’s Zampella didn’t show for a scheduled talk. Instead, Kotick appeared, talking about Activision’s strategy for fostering talented studios to produce great games. [photo: Elisabeth Caren].

But even as fans were celebrating, things fell apart. Activision’s lawyers, working with outside legal counsel, initiated an investigation on Feb. 3. At the Dice Summit, Infinity Ward’s Zampella didn’t show for a scheduled talk. Instead, Kotick appeared, talking about Activision’s strategy for fostering talented studios to produce great games. [photo: Elisabeth Caren].

If game developers want to get resources and support to make their huge games, they should come to Activision Blizzard, he said. During the talk, Kotick insisted that his company is respectful of creative talent and it appreciates what the studios — where many founders remain — had done for the mothership. But he added, “If you want to sell out and move on, there are a lot of other companies to go to.”

He added, “Some ego is healthy, but outsized egos should be checked at the door. As Hillary Clinton says, it takes a village to make a game. If you think you can do it all by yourself, you’re probably the village idiot.”

Activision’s legal investigation into Infinity Ward’s alleged “insubordination” and “breach of contract” continued. Activision lawyers grilled Zampella and West in a windowless room for six hours on President’s Day. They interviewed other Infinity Ward employees. The attorneys were allegedly seeking information about attempts by the founders to contact Electronic Arts and other potential competitors.

Infinity Ward’s lawsuit says this was simply an attempt to “manufacture a basis to fire West and Zampella.” Activision Blizzard lawyers had demanded that the founders surrender their cell phones, PCs and other communications devices. When they refused on privacy grounds, the lawyers asserted that this was an additional act of insubordination. The company fired them on March 1.

West and Zampella sued Activision Blizzard’s Activision Publishing division on March 3, saying that the company was trying to get out of paying them $36 million.

“Activision has refused to honor the terms of its agreements and is intentionally flouting the fundamental public policy of this State (California) that employers must pay their employees what they have rightfully earned,” said their attorney Robert Schwartz, in a statement. “Instead of thanking, lauding, or just plain paying Jason and Vince for giving Activision the most successful entertainment product ever offered to the public, last month Activision hired lawyers to conduct a pretextual ‘investigation’ into unstated and unsubstantiated charges of ‘insubordination’ and ‘breach of fiduciary duty,’ which then became the grounds for their termination on Monday, March 1st.”

“We were shocked by Activision’s decision to terminate our contract,” said West in a statement. “We poured our heart and soul into that company, building not only a world class development studio, but assembling a team we’ve been proud to work with for nearly a decade. We think the work we’ve done speaks for itself.”

Zampella added, “After all we have given to Activision, we shouldn’t have to sue to get paid.”

Activision Blizzard then announced it had formed a new studio to take over the Call of Duty franchise, headed by Activision veteran Philip Earl. Zampella and West say they learned that Activision Blizzard had long been in preparations to replace Infinity Ward. It is interesting in hindsight that Activision Blizzard vacillated during 2009 about whether to call the new game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 or just Modern Warfare 2. Yet West and Zampella say that their employment agreement says they have control over the Modern Warfare name and any use of their game technology.

Activision Blizzard expects to release a new Call of Duty game from Treyarch this fall. In addition, Infinity Ward is in development on the first two downloadable map packs for Modern Warfare 2 multiplayer combat, for release in 2010. (Will those be released on time? That’s anybody’s guess). Activision Blizzard is in discussions with partners in Asia who could bring the franchise to online games in that region.

Activision Blizzard is announcing that a new game in the Call of Duty series is expected to be released in 2011 and that Sledgehammer Games, a newly formed, wholly owned studio, is in development of a Call of Duty game that will extend the franchise into the action-adventure genre. Sledgehammer is headed by industry veterans Glen A. Schofield and Michael Condrey. The pair previously created the DeadSpace shooting game for Electronic Arts.

In a statement, Activision Blizzard said, “Activision is disappointed that Mr. Zampella and Mr. West have chosen to file a lawsuit, and believes their claims are meritless. Over eight years, Activision shareholders provided these executives with the capital they needed to start Infinity Ward, as well as the financial support, resources and creative independence that helped them flourish and achieve enormous professional success and personal wealth. In return, Activision legitimately expected them to honor their obligations to Activision, just like any other executives who hold positions of trust in the company. While the company showed enormous patience, it firmly believes that its decision was justified based on their course of conduct and actions. Activision remains committed to the Call of Duty franchise, which it owns, and will continue to produce exciting and innovative games for its millions of fans.”

Electronic Arts, meanwhile, has announced that it will launch a new version of Medal of Honor game, set in in the modern combat era in Afghanistan, this fall. That leads us to where we are today. It sounds all too typical a story, with founders being pushed out of their company, developers squaring off against their publisher for the sake of independence and compensation, and lots of litigation ahead before the truth materializes, if ever.

Electronic Arts, meanwhile, has announced that it will launch a new version of Medal of Honor game, set in in the modern combat era in Afghanistan, this fall. That leads us to where we are today. It sounds all too typical a story, with founders being pushed out of their company, developers squaring off against their publisher for the sake of independence and compensation, and lots of litigation ahead before the truth materializes, if ever.

It’s truly sad, as I have never loved a video game franchise as much as this one. I have to believe that Zampella and West will form their own company and come up with something spectacular that makes Activision rue the day it didn’t pay them $36 million. Already, Kotick will now have a tough time convincing other independent studios that his parent company is kind and gentle enough to give them a fair deal and share the wealth that their games generate.

It’s ugly all the way around. And if it means that there will be delays in the launch of new Call of Duty or Modern Warfare games, fans will lose.

The topic of the building a blockbuster franchise will come up at GamesBeat@GDC inside the Game Developers Conference in the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco. Note: Online registration for the conference on Wednesday is closed but you can still register on site. Monday onsite registration is 5-7 pm. On Tuesday and Wednesday, on-site registration is open all day. Reminder: A press pass for GDC or an All-Access Pass for GDC can get you into GamesBeat@GDC. You can also get a GamesBeat only pass by registering on site.

The topic of the building a blockbuster franchise will come up at GamesBeat@GDC inside the Game Developers Conference in the Moscone Convention Center in San Francisco. Note: Online registration for the conference on Wednesday is closed but you can still register on site. Monday onsite registration is 5-7 pm. On Tuesday and Wednesday, on-site registration is open all day. Reminder: A press pass for GDC or an All-Access Pass for GDC can get you into GamesBeat@GDC. You can also get a GamesBeat only pass by registering on site.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More