When Apple bought chip design firm PA Semi in 2008, it seemed like a crazy move. Who’d want to go back to the days when giants like IBM did everything themselves, including making software, hardware and chips? Now, in the age of smartphones and tablet computers, Apple has what it needs to control its own destiny. It’s starting to look crazy like a fox. And rivals like Google are following Apple’s lead.

When Apple bought chip design firm PA Semi in 2008, it seemed like a crazy move. Who’d want to go back to the days when giants like IBM did everything themselves, including making software, hardware and chips? Now, in the age of smartphones and tablet computers, Apple has what it needs to control its own destiny. It’s starting to look crazy like a fox. And rivals like Google are following Apple’s lead.

“Apple is the new IBM, and everyone wants to be like Apple,” said Rob Enderle, an analyst at the Enderle Group.

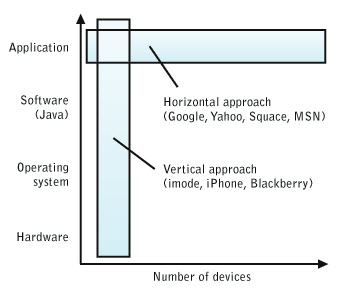

The strategy is called vertical integration, and it’s hot again in Silicon Valley. Technology giants that once focused on software or Web services — one horizontal layer of the technology stack — are now acquiring chip designers in order to differentiate themselves from the pack and disrupt their competitors.

Tech’s vertical past

In the beginning of the tech industry, companies like Digital Equipment Corp. and IBM had vertical business models. They designed everything they needed to make products: operating systems, applications, hardware, chips, services, and brands. It was all internal.

The pendulum swung against this model in the 1980s. Along came Microsoft and Intel, which tooks slices of what IBM did and concentrated all of their energy on doing them better. With their operating systems and chips, they disintermediated IBM, giving rise to PC clone makers and creating new horizontal industries.

The pendulum swung against this model in the 1980s. Along came Microsoft and Intel, which tooks slices of what IBM did and concentrated all of their energy on doing them better. With their operating systems and chips, they disintermediated IBM, giving rise to PC clone makers and creating new horizontal industries.

For a time, the horizontal integration of the tech industry drove the creation of new startups and billion-dollar companies. Venture-backed Compaq thrived in this era.

And it wasn’t just PCs. Intel no longer needed to build its own chipmaking equipment; it relied on Applied Materials. And it no longer needed to write its own chip-design software, relying instead on the likes of Synopsys and Cadence. Seagate made better hard drives than IBM, and IBM eventually gave up that business. Taiwanese contract chip makers offloaded the process of making chips, allowing Intel’s competitors such as Nvidia to focus on designing them.

Back in style

But given the behavior of today’s tech giants, it looks like the old IBM had the right idea. With today’s acquisitions, we see the pendulum moving back. The reason this is happening is the potential for disruption. When the technology industry is undergoing a big shift, a shift from horizontal to vertical can shake up the competition.

In the present moment, with the rise of mobile devices, having access to chip technology that can differentiate products in the market is a vertical move that can make all the difference.

“At the end of the day, all of those vertical businesses require silicon,” said Anand Chandrasekher, senior vice president and general manager of the Ultra Mobility Group at Intel. “And silicon makes the world go around. This is all happening now because there is so much opportunity.”

Apple has been executing the old IBM model for some time. It had always made its own operating systems and hardware, but relied first on its PowerPC partnership with IBM and Motorola and later Intel for its PC microprocessors. With the new iPods and iPhones, it moved toward ARM-based chips which could be created by a larger variety of suppliers. Apple also moved to Asian hardware makers such as Foxconn to assemble its devices, allowing Apple to focus on design and marketing.

But it was galling to Apple that chip designers could have chips fabricated for $10 and sell them to Apple for $30. And it also needed better performance and battery life in upcoming devices like the iPad. So, in addition to PA Semi, Apple has purchased another chip design company, Intrinsity, to allow it to design its own ARM-based chips for the iPad and future iPhones.

Against that background, rumors that Apple would buy ARM for $8 billion — a ludicrous prospect just a couple of years ago — are still crazy, but maybe not that crazy. But Apple doesn’t need ARM to pull off its vertical strategy. Apple has plenty of cash and is in a race to buy lots of other companies as it tries to outmaneuver Google. One recent example: Quattro Wireless, a mobile-advertising concern which puts Apple in a business no one expected it to play in even three years ago. If Apple bought ARM in order to keep that company from arming Apple’s rivals, then the only point of that acquisition would be to engage in anti-competitive behavior.

Who is copying who?

Google tried to take on Apple’s iPhone with the Android mobile operating system. But early results were tepid with third-party vendors who created Android-powered phones under their own brands. Google then designed and sold its own phone, the Nexus One, which didn’t fare much better. Now, perhaps in the hopes of matching Apple, Google has acquired the startup Agnilux, which was started by some of the same people who created chips for PA Semi.

Microsoft had a lesson in the value of going vertical some time ago. It bought WebTV back in 1997, acquiring a team of hardware and chip designers. It used some of those experts to create the original Xbox game console in 2001, allowing it to enter the console business and disrupt both Sony and Nintendo, who were threatening Microsoft’s hold on home consumers. (Microsoft tried without success to get PC makers like Dell to manufacture the Xbox in a horizontal strategy.) Since Sony and Nintendo weren’t customers for Microsoft’s Windows operating system, that vertical move didn’t do Microsoft any harm. Then, with the Xbox 360, Microsoft brought more of the chip design under its control. It hired ATI Technologies and IBM to create custom chips, not generic ones like those used in the Xbox. That enabled Microsoft’s Xbox 360 to compete on a better footing against Sony’s fully custom, internally designed PlayStation 3.

Microsoft had a lesson in the value of going vertical some time ago. It bought WebTV back in 1997, acquiring a team of hardware and chip designers. It used some of those experts to create the original Xbox game console in 2001, allowing it to enter the console business and disrupt both Sony and Nintendo, who were threatening Microsoft’s hold on home consumers. (Microsoft tried without success to get PC makers like Dell to manufacture the Xbox in a horizontal strategy.) Since Sony and Nintendo weren’t customers for Microsoft’s Windows operating system, that vertical move didn’t do Microsoft any harm. Then, with the Xbox 360, Microsoft brought more of the chip design under its control. It hired ATI Technologies and IBM to create custom chips, not generic ones like those used in the Xbox. That enabled Microsoft’s Xbox 360 to compete on a better footing against Sony’s fully custom, internally designed PlayStation 3.

A far trickier shift came in 2008 when Microsoft bought Danger, a designer of early smartphones like the Sidekick, to build its new Kin line of smartphones for teens. That vertical move arguably hurt its horizontal strategy of pushing its Windows Mobile operating system, as Microsoft started competing with its own partners in phones.

Intel has also moved down the vertical road. The world’s biggest chipmaker bought Wind River Systems for $884 million in 2009 to acquire its own embedded operating system. Wind River’s software runs on everything from cars to industrial controls. To spread its chips far beyond the PC, it made sense to Intel to buy Wind River. The full impact of that move hasn’t been played out yet.

It works the other way too

Moving from a different starting place, database giant Oracle decided that vertical integration was a great way to sell more software. So it bought hardware maker Sun Microsystems for $7 billion last year. We have yet to see whether that was a wise move or not. But through Sun’s Sparc architecture, Oracle now owns a big team of chip designers. And, in contrast to early expectations, Oracle hasn’t dismantled the chip design teams that it acquired from Sun. Who would have thought that Larry Ellison would be a semiconductor guy?

Hewlett-Packard also has not been content relying on others for its operating systems. With the $1.2 billion acquisition of Palm announced last week, HP didn’t just pick up a smartphone-design operation. It also acquired the WebOS operating system, which can be used in anything portable, from tablet computers to smartphones. No longer is HP dependent on Microsoft’s Windows for the software to run on its so-called slate computer, which is likely being redesigned.

The pendulum swing

The irony is, of course, that IBM has shed much of its vertical business model. It sold off its old PC division to China’s Lenovo in 2004. IBM still makes chips and software, but its mainstay business is services, a business which gathers the best offerings of the horizontal players and packages them for its customers. In the meantime, HP has surpassed IBM as the world’s biggest computer company.

The irony is, of course, that IBM has shed much of its vertical business model. It sold off its old PC division to China’s Lenovo in 2004. IBM still makes chips and software, but its mainstay business is services, a business which gathers the best offerings of the horizontal players and packages them for its customers. In the meantime, HP has surpassed IBM as the world’s biggest computer company.

The lesson isn’t that vertical beats horizontal. These cycles move in a pendulum, and success depends on how well each company executes as the industry swings.

What’s crucial that companies find the right strategy and the right level of integration. Going vertical for the sake of going vertical isn’t the point. Companies need to know what they have to own in order to control their own destinies, and what they should buy from someone else because that someone else makes it better.

What moves the pendulum?

It helps to time the disruptions correctly. The cycles of vertical vs. horizontal are usually aligned with a major change in the tech industry. As the PC era arrived, horizontal integration enabled Compaq Computer to clone the IBM PC and disrupt the vertical computer industry. Dell disrupted Compaq when selling directly over the Web became viable. With the arrival of smartphones, Apple managed to disrupt the companies that focused on phone hardware, such as Motorola or Nokia. With tablets, the opportunity to shake things up again is here.

These disruption strategies are sure to continue, with more multibillion-dollar acquisitions in the offing. Companies are flush with cash and they’re in a race in a kind of grand chess game to beat their opponents.

The next swing

The companies with the big cash hoards — Google, Microsoft, Apple, Intel, HP, IBM and Oracle — are increasingly likely to deploy them — as long as they don’t overreach and attract the attention of the government’s antitrust cops.

Entrepreneurs could position themselves to take advantage of this trend by creating startups likely to be acquired by those seeking to become vertical. But that’s usually not a strategy you can bank on. Smaller companies should also look upstream and downstream to figure out whether key customers or suppliers might be acquired.

It’s fun to speculate what could happen next in this vertical moment: What would happen if Apple bought Nvidia? Or if HP bought Advanced Micro Devices? Or if Nintendo bought Broadcom? Or if Facebook bought Zynga? It would be a different world.

Offer your own predictions in the comments, and please take our poll below.

[art credits: Wikipedia, Zabong, 2012forum]

Do you think vertical integration or horizontal integration is the better strategy?Market Research

Don’t miss MobileBeat 2010, VentureBeat’s conference on the future of mobile. The theme: “The year of the superphone and who will profit.” Now expanded to two days, MobileBeat 2010 will take place on July 12-13 at The Palace Hotel in San Francisco. Early-bird pricing is available until May 15. For complete conference details, or to apply for the MobileBeat Startup Competition, click here.