A teenage prank on Twitter turned into the hack heard round the world Tuesday — and VentureBeat now has the story behind it. Through an exclusive interview with the two New Zealand kids whose code spread around the world in minutes, we learned exactly how idle mischief from down under turned the fast-growing microblogging site upside-down.

A teenage prank on Twitter turned into the hack heard round the world Tuesday — and VentureBeat now has the story behind it. Through an exclusive interview with the two New Zealand kids whose code spread around the world in minutes, we learned exactly how idle mischief from down under turned the fast-growing microblogging site upside-down.

The incident raised questions about Twitter’s security. The site has swiftly grown to more than 140 million users. It recently raised $100 million in venture capital and is valued by its investors at more than $1 billion. It has gone on a hiring spree, even as many question its plans to make money. And the fact that two teens were so easily able to take it over raises the concern that it’s neglecting security amid its torrid growth.

The hack first spread through an account named @Matsta, who resides in Auckland, New Zealand, the city where I live. I got in touch with Matt, the 17-year-old behind that Twitter handle, to find out the real story.

Matt and his friend Harrison, both high school students, admited that they were involved in spreading the exploitative code. (Both are 17, so VentureBeat is not publishing their last names.) Drawing from our exclusive interview with the pair, who have both blogged about the incident, we now have the story behind the Great Twitter Exploit of 2010.

The hack used well-known security flaws in JavaScript, a simple programming language used extensively in websites, to take over the accounts of Twitter users when they visited the service’s website. Users rolling their mouse over certain pages and links automatically retransmitted malicious code, messages, and links to their followers — the mechanism by which the Twitter worm swiftly spread. Twitter fixed the exploit later Tuesday morning.

The story began when a developer in Japan, known as @kinugawamasato on Twitter, found a vulunerability in Twitter’s code. The exploit, a version of a commonly known hacking technique called cross-site scripting (XSS), enabled custom JavaScript code to be executed whenever a user’s cursor paused over a link. The developer reportedly made Twitter aware about the issue a month ago. Company representatives reportedly responded by telling him they’d fixed it. (According to a Twitter corporate blog post, they had addressed the issue, but subsequently rolled out code that restored the vulnerability.) The Japanese hacker, noticing that the vulnerability remained, went on to create a harmless Twitter profile that changed the background colors of his tweets to different colors as a proof of concept.

The exploit was seen by a 17-year old Australian teenager named Pearce, who goes by @zzap on Twitter. Pearce modified the exploit to enable it to insert JavaScript in a tweet. This version of the exploit, which he posted on Twitter, displayed the words “uh oh” whenever a user rolled their mouse over a link.

The exploit was seen by a 17-year old Australian teenager named Pearce, who goes by @zzap on Twitter. Pearce modified the exploit to enable it to insert JavaScript in a tweet. This version of the exploit, which he posted on Twitter, displayed the words “uh oh” whenever a user rolled their mouse over a link.

One of Pearce’ followers on Twitter was Harrison, a friend of Matt’s, who goes by @Peppery on Twitter. Harrison noticed the code in the hack was too long for it to run any “meaningful” JavaScript code, given Twitter’s 140-character limit on posts. He went on to shorten the code to a fourth of its original size, and found a way to make it automatically retweet a message by having the entire page — not just a single link — react on the movement of the cursor. That improvement proved key to spreading the hostile code.

“When you can make something retweet itself, you have what is essentially the same thing as the Samy XSS worm that propagated on MySpace some years ago — a virally spreading exploit,” Harrison pointed out.

Having laid the groundwork for a successful exploit, Harrison then instant-messaged the code to his friend, Matt (@Matsta), as a joke. “Go to Twitter and copy and paste this into the box,” he said in a message, pointing to the code he had just come up with.

Having laid the groundwork for a successful exploit, Harrison then instant-messaged the code to his friend, Matt (@Matsta), as a joke. “Go to Twitter and copy and paste this into the box,” he said in a message, pointing to the code he had just come up with.

“When I sent it his way, I was mostly curious as to what would happen when the code was posted,” Harrison says.

Matt, who said he was unaware of what the code would do, tweeted it out to his 800 people who subscribed to him on Twitter, and thus was born the infamous Twitter exploit.

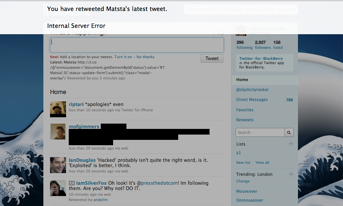

Now it’s no secret what took place afterwards. In just over two minutes, the exploit had been retweeted thousands of times, spreading from user to user as they opened their Twitter homepages and saw someone’s tweet.

Jonathan George, the developer of Boxcar, a popular iPhone application which sends Twitter notifications to a phone, noted that one of Matt’s tweets had been retweeted 61,516 times. Needless to say, within minutes, the word “Matsta” was trending on Twitter.

Soon after, spammers and other miscreants took notice and modified the code for their own use, spreading links to pornographic sites and opening up malicious popup windows. What started as some idle fun to see how Twitter would handle self-propagating JavaScript code turned into a viral spam heaven, with links being spread by the the mere opening of the Twitter homepage.

“We had no idea that it would take off in that way,” said Matt. “I only gave it two seconds of thought before I posted the code.”

Around 7 a.m. Pacific Time, Twitter suspended Matt’s Twitter account, apparently in response to the hacking incident.

Around 7 a.m. Pacific Time, Twitter suspended Matt’s Twitter account, apparently in response to the hacking incident.

However, the code was still out and being retweeted until Twitter developers finally fixed the underlying vulnerability at around 9 a.m. Pacific Time. Meanwhile, back in New Zealand, where it was already night, Matt and Harrison headed to bed to get ready for class the next morning.

The news caught fire as they slept. The story was covered by nearly every major outlet around the world. To date, there are over 1,800 news stories containing the word “Matsta”, according to Google News. Back at home, the New Zealand Herald reported the involvement of two fellow Kiwis in the attack, as did a national TV news channel.

As a result, Matt and Harrison’s Facebook pages have since been littered with links to coverage of the incident, with friends and acquaintances congratulating the two for making world news with an idle prank.

Matt has since made a new Twitter profile and hopes the company will let this one slide. “No, I will not hack your Twitter,” he promises in his bio. (Update: it appears Matt’s new account has also been suspended by Twitter. Update 2: Twitter is working with Matt to restore his account, on the promise that he will “report this kind of stuff responsibly before letting it spread.”)

Carolyn Penner, a Twitter spokesperson, said the company would not pursue legal action against either Matt or Harrison.

[Homepage photo: bixentro]

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More