This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Sir-tech: The Old Standard

1979 – 2003

The road to the first Wizardry didn't start with a role-playing game or in someone's basement. It started with a mailing list.

It was the late seventies, and would-be dungeon master Robert Woodhead was busy developing a mailing program to help his mother's novelty business. With the help of partner Fred Sirotek, Jr., who had also bankrolled a $7,000 Apple computer, Woodhead created Infotree. Always the entrepreneur like his father, Sirotek saw the dollar signs that Infotree could bring in.

Taking the project and the expensive Apple to the Trenton Computer Show, Fred's brother, Norm, drove Woodhead on the road trip from Canada. After seeing the enthusiastic response that a mailing list had created with the crowds, they came back with a new idea.

Norm knew an opportunity when he saw it. If people were that excited over a piece of business software, how would they react to a game?

A space-based wargame, Galactic Attack, was the next project, said to have been dreamt up during the drive back home from the show (though a vague Wikipedia entry doubts this story by saying that it was adapted from another early PC game: 1973's Empire). After convincing Fred Sirotek, Sr. to part with the capital to get the project started, Infotree completed Galactic Attack and sold enough to fund the next one — and the company that would bring it to the world: Sir-tech. It was a game that Woodhead had been playing at Cornell with fellow student Andrew Greenberg: Dungeons of Despair.

Dungeons of Despair had a rough coming-out party in '81 when the legendary Gary Gygax, then chairman of TSR, threatened to litigate against it if only because of its “double d” title. That litigation apparently never went through, but Dungeons of Despair did change its name to one that RPG fans of the classics the world over will forever recognize: Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord. It would become one of the defining CRPGs — not only for its time but for the genre as a whole — and be the start of a long series that would include Brenda Brathwaite's 18-year career in the industry and D. W. Bradley's run during with the fifth, sixth, and seventh installments.

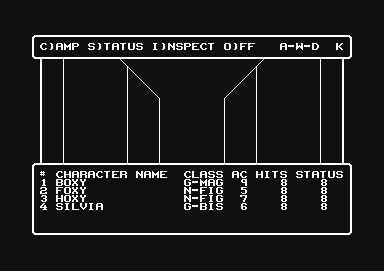

Wizardry took a decidedly different direction than Ultima did with its exclusively first-person view of wireframe corridors, colorful monster graphics, and in allowing the player to custom build a party of characters. But the investment that players had in molding their own characters was also a significant factor for the series at the time.

Being able to choose from several classes and races to create a team with which to smash monsters spoke to the D&D roots that more than a few CRPGs at the time aspired to emulate. Although Ultima 3 would bridge the gap in '83 with non-player characters who could join the player's party, Wizardry was already there. This inspired many others to follow their example, such as in Japan where both Wizardry and Ultima proved to be influential references for its budding CRPG and console markets…such as with Enix's Dragon Warrior.

The first three games were also notoriously hard on players and scaled in difficulty, which offered an import function for characters as they went from title to title. Jumping into the third game without playing any of the previous ones would almost guarantee hours of frustration similar to missing an episode of Lost. And when the entire party died in Wizardry, it was dead permanently: the player was forced to start all over again with a fresh batch. But thanks to another innovative twist, this new party could also find the bodies of the slain party and bring them back.

Wizardry's wireframe corridors were reminiscent of Richard Garriott's work in Akalabeth and later in Ultima, but the difference here was that you now had multiple classes and a party to work with. It was like walking into a dungeon with multiple personalities. Each one armed with sharp objects.

This hardcore approach to CRPGs was arguably at odds against Ultima's slightly more accessible direction. As revolutionary as its features were, the difficulty and frustration of the series had also attained a sort of mythic status that is still well regarded today by its longtime fans. The design of the fourth Wizardry even solicited save disks from players of the previous entries in the series in order to turn their characters into enemies for the player to fight past as an evil wizard. Yes, you were the bad guy in Wizardry 4 and these do-gooders — who might even have been your own party at one time — were your worst nightmare as you fought your way to one of the game's multiple endings.

As a first for CRPGs, or gaming in general, the boxes were even stamped with warnings advising at what skill level a player should be at with a particular title. Imagine a game like Final Fantasy 13 stamped with the warning “Experts Level: Previous Final Fantasy experience required!” But that didn't stop the series from receiving accolades from all walks of life: even from a psychologist who wrote in to tell the developers that he had used the first game as a tool in helping to reach a troubled child contemplating suicide.

Sir-tech was also a publisher renowned for titles such the tactical Jagged Alliance series, and imports such as the Realms of Arkania, but Wizardry was what it was best known for. While not as prolific as Interplay or Origin, its low-key profile and consistent attention to quality guaranteed that nearly every Wizardry title would continue to amaze its fans.

The later games would up the ante on devious riddles, traps, and dungeons filled with the additional wrinkle of interacting with NPCs via a text parser to bring greater depth to interactions. The series continued to evolve with Wizardry 5's "odd man out" entry which set the pace for gameplay improvements through the next three titles.

Wizardrys 6 through 8 would prove to be among the series's finest hours by raising the bar on player character development and dungeon crawling packed into a storyline that blended together sci-fi hints, high fantasy, and tongue-in-cheek humor. An advanced parser system, deeper character builds and a developing skill system provided players with even more directions in which to experience the series's evolving gameplay.

Unfortunately, unlike Interplay and Origin, its track record wasn't as good when it came to publishing or diversity. Eventually, it wasn't enough to keep its original publishing arm open — the one responsible for releasing the original Wizardry — and which the name “Sir-tech” had been most identified with.

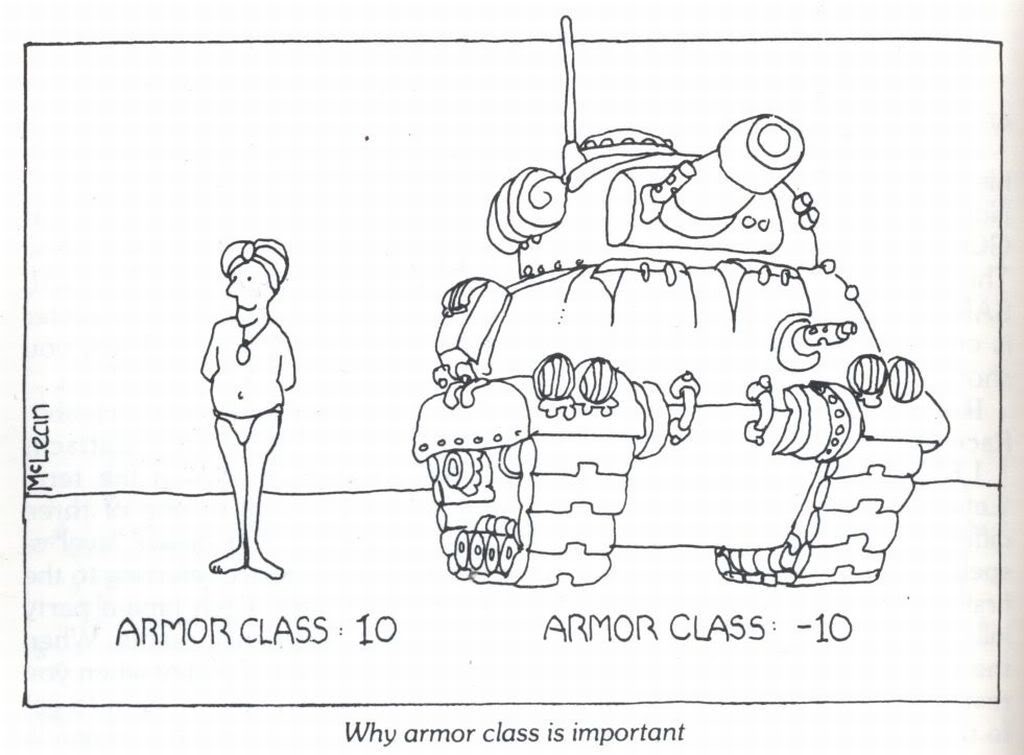

The manual authors had a nice sense of humor in explaining the nuances of Wizardry. The game, on the other hand, was all business — deadly, crying-over-floppies-filled-with-dead-characters business.

Sir-tech eventually shuttered its doors in '98 under unclear circumstances, though money and a changing retail model were hinted at as factors. Sir-tech Canada, a separate entity from the publishing side of the company, continued on to finish Jagged Alliance 2 (released in 2000) and Wizardry 8 (released in 2001) before folding in 2003.

But that's not the end of the Wizardry story.

I mentioned before that Wizardry and Ultima were incredibly popular in Japan and had a huge influence on its then-young CRPG and console markets which inspired early pioneers such as Dragon Warrior's Yuji Horii. But I had no idea just how popular.

When it first came to Japan in the eighties, Wizardry had also inspired a media blitz across print and video that left a huge impression on the RPG audience. Not only did its phenomenon reach across media channels in Japan back in the day, the series continues on with a list of spin-offs and original productions catering to a dedicated fanbase.

Wizardry the anime is really out there. And yes, there really is a ninja class in the game.

The first Wizardrys would even be remade years later for the Famicom and other systems, such as the PC Engine, complete with improved visuals. Even the PS2 would get its own Wizardry titles, though only one or two of these would ever find their way over to the West (thanks to Atlus), such as Wizardry: Tales of the Forsaken Land in '01. After the original Sir-tech had closed its doors, Wizardry lives on. Or at least the rights do, now owned by an obscure company called IPM, Inc. in Japan.

As for the original programmers that started this whole craze in the first place, Robert Woodhead is currently enjoying life as well as running Animeigo when he's not ruling over the masses as an evil overlord (Trebor is the name of the Mad Overlord from the first Wizardry). His partner in crime, Andrew Greenberg, has put aside his role as an evil wizard (Werdna from the first and fourth Wizardry) to practice law instead. And longtime Wizardry designer, Brenda Brathwaite, is still around today, having contributed to many other titles such as Jagged Alliance as well as having helped to teach a new generation of designers and would-be game developers the ropes — before returning to game development.

Check back in two weeks for Interplay: From Bards to Bombshells. See page two for further reading.

Further reading:

IGN Staff, "Sir-tech's Last Words." IGN. October, 1998

McClatchie, Joanna, "Interview on Women, Games and Design." Applied Game Design. January 7, 2009.

Parish, Jeremy, "8-Bit Cafe: Big in Japan." 1UP. March 3rd, 2009.

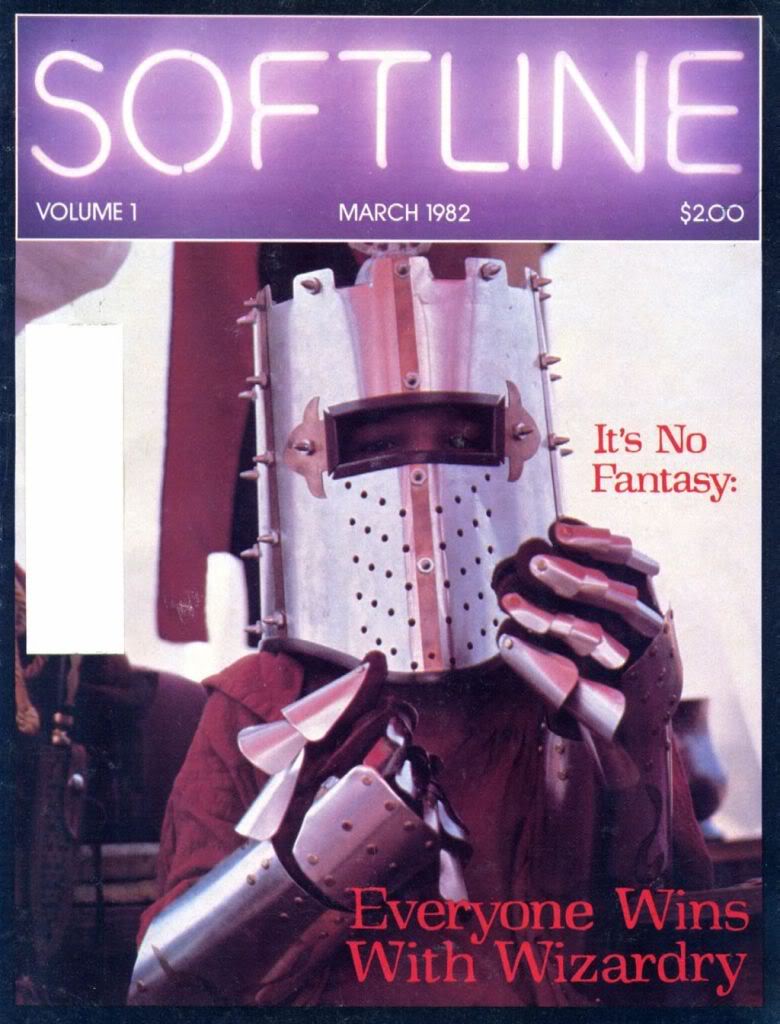

Adams III, Roe R., “Come Cast a Spell with Me: Plumbing the Depths of the Wizardry Phenomenon.” Softline. March, 1982, p. 32.

Lee, Wyatt “A Foreshadowing of Fantasy Jewels in a Duel Arcane: Ultima V and Wizardry IV.” Computer Gaming World. October, 1987, p. 16.

Scorpia, “Computer Role-Playing Games: Now and Beyond.” Computer Gaming World. June-July, 1987, p. 29.

Wilson, Johnny L. “Company Report: Wizardry's Family Infotree – Turning a House of Sand into a Castle of Silicon.” Computer Gaming World. December, 1992, p. 192.