SoundCloud may be the biggest music startup you’ve never heard of.

SoundCloud may be the biggest music startup you’ve never heard of.

It’s a large-scale platform for people to share the sounds they create and has quietly conquered the professional music community, amassed 4 million users and expanded into all kinds of sound, from podcasts and public earnings calls to cat impersonations. We covered the Berlin-based startup back in 2009 when it pulled in over $3M in funding, but it’s been mostly under the radar since then.

I recently talked to CEO and co-founder Alexander Ljung about how sound will become the sixth sense of the social graph. “We want to unmute the web,” said Ljung. “We think the web is very silent at the moment.”

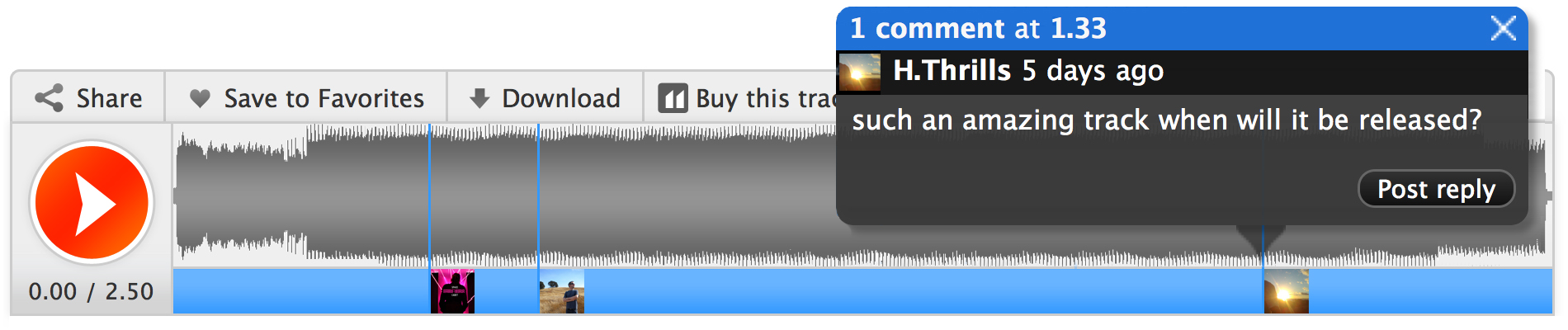

SoundCloud started off as a way for Ljung and his co-founder Eric Wahlforss to share a piece of music with someone privately and get feedback. This led to the SoundCloud waveform; a visual representation that allows listeners to add comments at any point in the recording.

“We both came from the creator side of music. Eric was an artist creating music. I worked as a sound designer creating sounds and music for TV and films. We had both been tech geeks all our lives and were really into the whole social web movement around the time of Flickr. But there was no Flickr for music. There was nothing built for artists.”

SoundCloud had an API from the beginning so that developers could build various apps of their own on the platform. It now has around 150 apps. I asked Ljung about some of his favorites. “I made some beats on the Gorillaz beatbox app (for iPad) this weekend and then 50 Cent put up a vocal track where it’s only him rapping and he asked people to produce it. So now I have a track that I produced for 50 Cent!”. The Berkley school of music, one of the premier music schools in the world, recently rebuilt its environment to run its online courses entirely from SoundCloud.

SoundCloud had an API from the beginning so that developers could build various apps of their own on the platform. It now has around 150 apps. I asked Ljung about some of his favorites. “I made some beats on the Gorillaz beatbox app (for iPad) this weekend and then 50 Cent put up a vocal track where it’s only him rapping and he asked people to produce it. So now I have a track that I produced for 50 Cent!”. The Berkley school of music, one of the premier music schools in the world, recently rebuilt its environment to run its online courses entirely from SoundCloud.

Initially, SoundCloud was a set of tools for professional and semi-professional music creators. It’s now the standard way for many DJs and music makers to send and receive music. But Ljung soon noticed that people were using the platform in other ways too. “We saw how people were using SoundCloud for podcasts, radio interviews, sound effects. It started to dawn on us that the distinction between sound and music is fake. Music is one genre of sound, but there are many others.”

Ljung points out that many services now make it easy to create and capture sounds. “If you think of Twitter, it’s the simplest thing you can imagine. 140 characters. Even a sentence is an object.” Combine this simplicity and granularity with the emotional impact of sound and you get something special.

“If you want to stop being scared when watching a horror movie, you mute the sound. Sound is the emotional carrier,” Ljung told me. Human beings derive richer layers of meaning from a voice than from a written sentence. The background sounds when you call someone give them an instant impression of your situation. So why not do status updates in sound? Ljung calls these “social sounds”. SoundCloud has a variety of mobile apps to capture and share sound anywhere and anyplace.

This is part of the thinking behind one of SoundCloud’s latest services. “Last week we launched a service called TakesQuestions. You can record a question for me and I will record an answer. It’s like this asynchronous conversation. Somebody from the X-factor in the UK is doing it for instance,” Ljung said.

SoundCloud doesn’t seem to have any direct competitors. Like Flickr, its business model is based on a hierarchy of accounts from free to premium. The company opened an office in San Francisco recently, and Ljung now splits his time between the U.S. and SoundCloud’s headquarters in Berlin. Union Square Ventures invested $10 million in SoundCloud in 2010.

I asked Ljung for his thoughts on the future of the music business.“The general discussion is still that the music industry is in so much trouble, which is really not true. There are more people today than ever before who are involved in creating music. It’s time for a different definition of what the music industry is. The musical instrument market is twice as large as the recorded music market, and that’s been stable for 30 years. You need to look at what people are actually spending on engaging with music, not just listening to it. A guitar costs $1,000 or $1,500. That’s a lot of iTunes tracks.” Amen to that.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More