Steven Levy wrote his first book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, in 1984. At the Defcon hacker conference in Las Vegas today, he talked about the word “hacker” and its origins amid a crowd of young practitioners of the craft, many of whom weren’t born when he published that book.

Steven Levy wrote his first book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, in 1984. At the Defcon hacker conference in Las Vegas today, he talked about the word “hacker” and its origins amid a crowd of young practitioners of the craft, many of whom weren’t born when he published that book.

Levy said that over the years, the word “hacker” became corrupted to mean people with pimples who were getting into trouble with the law because of the crimes they committed with their computers. But Levy’s talk was entitled, “We owe it all to the Hackers.”

Levy was a writer for Rolling Stone magazine and was assigned to write a story about hackers, who had been painted as sick computer addicts, pimply faced kids, and miscreants in early reports. But Levy found a vibrant community growing up in Silicon Valley, Seattle, and Cambridge, Mass. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, and the early computing community at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology all shared a common set of views about hacking that Levy called The Hacker Ethic in his book. They were a bunch of wizards trying to do something clever and impossible.

“They were like adventurers, thrilled with the computer,” Levy said.

All of these people were inspired by the personal computer. Levy interviewed Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, about why he enjoyed tinkering with computers during the early days of the Homebrew Computer Club in Silicon Valley. Levy got into a heated discussion about the meaning of the word “antitrust” with Bill Gates, who became so angry that he threw a pencil at Levy. But the common view of hacking, at its core, was a belief that “information should be free,” Levy said. Stewart Brand, a computing pioneer, created his own hacker conference and hacked that idea, saying, “information wants to be free.”

All of these people were inspired by the personal computer. Levy interviewed Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple, about why he enjoyed tinkering with computers during the early days of the Homebrew Computer Club in Silicon Valley. Levy got into a heated discussion about the meaning of the word “antitrust” with Bill Gates, who became so angry that he threw a pencil at Levy. But the common view of hacking, at its core, was a belief that “information should be free,” Levy said. Stewart Brand, a computing pioneer, created his own hacker conference and hacked that idea, saying, “information wants to be free.”

At MIT, Levy said there was more of a prankster nature to the hackers, who had a love for explosives. One administrator made peace with the hackers, who were constantly stealing things from the university. He told them to stop destroying things and start creating an “illusion of security.”

“That’s what companies do today, create an illusion of security,” Levy said.

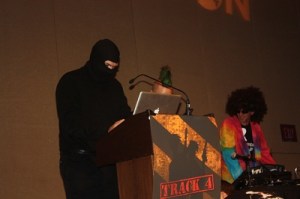

That spirit is still alive. Here at Defcon today, some prankster got into the wireless lighting system and was pulsing the lights on and off at the conference. Earlier in the week, someone pulled a fire alarm during the keynote speech at the sister conference, Black Hat, which is more academic and corporate than Defcon, which is free-spirited and a cash-only affair, as hackers don’t always like to give away their identities via credit cards. At Defcon, attendees are a more diverse group — with a lot of hipster clothing and multi-colored hair (yes, those are stereotypes as most people are dressed in jeans and T-shirts).

Levy said he interviewed a young guy, Richard Stallman, who was virtually living at MIT. Stallman eventually became the founder of the “free software” movement that led to things like Linux. As Levy spoke, lots of young people nodded their heads and appeared to smile as if they were hearing someone describe the roots of their religion.

Levy said he interviewed a young guy, Richard Stallman, who was virtually living at MIT. Stallman eventually became the founder of the “free software” movement that led to things like Linux. As Levy spoke, lots of young people nodded their heads and appeared to smile as if they were hearing someone describe the roots of their religion.

Levy said he was somewhat wary of what the outcome would be for hackers so many years later. He thought that commercialism would water down the hacker ethic and further corrupt its authenticity. But he said he was glad to see that he was wrong about that and that the computer revolution spread the ethics of hacking like a virus around the world, leading to things like the Macintosh, the free internet, open source software such as Linux, and companies such as Facebook and Google. Levy said that, on the 25th anniversary of the publication of the book, he interviewed Mark Zuckerberg, another famous hacker, who said that he wanted Facebook to be a “great hacker company.” That was like returning to the old meaning of the word.

Jeff Moss, the founder of Defcon (which is 19 years old now), told me that he invited Levy to speak to impart some wisdom about the ethics of hacking and the perspective of decades of experience. Moss said it was good for young people to learn. In fact, for the first time, Defcon features a section, dubbed Defcon Kids, for children ages 8 to 16, for the very first time. Defcon is a place where the meaning of hacker is understood, in the expansive and curious and hopeful sense. It is a place where the dark stereotype just isn’t big enough to capture everything that it’s about.

Levy said he is often asked why he never wrote a sequel to Hackers. But he said almost every book he has written has touched on the same topics, whether it’s a book about cryptography or his latest book, In the Plex, about Google.

Ironically, Levy said he had never been to a Defcon conference before. Just after he spoke, the conference started playing the movie “Hackers,” which had little to do with Levy’s book and stars Angelina Jolie. Levy joked that the impression people had of hackers was less of someone like the glamorous actress and more like the kind of luck-less people that she should adopt. Moss watched the film with the group and made comments about it, while the audience giggled at the archaic tech scenes.