Above: Brian Fargo

Double Fine Productions turned video game funding practices upside down last week when it raised more than $1.75 million through the crowd-funding site Kickstarter in record time. That money will go toward the development of a new adventure game that would otherwise never have been made.

Lack of funding has been putting a squeeze on a lot of mid-sized game development companies, but crowd-funding might turn that trend around.

“This could bring a wonderful dynamic change to our industry,” said Brian Fargo, chief executive of InXile Entertainment, in an interview. “It is a very exciting time to be a developer again.”

Fargo has been making games since the 1980s, first at Electronic Arts, then at his own company Interplay Productions, and now at InXile. He owns a variety of properties that are beloved by gamers who grew up with titles such as The Bard’s Tale. His only problem is that he doesn’t run a gigantic video game publisher.

He recently relaunched The Bard’s Tale — originally developed in 1985 and remade in 2004 — on the iPhone and saw an outpouring of appreciation from nostalgic fans. The game made it into the top 10 ranks on the App Store in December. A full remake of the game might be possible if Fargo can raise the money through crowd-funding sources.

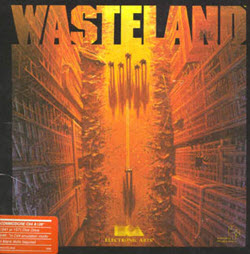

But before he takes on The Bard’s Tale again, Fargo is thinking of dusting off his game Wasteland and funding it through Kickstarter. He wants to hear more fan feedback before starting the funding process, but he is seriously contemplating raising money through the crowd-funding process.To do the game right, he would need more than $1 million.

“In almost every single interview I do, the game press asks me if I’ll ever do Wasteland again,” Fargo said.

The 1988 version of Wasteland was a post-apocalyptic role-playing game with large parties. After it came out, Interplay switched over to making Fallout games as single-player titles But Fargo has wanted to make an online multiplayer version of Wasteland for the Internet, where large parties can come together and play the game. For now, Fargo doesn’t think that Kickstarter is big enough to fund big-budget console games.

The 1988 version of Wasteland was a post-apocalyptic role-playing game with large parties. After it came out, Interplay switched over to making Fallout games as single-player titles But Fargo has wanted to make an online multiplayer version of Wasteland for the Internet, where large parties can come together and play the game. For now, Fargo doesn’t think that Kickstarter is big enough to fund big-budget console games.

Gamers might love a particular franchise so much that they will volunteer their own money to invest in the project. And the feedback that comes from something like Kickstarter could give a developer confidence that their game property has legs. If you try to raise money on Kickstarter and the project goes nowhere, that’s a pretty good indication that nobody wants to play that game.

InXile has a variety of properties that could use funding and 15 employees. Fargo shopped Wasteland around to publishers, but they were risk averse and really wanted to games that had a chance to rake in $1 billion in sales. If he does the project on his own, Fargo can make the game edgier, with a gritty world full of moral dilemmas for the players.

“The game industry has separated itself into the huge blockbuster companies and the independent developers in their garages,” Fargo said. “But it’s pretty hard to be in the middle. Is there any business model left standing for the mid-size developers?”

The important thing about crowd-funding is that it gives game companies in the middle an option that can preserve their creative freedom. Indie game developers might also turn to Kickstarter, but it could prove tough raising a ton of money for a game project if the developer is a relative unknown.

Sana Choudary, chief executive of the game startup accelerator YetiZen, said that she had tried crowd-funding with her accelerator’s startups and had a harder time raising money that way than through a conventional investing or publishing deal.

“Most crowd-funding platforms will tell you that the initial impetus must come from the developer’s own network,” Choudary said. “What they don’t tell you is to get to the point where they push the game to their own private lists of backers you need a lot of backing activity. This might still be the best route to go for traditional game developers and lifestyle businesses not wanting to lose control but the skills that often allow some developers to succeed at this kind of marketing are different than the type of skills needed to make game businesses” worthy of an exit.

On the other hand, famous game developers with older properties that can be remade into new games might prove very popular.

“Crowd-funding might give a second life to a whole class of companies,” Fargo said. “You can get a lot more creativity and innovation and you don’t have to kowtow to a major publisher.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More