To predict the future, look at what really smart people are doing for fun.

That’s the advice from Tim O’Reilly, founder of O’Reilly Media and a proven futurist and coolhunter. O’Reilly started making manuals for Unix long before Unix was cool, got into the PC revolution early on, launched one of the first commercial websites, and launched Make magazine long before the “do-it-yourself” movement had taken off.

“You look at so many industries, and it begins with people having fun,” O’Reilly said.

For example, the PC revolution began with a bunch of smart nerds (and a few college dropouts) hanging out at the Homebrew Computer Club, showing off things they’d hacked together in their spare time.

Now the really smart people are probably building 3D printers from Makerbot kits, or else creating their own high-powered lasers or animatronic, flame-breathing dragons. Sure, these devices aren’t practical mass-market devices. But then, the Apple I computer that Steve Wozniak put together with a wooden case he built by hand in his shop wasn’t a mass-market device either, and look how far that idea got.

O’Reilly spoke at a panel this week, cosponsored by General Electric and Monocle magazine, about the convergence of craftsmanship and technology. About a hundred people gathered to hear a handful of experts talk about craftsmanship, apprenticeships, mass customization, and the art of making delightful products that “romance” the customer. The audience was heavily weighted towards designers, to judge from their eyewear alone (lots of glasses with chunky plastic or wood frames — but, alas, no actual monocles).

Another of the day’s speakers was Carl Bass, president and chief executive of Autodesk. Bass said he is himself a maker, having dropped out of college 35 years ago to work on boatbuilding, among other things. (He eventually completed a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Cornell, so he’s no slouch academically.)

“In some ways we’re rewriting the fundamental economic equation of the industrial revolution,” Bass said. In other words, the premise of the industrial revolution was that you could radically cut the prices of consumer goods, while maintaining their quality, through high volume production. Now, thanks to 3D printing and other “mass customization” technologies, you can have high quality products in small volumes — even one-offs — without exorbitant prices.

“There’s no difference when I make one and when I make 1,000,” said Bass. “That was never true in craft.”

Mark Hatch, the chief executive of TechShop, concurred. TechShop offers a giant workshop full of tools that you can use for a single monthly membership fee, sort of like belonging to a gym. The company has five locations around the U.S. and is opening five more this year, Hatch said. The company also offers classes to train people in how to use equipment in its shops, such as precision lathes and CNC machines. Essentially, it makes very high-end industrial tools accessible to a wide variety of people — and that’s only possible because these machines are controlled by increasingly sophisticated software.

“The combination of software tools with cheap, powerful, easy-to-use capital tools is completely remaking industry,” Hatch said.

Hatch told me after the event that the interest in hardware goes deep. Last year, he said, U.S. universities awarded more degrees in mechanical engineering than they did in software engineering, in contrast to the usual ratio.

Hatch and Bass are not the only ones excited about the resurgence of hardware hacking and the prospects for tech craftsmanship. Charles Chi, the executive chairman of digital imaging startup Lytro, said the combination of sophisticated overseas manufacturing and the accessibility of social media branding tools makes it unusually easy to start an electronics company today. In the past, you might have had to spend millions building a factory and millions more buying Super Bowl commercials. Now you can outsource production (and even much of your product’s engineering) to Chinese “original design manufacturers” (known as ODMs) and do aggressive branding on Twitter and Facebook for a fraction of the price.

“It’s almost the golden age for consumer electronics,” Chi said.

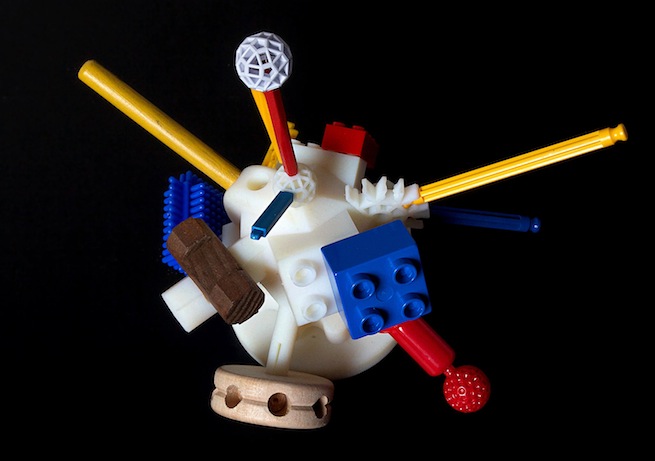

But back to the 3D printers. You may wonder what anyone does with a 3D printer, and it’s a thought I’ve had myself many times. Well, here’s one answer: The Free Universal Construction Kit is a set of 80 different widgets that kids can use to connect different kinds of toys together: Lincoln Logs to Lego, K’nex to Duplo blocks, Zoobs to Bristle Blocks. There’s even a universal adapter brick, a fist-sized monstrosity that lets you plug in one of every supported toy. (Even more awesomely, it appears to be based on the shape of an isocahedron — also known as a d20.) Needless to say, I would have loved having this kit when I was 8 years old.

The people behind this kit are giving it away for free. (And they’ve made an excellent 30-second commercial for it, which wouldn’t be out of place on Nickelodeon.) But here’s the catch: They’re not selling physical objects at all. Instead, they’re making .STL files available that anyone can download and use with their 3D printers to create these doodads. If your kids want this kit, you need a 3D printer.

If you don’t have one of your own, may I suggest TechShop?

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/37778172 w=500&h=281]