Every developer should wish it were Valve. The creator of the Half-Life series has a certain quality that makes its products nearly universally praised by critics and fans. Up until now, many onlookers have credited Gabe Newell, Valve’s founder and managing director, with guiding the developer (and digital retailer) to its unprecedented success, but the recently released Handbook for New Employees suggests that a strong personality at the top is only half the story.

GamesBeat contacted Valve’s vice president of marketing, Doug Lombardi (although after reading the handbook we have to wonder if that is a title he concocted for himself), and he confirmed the book’s authenticity. Now that we know it’s real, what lessons can other developers and publishers learn from the way Valve works? We’ve pinpointed four key aspects from the handbook’s text that others can emulate.

Have a sense of humor

Like the award-winning puzzle-based-shooter Portal, Valve’s Handbook for New Employees is filled with delightfully witty writing. For example, in a section of the guide that describes some of the office’s amenities (a gym, a massage parlor, a full-service cleaner), the book tells the new hire to relax and enjoy these things. “It’s not a sign that this place is going to come crumbling down like some 1999-era dot-com startup,” reads the handbook. “If we ever institute caviar-catered lunches, though, then maybe something’s wrong. Definitely panic if there’s caviar.”

Funny pictures and humorous writing can do a lot to humanize what would otherwise be a soulless entry from the human-resources department. Making people smile while giving them instructions makes it clear that real people put in an effort. That’s something others will respond to, and it could create a caring atmosphere that ends up positively affecting the final consumer products.

Care for your employee’s families

Care for your employee’s families

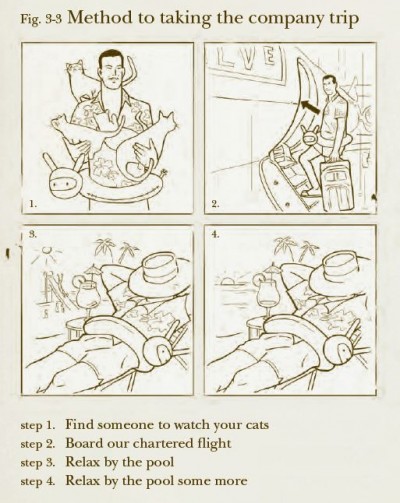

Valve makes a lot of money. According to the handbook, its profitability per employee is higher than Google, Amazon, or Microsoft. That makes it pretty easy to take everyone, along with their families, on a company vacation, which is something that the Washington-based corporation does once a year. That’s not realistic for every studio, but that doesn’t mean others should forget about their employee’s home life.

The Valve handbook opens up with a dedication that reads: “To the families of all Valve employees. Thank you for helping us make such an incredible place.”

A “thank you” goes a very long way. It acknowledges that the employees bring their work home with them, and their families struggle with it as well. The difference between having the support of loved ones and not having that support is the difference between a satisfying job and a miserable one.

The guide also features a timeline of significant events in Valve’s history. It marks the first company vacation in 1998 to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico and notes that 30 employees attended with zero children. At the end of the timeline, it notes the latest vacation to the Big Island of Hawaii in 2012. This time, 293 employees brought along 183 children (although I suppose the guide didn’t specify that these were the employees’ children). Have you ever worked for anyone who knew the total number of children that its employees have? Again, knowing something tiny like that shows a tremendous amount of humanity, and it’s something that any company can do regardless of its budget.

Treat your employees like adults

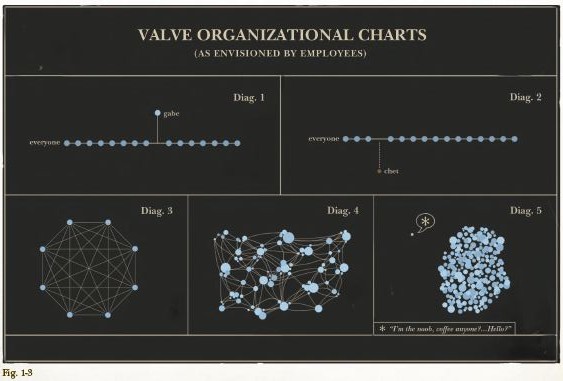

After reading the entire manual, the obvious standout revelation is Valve’s “flat” organizational structure — that is to say that it doesn’t have one. Everyone decides which project that they should be working on.”This company is yours to steer,” reads the guidebook. “Toward opportunities and away from risks. You have the power to green-light projects. You have the power to ship products.”

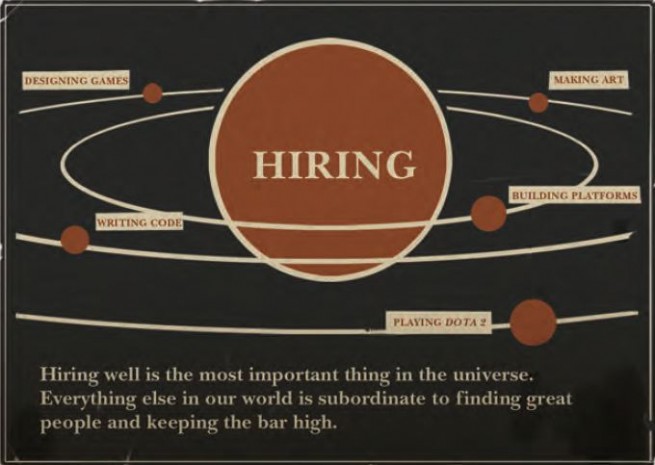

Sounds crazy, right? Not so much. The Handbook for New Employees puts a huge emphasis on hiring great people. “When you’re an entertainment company that’s spent the last decade going out of its way to recruit the most intelligent, innovative, talented people on Earth, telling them to sit at a desk and do what they’re told obliterates 99 percent of their value,” Valve writes.

Maybe it’s too much to ask the rigid hierarchies at other development houses to drastically shift to this free-loving hippie way of conducting business, but it shouldn’t be too much for those companies to treat their employees like adults. After all, hiring someone is a sign of trust. Extend that trust to every aspect of the position.

When you give freedom to creative people, it puts the onus on them to make something on their own instead of waiting around to be instructed. It also makes the employee/employer relationship feel more like a partnership. It says “we’re both adults who can benefit from one another” rather than “sit down and get your work done like a good boy.” It builds respect which in turn will build pride in the work and the company.

Mitigate the fear of failure

Fear of failure is a key player in the struggle for perfection. No one notices when the work stops at good enough, but a failure to reach greatness will draw a lot of negative attention. When a job is on the line, a lot of people will quietly settle for average. Valve takes a different tactic:

Fear of failure is a key player in the struggle for perfection. No one notices when the work stops at good enough, but a failure to reach greatness will draw a lot of negative attention. When a job is on the line, a lot of people will quietly settle for average. Valve takes a different tactic:

“Providing the freedom to fail is an important trait of [Valve] — we couldn’t expect so much of individuals if we also penalized people for errors,” the handbook reads. “Even expensive mistakes, or ones which result in a very public failure, are genuinely looked at as opportunities to learn.”

Again, this puts the responsibility on the creative person. They can no longer point to negative repercussions as an excuse for not trying something new and amazing.

The human corporation

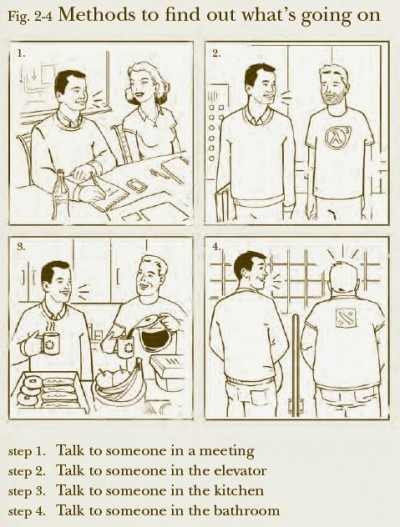

That’s not to say Valve is perfect. The handbook even has a section titled “What is Valve not good at?” It lists things like “disseminating information internally” and “making predictions longer than a few months out.” Most interestingly this page of the book points out that the developer misses out on some potential employees who prefer to work in a more traditional environment, which acknowledges that these methods aren’t for everybody. Still, the motivation behind these actions is something that every employer can learn from.

Humanity is the unifying theme that separates Valve from other game companies. Whether it’s respecting someone enough to trust them to do what’s best or sprucing up typical human-resources copy with pleasant humor, it’s all a sign that the people who comprise the staff care about one another and the work they produce.

Now, if only we could figure out a way to make them love releasing Half-Life 3 just as much.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More