At a time when the largest industry in entertainment is focused on the next big thing, it’s easy to forget the past of video games. Who is helping ensure that our gaming heritage is preserved for future generations to enjoy, study, and learn from? The answer is Jon-Paul Dyson, director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) at the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY.

At a time when the largest industry in entertainment is focused on the next big thing, it’s easy to forget the past of video games. Who is helping ensure that our gaming heritage is preserved for future generations to enjoy, study, and learn from? The answer is Jon-Paul Dyson, director of the International Center for the History of Electronic Games (ICHEG) at the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY.

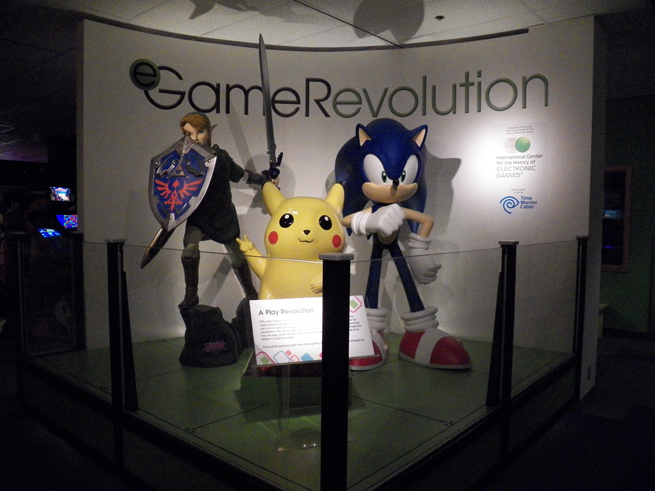

Dyson is leading the charge to protect our past by curating a unique museum that includes an extensive library and archives, over 140 arcade cabinets, 12,000 console video games, every major home console produced since 1972, dozens of personal computers, and more than 200 different handheld electronic game systems. For his efforts, he was recently named in Game Developer Magazine’s prestigious “The Game Developer 50” listing. Jeffrey DiOrio recently interviewed Dyson about the museum and its role. Here’s an edited transcript.

GamesBeat: What is (your) mission?

GamesBeat: What is (your) mission?

J.P.Dyson: ICHEG’s mission is to explore and preserve the history of video games and their impact in the world, and the way people play but also the way they live, the way they learn, and the way they relate to one another.

GamesBeat: How did ICHEG get its start?

J.P. Dyson: ICHEG itself is a natural outgrowth of the collections of The Strong. The Strong has the most comprehensive collection of toys, dolls and games (in the world), and as we were looking at how play was changing, we realized that video games were having a bigger impact on play than anything else. And not just at play, but so many aspects of human life. So we began collecting video games in 2009, and we launched ICHEG. And since then the collection has grown from a very small collection of about 10,000 games and related artifacts to more than 36,000 games and related artifacts today.

GamesBeat: Did the idea to create a museum dedicated to video and electronic games experience any resistance?

J.P. Dyson: First of all, there’s a natural correlation or connection between older forms of play and newer forms of play, such as between a doll house and The Sims, Dungeons and Dragons and World of Warcraft. And any time you get a new form of media or new form of play, there are controversies. For instance in our exhibit ‘American Comic Book Heroes’ we explore some of the controversies over comic books. And the ways that people thought comic books were threatening and caused problems.

You see the same issues with the rise of Film and the rise of Television. So with video games you have some of those same issues. Worries of ‘What are the contents of the material?’, ‘Are people wasting their time playing it?’. So we’re interested in exploring those issues, not just dismissing them. Issues like violence. Issues like the educational benefits, or not, of video games. And so within the broader community of people concerned about play and children there have been sometimes when people have said ‘Well, I’m not sure if people should be spending as much time as they do playing video games’. So I think it’s more from that stand point that we’ve gotten, at times, questions.

But I think, when articulated, even people suspicious of video games still understand the impact they are having. So once you understand the impact they are having I think that people get the importance of why we need to do this. That if we don’t act to preserve a record of video games, there’s a chance much of this will be lost.

GamesBeat: So really it’s never been a question of the breadth of impact of the video gaming industry and whether that warrants its own center, but really maybe some of the more philosophical questions on whether this (gaming) is a good thing, or not.

GamesBeat: So really it’s never been a question of the breadth of impact of the video gaming industry and whether that warrants its own center, but really maybe some of the more philosophical questions on whether this (gaming) is a good thing, or not.

J.P. Dyson: Yea, I think so. I mean, I imagine there are probably some people who resist the idea of preserving video games in a museum. It seems like ‘Well, is that what museums are for?’. But I think that we’ve been able to make a really compelling case that this is what museums need to be preserving.

GamesBeat: How is ICHEG preparing to conserve gaming history at a time when games and gaming content are increasingly distributed digitally?

J.P. Dyson: If I look at the bigger picture of ‘how do you preserve a video game’, it’s a hard problem as you raise some of these issues. So let me take a step back and talk about our approach. At the moment we are pursuing a 5-fold strategy for preserving video games. The central thing that we’ve been concentrating on, initially, is collecting the physical copies of games and hardware.

But we recognize that alone is not (enough). The second thing we’re collecting are printed materials, or mass manufactured materials without the games. So this would be things like game guides, gaming magazines, ephemera that’s produced related to the games, that sort of thing. They give you insights into the games, how the games were played, how they were created, interviews with authors. Preserving those are really key, that’s why we’ve built this collection of over 10,000 video game and computer magazines.

Going further into this, you go from these mass-produced printed materials to the 3rd thing, archival materials. This would include game designer notes, business records, marketing materials, oral histories. These are all important things, such as Will Wright’s notebooks or Ralph Baer’s notes, those unique archival materials. The 4th thing is doing video capture. So capture a record of the game at play. Now this is not the same as being able to load the game up and play it. But at least it gives you some sense of what the game was like, what was the feel of the game. So historians who wanted to know a game from 20 years ago, they could look at a video record of that. So that’s where we have this grant funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to capture video from about 7,000 games in our collection.