Search engine marketing guru Danny Sullivan has asked the FTC to review Google’s treatment of paid results within, next to, or near organic search results.

Search engine marketing guru Danny Sullivan has asked the FTC to review Google’s treatment of paid results within, next to, or near organic search results.

Remember this? It’s from Google’s 2004 founders’ IPO letter:

Our search results are the best we know how to produce. They are unbiased and objective, and we do not accept payment for them or for inclusion or more frequent updating.

Google very clearly stated that its search results are not for sale. This was a significant statement to make, because in the early 2000’s the integrity of search results as an honest and accurate reflection of what the web actually contained was very much at issue.

Google’s IPO letter also contained this sentence (emphasis added):

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

We also display advertising, which we work hard to make relevant, and we label it clearly.

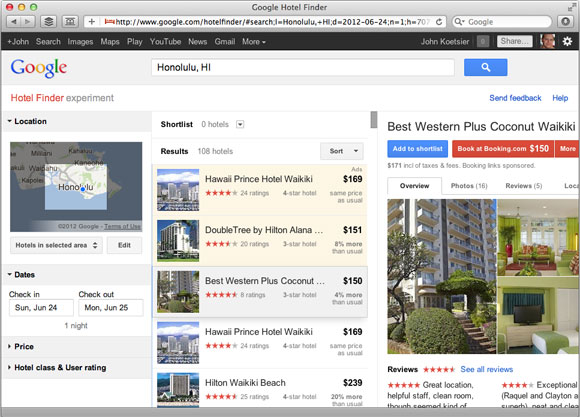

“Clear labelling” is what is most at issue right now. Sullivan has been writing about Google’s changing ad inclusion policies for weeks, focusing on Google’s vertical search engines for hotels and flights.

Google’s challenge is that the role of a search engine is changing from just finding information to enabling actions. This is largely a user experience-driven shift: as a user, your goal is to book a flight. A service that allows you to both find the best flight with the best price and book it immediately is often preferable to one that teasingly reveals the best flight but won’t let you book it. For hotels and flights, Google’s services have evolved to enable just that.

But it’s also a revenue opportunity. Not only is there more money to be made when companies pay to be included in search engine results, there’s transactional revenue when search becomes commerce — a referral fee when the user purchases the flight or books the hotel.

But there are three problems.

The first problem comes when users don’t know which companies have paid for inclusion. The second is when it’s not clear how much Google stands to gain from referring a paying customer to a service. (If Google makes $10 for a client who books with American Airlines versus $5 for a client who books with Air Canada, what controls are in place to ensure that American is not getting preferential treatment?) And the third problem is simply visually distinguishing ads from results.

For example, can you find the “Ads” designation in this image?

The ads are the two results at the top of the list in color, but to the average user, it could simply appear that they are search results that are highlighted — perhaps because they are most relevant. The format is identical, the look is the same: just the background color and a tiny “Ads” differentiate it from other results.

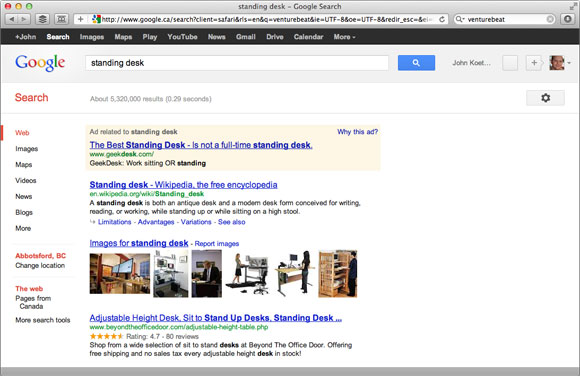

Contrast this with standard web results on google.com. The ad unit is much more clearly displayed — it is much more obvious what is an ad on this page and what is not. Not only is the display clearer, the language is much more obvious. Both “Ad related to standing desk” and “Why this ad?” indicate to the user that this is indeed, a paid placement.

Sullivan has been reporting on search engines since 1996 and runs the popular Search Engine Land website. He has asked the FTC not only to review how search engines are treating their 2002 guidelines but also to consider updating the guidelines for 2012 and following.

Image credit: AHMAD FAIZAL YAHYA / Shutterstock.com

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More