After cloud gaming leader OnLive ran out of money in August, the future of cloud gaming became, er, cloudy. Rival cloud gaming service Gaikai had sold itself to Sony for $380 million, but OnLive’s failure to gain enough consumers to offset the costs of its cloud infrastructure raised questions about whether cloud technology was economical for games. Cloud gaming let a user play a high-end game on a low-end PC simply by logging into OnLive, which executed games in web-connected data centers that computed the game and sent images to the user’s machine in real time. OnLive launched in 2010, but too few subscribers materialized. Surrounded by free-to-play games, OnLive tried to sell consumers on instant access to the cloud and the capability to log in from any machine.

But Phil Eisler, the general manager of GeForce Grid Cloud Gaming at Nvidia, told us in an interview that he believes the technology is “hugely disruptive.” And he thinks it’s ready and numerous cloud gaming projects will appear in 2013. Nvidia is adding cloud graphics technology to its graphics chips and making graphics cards available for cloud gaming data center servers. In doing so, Nvidia enables service providers to accommodate multiple gamers per server and thereby make more economical use of their server infrastructure. Here’s an edited transcipt of our interview with Eisler.

GamesBeat: Where did the interest in cloud gaming begin for Nvidia?

Phil Eisler: Cloud began with some software architects about four or five years ago. They were looking at encoding the output of the GPU and sending it over the internet, and experimenting with that. They build that into a series of capture routines and applications programming interfaces (APIs) that could capture the full frame buffer or part of the frame buffer.

Phil Eisler: Cloud began with some software architects about four or five years ago. They were looking at encoding the output of the GPU and sending it over the internet, and experimenting with that. They build that into a series of capture routines and applications programming interfaces (APIs) that could capture the full frame buffer or part of the frame buffer.

GamesBeat: Why were they thinking about that? They had just watched things in the market, where the cloud was already starting to … ?

Eisler: I think it’s just a precursor to a remote desktop. People have always thought that they want to get rid of all the wires around a computer — the capability to remote in and use the IP protocol to send displays anywhere. The concept, I guess, has been around in different forms going back to X terminals and things like that, using different methods. It’s always been a useful feature when you encounter it, but it’s never gained great traction in the marketplace. X terminals kind of went away, their original incarnation. But I think now, with all the multiscreen proliferation, it’s generated a lot of incompatibility between applications. There’s even more call for it now. And then it kind of evolved into the hardware team actually adding hardware encoders to graphics chips to make it more functional, make it scale better, than passing all that data back to the CPU. It’s a lot more efficient in the computer system to do the encoding on the GPU.

GamesBeat: It seems like it would be a little less interesting to you guys if it was purely enterprise. But when gaming came into the picture, it maybe has spurred more interest at Nvidia.

GamesBeat: It seems like it would be a little less interesting to you guys if it was purely enterprise. But when gaming came into the picture, it maybe has spurred more interest at Nvidia.

Eisler (pictured right): Yeah. I think it also enables Nvidia to expand beyond PC gaming. Now we can reach the television. We’ve always participated in television gaming through Xbox and PlayStation, but we see the opportunity to support TV gaming directly. And so that big-screen gaming experience being delivered from the cloud is appealing to us. We think that’s a direction for the future.

GamesBeat: That’s when you have Nvidia hardware in data centers that are streaming things into TVs, right?

Eisler: We look at it both ways. A lot of our focus is on that, putting in the data centers and streaming to TVs or tablets or phones. Or PCs or Mac products. But also, the idea that if you have a high-end gaming PC in your home, you could actually stream it to screens around the home yourself. So it’s both data-center-based and local home-server-based.

GamesBeat: OnLive came out in 2009. Were people already thinking about cloud gaming and talking about things like this?

Eisler: Sure. One of the great things about a company like Nvidia is it does invest a lot in long-range research. We have research teams internally that work on a lot of long-range things. We had started doing early work on remote desktops prior to OnLive’s existence. Actually, we filed quite a few patents early on in that area. But then we worked and supported most of the early cloud gaming startups: OnLive, Gaikai, and such. We still work with the remaining ones, as the market evolves and grows.

GamesBeat: The idea that, say, your graphics chip hardware might change because of the cloud, was that also pretty early?

GamesBeat: The idea that, say, your graphics chip hardware might change because of the cloud, was that also pretty early?

Eisler: The planning cycle for a new GPU is at least two years, so … Kepler came out last year. It would have had to begin in 2009 — and probably earlier than that. We decided to enable the remote desktop through GPU hardware, which definitely makes it more scalable and more hardware-friendly. And now that we have our first generation built, we also look forward to the ability to improve remote desktop or cloud gaming hardware with each generation. Next-generation chips are learning a lot, and will be much better at delivering more concurrent streams of better experiences to more people.

GamesBeat: I think the way your chief executive, Jen-Hsun Huang, described it was that the hardware now, rather than expecting every task coming into it from just one PC, can receive a task from any Internet protocol address.

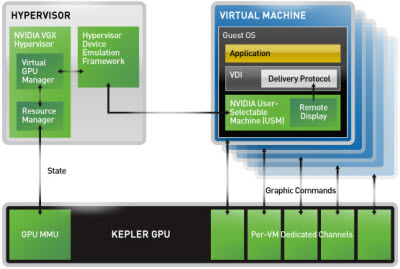

Eisler: Yeah. The concept of a CPU being shared as a virtual machine has been around since the ’60s. With hypervisors that then enable that…. Part of our VGX effort is to develop the hardware and software for a GPU hypervisor to enable the virtual GPU. So we are going to apply that to gaming, which provides us even more scalability of sharing a GPU as well as the CPU in the system so that both are virtualized. Virtualizing a GPU is a little bit different and more challenging than virtualizing a CPU, just because of the nature of the tasks and the data sets that are associated with it. But we’re solving those problems. The early results are promising, and I think we’ll get better with each generation of hardware and software. That’s a major effort for us right now.

GamesBeat: So with Kepler, you could do something like four users on a single GPU?

Eisler: It has the ability to encode four simultaneous streams. The actual virtualization of the GPU can be more than that. We have some game partners that do more than for. The encoding, currently, depends on the resolution and framerate. But practically, it’s about four.

GamesBeat: I think Jen-Hsun mentioned that you could go to 16 users over time. What makes that happen?

GamesBeat: I think Jen-Hsun mentioned that you could go to 16 users over time. What makes that happen?

Eisler: I think it will get on a Moore’s Law type of trajectory, where the number of streams per server will double every year. I think the original Gaikai and OnLive implementations, which are a couple of years old now, are one stream per server. We announced now that K520, which does two per board… Most of the systems have two in them, so that makes four. That’ll be this year. Next year we’ll see eight, and then 16 and 32. I think it’ll go up for a while.

GamesBeat: One thing surprised me about the early architecture of the cloud gaming infrastructure. It didn’t seem very efficient. They studied the issue for so long, for a decade or so. I would have thought they might have come up with something more economical. But in the end result, with OnLive, it looks like the infrastructure was pretty costly. Is there a conclusion you can draw from that? Have the infrastructure requirements evolved over time?

Eisler: Yeah, I think that was part of the OnLive story. I don’t think it was all of it. Maybe not even the most important part. They built something like an 8,000 concurrent stream capacity, which in a world of a billion gamers is not a lot. I think Gaikai built something like half that.

GamesBeat: And both of them were mostly able to lease this server capacity, right?

Eisler: Yeah. I think Gaikai used a company called TriplePoint Capital. So they were both able to lease it. It was a heavy burden on them as startups, from that standpoint. But you’re right. They only supported one game per machine. They were early pioneers and they were focused mostly on getting it working. When they started, nobody was doing it, so they had to invent the encoding technology, the virtual machine technology, the distributed game technology. Being small startups, they were mostly focused on the quickest path to make it work, which is what they did. They didn’t really get to the second phase, which was cost-reducing it and adding more concurrency. And they did it largely without a lot of support from even us. In the early days we gave them little bits of help, but not a lot. We didn’t design products for them. Grid was the first time we designed products for the market that were made for that purpose, so it makes it easier for them to scale it out.

GamesBeat: So custom servers are not as efficient as in the day and age when these capabilities are built into general-purpose servers.

GamesBeat: So custom servers are not as efficient as in the day and age when these capabilities are built into general-purpose servers.

Eisler: One thing is, we’re offloading their encoding parameters. They were either doing it through external hardware or through software on the CPU, both of which involve a lot of data transfer and power consumption. Because we’re doing it on the GPU, that offloads the CPU for more games running and reduces the power and enables more concurrency, so you can get more simultaneous streams per server and reduce the cost per stream.

GamesBeat: And then there’s more data centers with servers with GPUs in them these days.

Eisler: They’re coming, yeah. We had to work with the people who build servers, whether it’s Quanta or Dell or Super Micro, to build space for GPUs into their architecture. We’ve done that now, and we actually pioneered that, primarily through our Tesla group. We’re leveraging a lot of the infrastructure that was built for that to plug our GPUs in. That’s working out well and making it easy to assemble and put GPU servers into the data center.

GamesBeat: What’s the part you call the GeForce Grid again?

Eisler: It’s a server board product, so it’s passively cooled. It doesn’t have its own fans. It’s designed to use the fans from a server chassis. It has multiple GPUs on it. The one we have announced has two GPUs on it. And then there’s a software package that comes with it that enables the control of the capture and encoding routines to enable streaming of the output.

GamesBeat: So the more that the cloud infrastructure people deploy these, then the better able they could be to support the whole cloud gaming industry.

Eisler: Yeah. It’s possible that the industry could shake out into different levels. There are infrastructure-as-a-service providers that operate data centers and we’re talking to those folks. They’re looking at just putting capacity in place, and then anyone who’s in the game distribution business could layer their service on top of that. That would be one way of financing the build-out of it. And then there’s other people who want more of a wholly integrated solution, where they want to purchase their own servers and rent the games, or for that matter any application, directly themselves to consumers or business users.

GamesBeat: What sort of expectation should consumers have about how much progress they’re going to see? You guys have the figures, like the minimum requirements of bandwidth that you need for a good cloud gaming experience. 30 megabits a second on a desktop line and 10 megabits on a mobile device. …

GamesBeat: What sort of expectation should consumers have about how much progress they’re going to see? You guys have the figures, like the minimum requirements of bandwidth that you need for a good cloud gaming experience. 30 megabits a second on a desktop line and 10 megabits on a mobile device. …

Eisler: It’s variable bit rate, but a lot of it… A good tradeoff of experience versus bandwidth is 720p, 30 frames per second and about five megabits per second. That’s where we think it’s pretty good. We have the ability to go higher. We could 1080p, we could do 60 frames per second if you’ve got 15 or 20 megabits per second, but not many people do, at least today. And then we can also go lower, down to 480 and two megabits per second, but there’s kind of a range. The sweet spot, we think, is 720p, 30 frames per second, five megabits per second.

GamesBeat: I think that’s exactly what OnLive targeted.

Eisler: Yes. OnLive and Gaikai both were in that range, which has a lot to do with the current broadband infrastructure.

GamesBeat: I don’t know whether consumers found it to be good enough. They tried that for a while and then they didn’t wind up with too many subscribers, so… I don’t know if the consumers just weren’t aware of it, or if they didn’t actually like the experience.

Eisler: Bandwidth is one thing. The other thing is also latency. They had a lot of latency in their system associated with the encoding and the network infrastructure. One of the things we’ve done with Grid is do a much faster capture and encode. We’re able to save about 30 milliseconds of latency, which helps a lot. We’re also working on client optimizations, which can save maybe another 20 milliseconds of latency. The latency feel was certainly a big part of it. Also, with Moore’s Law, we will improve the bandwidth and resolution. Even in countries like Korea… I was at a product launch there about a month ago with the LG U+. They were announcing two choices for their TV service. One was 50 megabits per second and the other choice was 100 megabits per second. There, we can go 1080p, 60Hz, and it’ll be a beautiful picture. I think that is the future for this country as well. I think there was an experience problem. That might have been the larger problem, even over the density and cost side. We are working on that one hard too, in terms of improving the quality of the experience, reducing latency, and improving the visual quality of it. And then lastly, it’s access to first-run content. The content that OnLive had was a little bit older, and so we’re trying to work with developers to have fresher content available.