Video game developers don’t seem to design their creations to last for decades. Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda might hold up over the years, but others, like Duck Hunt, become trapped in limbo as technology moves beyond them. When Activision releases a new entry in the Call of Duty series, the true intention isn’t for it to build an audience over several years but to hit all at once and stay successful until the next big installment in the series launches (usually the next year). This same mentality appears in some tech companies, no matter if the end products are computer components or software: If you want to maintain profits, you have to get things done quickly.

So it is a large leap to go from fast-paced technology development and headfirst into designing board games, but that’s exactly what Days of Wonder cofounders Eric Hautemont and Mark Kaufman did. Days of Wonder is the company behind German-style games like Ticket to Ride and Small World. German or European-style board games emphasize strategy over competition and often have economic themes and promote fairness and inclusion that keeps players at the table until the very last turn.

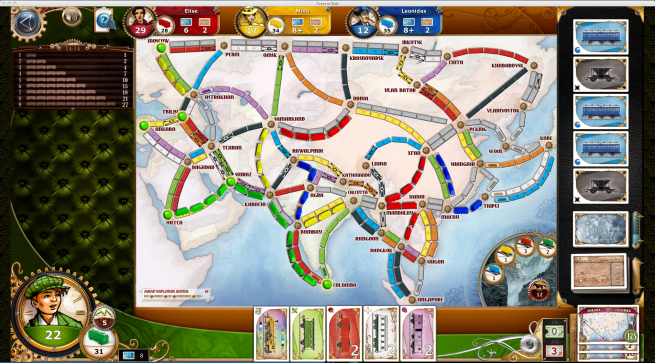

Days of Wonder’s first game, Ticket to Ride, actually won the German Spiel des Jahres (game of the year) award in 2004, making it the youngest company to ever win that title.

“Our exit strategy is death,” said Hautemont in an interview with GamesBeat. “People always ask me what our exit strategy is if the whole board game idea doesn’t work out, and I like to say it’s death. When you develop board games you are designing a product that will last, hopefully for decades, hopefully longer than you.”

Hautemont and Kaufman started Days of Wonder in 2002 with $600,000 and in a year it was already profitable. The Los Altos, Calif.-based company has 16 employees and has managed to increase both revenue and profitability every year. This stems from the company’s development philosophy that dictates that making quality games requires spending a great deal of time refining them.

“For video game and tech companies it’s always go, go, go,” said Hautemont. “Board games can’t follow that schedule and remain profitable. The idea is that a board game, say, like Monopoly, is initially successful, but the real profit comes from decades of growth.”

“We do have a calendar we work by,” said Kaufman. “But how do we take the time to make the product we want and that the end-user will be happy with? If we can’t get it done, we have to consider if a game is really as good as we want it.”

Monopoly gained popularity 77 years ago but is still a household name. Hasbro puts new touches on the game occasionally, but one fact remains constant: People like playing Monopoly and pass that tradition on. Families years from now will still play it and keep the interest alive for generations.

Days of Wonder is rare in that it expends a great deal of effort when designing or publishing board games, but it also creates all the digital versions in-house. So Ticket to Ride on iOS and Steam came from the same 16-man team that helped make the tabletop game.

When Apple unveiled the original iPad, Ticket to Ride was one of the very first games available for it in the app store. Since then, it has sold over a million copies and ranks 56 on the list of top grossing apps and first among other iOS board games.

But digital platforms are not as sustainable as physical games. The original iPad isn’t nearly as powerful as its shiny retina-displayed sister, and some games no longer work for it now that developers are embracing the new iPad’s faster processor.

“You don’t have to worry about tables changing,” said Kaufman. “I mean, you can count on there always being a surface to play a board game on. With technology, things are always advancing and that can present a problem. Right now, all Days of Wonder products in the app store are compatible with all models of iPads, though the iPad 1 versions don’t utilize features that the newer tablets allow. We will support a platform as long as there are customers using it who want our product.”

It’s inevitable that games just won’t run on the original iPad anymore, but Days of Wonder takes the sensible approach of slowly evolving its products and not completely dropping older platforms, like other iOS developers have.

“I think many companies can benefit from slowing down production,” said Hautemont. “THQ, Zynga — quality comes from taking time with development and production and not forcing things out into a market quickly.”

This strategy might have come in handy when THQ poured millions into the uDraw tablet that saw success on the Wii but fell flat on the 360 and PlayStation 3. The result was a very shaky fourth quarter for THQ and an unprecedented stock plunge. But Days of Wonder also doesn’t have to worry about keeping shareholders happy with constant new intellectual properties and blockbuster games and can take a slow and steady approach where developers have to keep pushing forward.

“Every company is different,” said Kaufman. “If you are a public company, you have a need to constantly be moving, or else you’ll get in trouble with your shareholders. We have no intention of ever taking Days of Wonder public.”

Hautemont and Kaufman found a niche that works for them. They left the fast-paced world of publicly traded companies and to forge ahead on their own, doing something they enjoy on their own time. Their business model works well for board games that are only truly successful when they can stand the test of time. But perhaps video game companies should take a step back and see that a quality-driven revenue might ultimately be more sustainable than perpetually taking a risk on potential triple-A titles.

For now, averaging one new game a year and maintaining a high level of polish across all its products is what Days of Wonder wants to do and probably will still do 50 years from now.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More