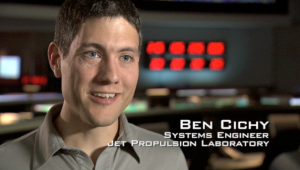

Mars may once have looked like Earth. It has seasons, polar ice-caps and once supported shallow seas and flowing streams. So did it also once support life? The Mars Curiosity Rover’s chief software engineer Benjamin Cichy just gave a rollercoaster of a talk at LeWeb in Paris on the huge software effort and nail-biting suspense involved in getting the rover to Mars.

NASA has been sending spacecraft to Mars since the 1960s. The first 12 missions failed disastrously. Overall, one-third of all missions to Mars have failed. The Curiosity Rover is the biggest and most complex that NASA has even built, the size of a small car, and it was landed using a completely novel set of technologies.

It took five million lines of code to teach the Rover how to land. A heatshield made from an entirely new material protected the spacecraft during entry. The biggest parachute ever built was used to slow its descent towards the surface down to a mere 300 km per hour. At this breakneck speed the cord was cut and a jetpack attached to the top of the Rover fired up to slow it down to 2.5 km per hour and lower it down towards the surface. Finally the attachment to the jet pack had to be cut before it ran out of fuel and crashed down on top of the rover.

It took five million lines of code to teach the Rover how to land. A heatshield made from an entirely new material protected the spacecraft during entry. The biggest parachute ever built was used to slow its descent towards the surface down to a mere 300 km per hour. At this breakneck speed the cord was cut and a jetpack attached to the top of the Rover fired up to slow it down to 2.5 km per hour and lower it down towards the surface. Finally the attachment to the jet pack had to be cut before it ran out of fuel and crashed down on top of the rover.

Even worse, there was no way to test if all of this would work together until the landing itself. NASA called it “The 7 minutes of terror.”

The Curiosity Rover’s two-year prime mission is to investigate whether conditions in Mars may have been favorable for microbial life. It is equipped with a 2 meter robot arm, cameras, spectrometer, telescope, chemistry and minerology equipment. It even has a laser which can be pointed as a rock to determine its composition.

When the Rover has nothing new to report it sends back a packet to Earth. As software engineers do, Cichy inserted his own name and those of the other NASA developers into the 1000 characters available. He also added a quote from Carl Sagan: “We began as wanderers and we are wanderers still.”

We met with Benjamin Cichy for a chat after his presentation for some forward thinking perspective.

VentureBeat: What’s the next step, the closest in time, and the big picture?

Benjamin Cichy: We’re just getting the Rover to be able to explore Mars. It’s been on the surface of mars for four months now. We have a two-year mission, we’re just getting started. What we’re trying to do is to drive across the surface of this crater and get to the base of this mountain that we landed on. We’re going to go read the history book of that mountain — each layer on that mountain is a chapter in the book of Mars. We’re going to learn about Mars by reading it from the oldest layer at the bottom, to the most recent layers at the top. That’s what’s next for this mission.

VB: What do you hope to find out?

BC: Whether or not Mars ever could have been a place to have life. Was there a life once on Mars before? Everywhere that we look for life, we know we need to look for three things. An energy source, water an the organic molecules that can bring life — are there building blocks of life on Mars?

VB: Which would be the next planet that you would want to explore, that to you as a scientist think could hold the key to other potential forms of life?

BC: There’s a lot of other exciting bodies in the solar system and they’re not all planets, they’re moons. Moons of Saturn and moons of Jupiter. One in particular, Europa, is very interesting — in terms of maybe it’s an environment that could harbor life now; maybe there is a liquid ocean there on Europa. Maybe there’s something interesting to find out on these moons of other planets. What I’d really like to see is some missions to go off explore those other bodies in the solar system and really just look for how pervasive these environments are that could have once supported life.

VB: This is LeWeb and the theme is the “Internet of Things”. How does Mars Curiosity Rover relate to that?

BC: This really is the first mission that we’ve had since the internet has literally exploded into a hyper connected web: social media, connected devices…. the Curiosity Rover in a way now is the further outpost of a connected device, and on the surface of another planet. What it does is that as Curiosity sends out these images, they are sent all over the world, broadcasted through social media and they get traction elsewhere in the world in a way that they never did before. Images are retweeted thousands of times and often times even before the scientists are able to take a look at them, the general public sees the images. That’s immediate access to the exploration process, participation in the exploration. This is really the first time.

VB: When do you think we’ll be able to have shuttle trips going back and forth between Mars or other planets and the blue planet — Earth?

BJ: When I talk to people about space, it’s universal: the people want to take that journey of exploration. We won’t be able to do it now, we are taking the baby steps towards understanding what it takes to land on these other bodies, what it takes to get humans up there.

VB: What is the role of private-public partnership in your field?

BC: When you look at what we need to do to gain low-cost access to space, if we want to go somewhere like Mars, colonize Mars, extend our human presence throughout the solar system, we’re going to need to get much lower cost access to space. One of the great things that we’ve seen through our collaboration with the private industry and the commercial space program is that lower cost access to the space station is achieved through such public-private partnerships. We really need to extend that model, in order to really gain access to space — low cost access to space is what we will enable us to carry out the rest of our exploration.”

VB: What about communication with and identification of other forms of life?

BC: Ultimately, we want to find a common language, about exploration, find a common ground. We want to tell them we’re intelligent beings as well.

Benjamin Cichy is on Twitter but says he tweets less than Curiosity Rover (@MarsCuriosity), but you may still want to follow him: @BenCichy

Interview by contributor Liva Judic; Photo: NASA

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More