This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Note: This article contains spoilers for the Silent Hill series, particularly Silent Hill 3, which is almost impossible to talk about without spoiling. You’ve been warned.

Silent Hill: Downpour — the eighth game in the horror series that defines “brown trouser time” — had no save points. Instead, it autosaved for you. I’m normally not a fan of save points in horror games, where artificial, mood-breaking reminders that you’re playing a game are especially out of place. But when they were gone in Silent Hill, I missed them. The save points in this series aren’t just places to breathe easy and decide whether you’re too scared to go to sleep yet. Each of them says something about the themes of that particular game or gives insight into its protagonist.

The original Silent Hill had red notepads scattered around town for you to save on, which made sense because that game’s hero, Harry Mason, was a writer. “Someday, someone may experience these bizarre events,” he says the first time you find a notepad in an abandoned diner. “Hopefully, they will find my notes useful.” How thoughtful of him to jot down a quick memo about his progress whenever he has a chance — in between scouring the town for his lost daughter and one more box of pistol ammo.

In games like this, you’re constantly finding diaries or letters in which some poor doomed soul overuses exclamation marks while warning anyone reading of the horrors ahead. Silent Hill let you be that tragic fool, and every time I reload at one of those save points, I imagine Harry adding to his notes. “By the way, don’t use melee weapons on the flying monsters,” he might write, along with, “A kindly hobo has left health drinks on the benches at the end of these alleys.”

It’s the second game that really does something with the save points, though. In Silent Hill 2, you play James Sunderland, a widower who has been lured to the town by a letter seemingly written by his dead wife, Mary. That letter invites him to meet her in Silent Hill, where (among other things) he encounters squarish, vividly red objects on the walls that make his head hurt. These are the save points, but James’s complaint on seeing the first — “like someone’s groping around inside my skull” — suggests they may not be good for him.

What makes Silent Hill 2 the most beloved game in the series — and one of the most beloved horror games ever made — is the way it combines scary monsters and locations with the kind of psychological horror rarely seen in video games. The town is a place of fog and darkness, where creatures are audible before they’re seen, scraping and shuffling toward you, their wrongness so palpable and unreal that it makes your radio emit static and your screen blur with noise effects. When they do become visible, they almost seem human. Some look like people in straitjackets — others like nurses. Even the infamous Pyramid Head looks human up to the neck, his face hidden by a rust-red rectangular cone that looks like a torture device and seems to cause him pain even as he lumbers around tormenting James. As creatures emerge from fog and darkness, more details emerge — missing features, backward faces — and you see their monstrosity. As the story’s twists and revelations build, we learn more about James as well.

Meanwhile, something is disappearing.

The first save point you find is tilted at a 45-degree angle, as is one of the items in your inventory. It’s of identical shape, only pure white instead of red: the envelope in which you carry the late Mary’s ghostly letter. You can take that letter out of the envelope and examine it whenever you want a reminder of why you came to Silent Hill, but as you learn more of the truth, that letter fades. Later, the envelope vanishes from your inventory altogether. It doesn’t exist and never did — it was only real inside your head.

Eventually, you encounter nine of those pillow-shaped save point rectangles arranged together in one larger rectangle. This is the final save before your confrontation with Pyramid Head, where you learn one of Silent Hill 2’s horrible truths: how much you’re like the gore-soaked executioner, your face inching closer to the rectangular base of your own red helmet of torment.

In Silent Hill 3, the developers exchanged that rich but subtle symbolism for save points that are literal symbols called the Halo of the Sun. It’s a mark of the cult that’s behind many of Silent Hill’s transgressions — a group called the Order (though I prefer the more colorful name they use when posing as a charity organization: “The Silent Hill Smile Support Society”). The Halo of the Sun is a set of concentric red circles, filled with mystical icons and letters in Old Hungarian and Elder Futhark, the oldest of the runic alphabets, and all topped with a staring eye.

Heather Mason, the teenage protagonist of Silent Hill 3, does not like her save points. They look familiar, but they make her head hurt. Like James, an uncomfortable truth is waiting for her in that symbol.

Some of the Old Hungarian spells out the name “Alessa,” who those familiar with the first game will remember as the Order’s chosen child, destined to give birth to their dark god. The Halo of the Sun is also a symbol of rebirth, we’re told in the game — a cycle of life and death. (If you’re as bad at playing it as me, you’ll see Heather reborn at those save points often.)

The twist of Silent Hill 3 is that Heather is Alessa reborn. The aches and pains she feels throughout the game are spiritual contractions because, like Alessa, she’s destined to give birth to their god, and it won’t be a beautiful experience that leaves her smiling and cradling an infant.

It will be red.

With Silent Hill 4: The Room, we come to the conclusion of original designer Team Silent’s run on the series. Fittingly, the save point looks back to their beginning. Once again it’s a notepad, but this time only one instead of a collection placed around the town. Henry Townshend, trapped in his apartment and only able to escape in interludes, brings back scraps of paper that he keeps in that pad. They’re his only proof that he’s not going mad.

Like Harry from the first game, Henry is one of the rare Silent Hill protagonists without a secret past to uncover. Silent Hill isn’t trying to tell Henry something by tearing at his subconscious; instead, he’s the one recording proof so that he can share his experience with others.

Silent Hill: Origins and Homecoming were both made by new developers, and both had plots involving the Order. Both also have save points that resemble the Halo of the Sun, only diminished. In Origins, the eye from its top is placed within a triangle like the Eye of Providence familiar from U.S. currency; in Homecoming, the central circles are repeated without the text. They’re unfortunately apt symbols for games that shrink and simplify the motifs of the earlier ones. There was little of the layering that turned the best Silent Hill games into complex constructs of themes that fans enjoy analyzing and overanalyzing (which I’m certainly guilty of).

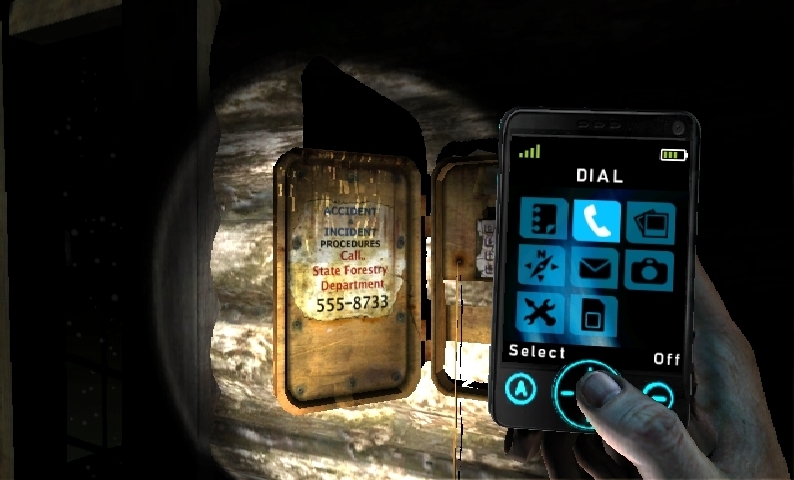

The next was Shattered Memories, a reimagining of the first that took the idea of a father searching a creepy town for his daughter and went in a new direction with it. The most interesting of the recent Silent Hill games, it departed from the series in many ways. An absence of symbolic save points was one of them — this Harry uses his phone to save rather than notepads or occult sigils.

But that phone had deeper significance. It reacted to the supernatural, emitting a rising, chiming buzz around things that shouldn’t exist. The phone’s camera could photograph objects and people that weren’t actually there, and after the crescendo of each encounter, receive text messages and voice mail from people Harry didn’t know. Some of them detailed events that hadn’t happened yet.

The Harry of Shattered Memories is confused by the car accident that opens the game. He’s not even sure of his own address until he sees it on his ID, and he’s uncertain how much time has passed and whether he’s seeing glimpses of the future or the past — whether some of these events and echoes are imaginings and if they’re even his own. His phone is the notepad that records his story in grainy photos rather than on scraps of paper, but it’s also trying to communicate the truth of his situation. It’s trying to provide him the fragments of his shattered memories as if it’s showing him — and the player — that all the pieces of the puzzle are right here if only you’d put them together.

It’s as if every time you ask it to save, it replies, “Save yourself.”