This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

Anna Anthropy’s book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Dropouts, Queers, Housewives and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form has my favorite definition of the word “game.” She succinctly defines a game as an “experience created by rules,” which is broad enough that it encompasses everything from something traditional like Mario to something more experimental like Dear Esther. In that same book, Anthropy writes that she “likes the idea of games as zines, as transmissions of ideas and culture from person to person,” and that the industry is incapable of creating a variety of perspectives due the market’s demand for formulaic games.

I’ve been mulling over Anthropy’s words in my mind for the last two months as I’ve played a multitude of both triple-A games and smaller, more personal ones created by independent developers. I want to focus on two such titles that share thematic elements — namely the bleakness of cubicle culture and the struggle against it by that culture’s “prisoners.”

Let’s work backward, shall we?

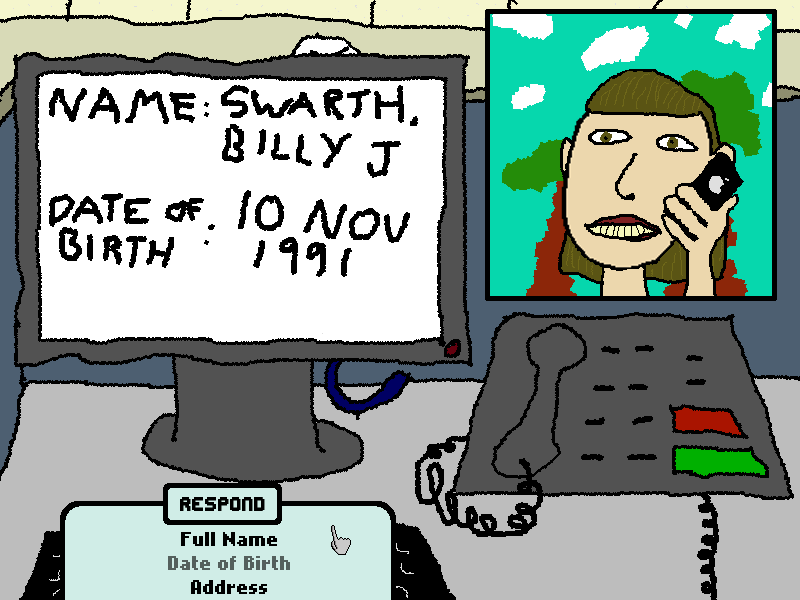

The most recent of the two is David S. Gallant’s I Get This Call Every Day, which has caused a bit of stir because of Gallant’s dismissal from his job over the game. Let’s try and get past that and examine IGTCED on its own terms — if such a thing is possible. To put it simply, IGTCED is a simulated experience of Gallant’s job at a customer service call center. An important distinction here: We’re not playing a suffering everyman cracking under the pressure of his job. We’re simulating Gallant (voiced by the man himself) or at least one of several possible Gallants as he takes a call from Billy J. Swarth, a stupid and irate customer.

The entire game is a fatalistic choose-your-own adventure confined to a poorly illustrated cubicle. No, really; this is one ugly game. But the unattractiveness makes sense. Offices are usually ugly places, and not just aesthetically, either. They often house surly employees performing the same menial, repetitious tasks week after week in order to make a living. Hardly a paradise.

A single playthrough of IGTCED can end rather quickly. If you try to rush through the phone call, chances are that you’ll receive an email from your eavesdropping boss informing you that you’re fired for breaking security protocol by accepting a short answer from Swarth (his first name) when a long answer (his whole name) was required. In fact, the best outcome you can hope for is for you to keep your job and have Swarth to call you a “fuckin’ asshole.” (At least, that’s the “best” one I earned.)

The “everyday” in the title — along with the (hollow) victory scenario — seems to suggest that this is a vicious cycle without end, a Sisyphean task. So does that mean that the “losing” conditions are actually the best ones since they mark an end to the unbearable labor? Perhaps, but we’re not privy to what happens after the credits roll. Our dismissed Gallant might find work at another tedious job — once again initiating the task of rolling that stone up the hill — or could find peace working as a successful game developer and critic.

Even so, Gallant’s dismissal from his job is still presented as a negative consequence of whatever action the player takes and understandably so. The traditional satirical jab at office jobs, after all, is that they’re what keep our bodies alive (via a paycheck) while killing our souls. Films like Office Space have played up this notion for the sake of creating humor, but Gallant’s piece stays firmly entrenched in a bleak “to hell with this” territory. And it’s ultimately to the game’s credit that it never strays from that vision.

IGTCED isn’t a fun game, but it’s one worth experiencing and is important as far as games charting personal experiences go. But it’s not the first one to combine the Sisyphean task and cubicle culture. Paolo Pedercini’s 2009 flash game Every Day the Same Dream features a faceless male protagonist who’s ostensibly growing weary of the same day-in, day-out motions of waking up, getting dressed, telling his wife goodbye, and then going to work. The game itself doesn’t center wholly around his employment at an office as the “plot” is that our protagonist realizes that he’s performing the Sisyphean task not just in his job but in nearly every facet of his life. The character momentarily breaks away from that cycle by embracing nature and interacting with other people besides his wife and co-workers. Where that realization leads to, though, is anyone’s guess.

The beauty of Every Day the Same Dream is its perplexing ambiguity. The penultimate scene features our protagonist — after being fired from his job — leaping from the roof of his office building to his apparent demise. But is he dead? The final section shows the character waking up again in his room and walking through all the stages of his day — except this time, no one is around. When he gets to the roof of his office, he watches another man — or it himself? — leap to his death, thus throwing a wrench into any straightforward analysis of the game. Is it the eponymous dream? Perhaps this some sort of purgatory where the protagonist is forced to relive his former life over and over. Endless interpretations abound, but I do know that whatever Every Day the Same Dream’s point seems to be, it’s not a happy one. A liberating one, maybe, but far from cheery.

But fun isn’t the objective when it comes to these games, is it? But games they remain — at least by Anthropy’s definition — and to be frank, I yearn for more of these experiences in the same way that I desire introspective, heart wrenching, and deeply personal movies like Tree of Life and The 400 Blows.

In comparison to cinema and literature, games are ever so slowly emerging from an adolescence marked by misogyny and a fiercely marketed lust for virtual bloodshed. Despite all the recent shaming of gaming culture by both those within the culture and those on outside looking in, nearly every week, new ad fascinating games showcase the potential of this medium that are funny, weird, tragic, introspective, abstract, concrete, minimalist, visually rich, poetic, and trashy — and they’re all at our fingertips. And here’s the kicker: A lot of them are free or at least cheaper than a value menu cheeseburger.

In fact, I’ll leave you with a number of those free titles. If you want to see where games are going thanks to the release of relatively inexpensive creation tools and some passionate developers, this is your chance.

Dys4ia (Anna Anthropy)

Octodad (Young Horses, Inc).

Unmanned (Molleindustria)

Mainichi (Mattie Brice)

The Stanley Parable (Davey Wreden)

One Chance (AwkwardSilenceGames)

The Majesty of Colors (GregoryWeir)