In developer Haemimont Games’ hybrid city management sim/squad-level tactics game Omerta: City of Gangsters, the sound of a swingin’ brass section fills the rain-drenched streets of this section of Atlantic City. It’s the roarin’ ’20s, and Prohibition is in full force. I’m fresh off the boat from the old country, looking to make a name for myself. I’m gonna be a big shot one day, you’ll see.

I start out small. I raid illegal breweries and distilleries for their illicit booze. I look for jobs to move these items and put a little scratch in my pocket, get a gang together, and build a criminal empire.

Let me introduce you to my crew. This here is Squigs; he’s a standup guy who knows a thing or two about robbing a place blind. Daredevil is my muscle; don’t let that French accent fool ya, she’s a bearcat. Doc is always out on the roof, but he’ll fix ya up in the heat of battle in no time flat.

I set up underground boxing arenas, Ponzi schemes, “pizzerias,” and other joints around the city. I hire accountants and build pharmacies and more reputable-sounding businesses to launder that dirty cash and erect night clubs and hotels and even get ourselves a legal team for when the Feds get a little too close.

And when they do, I’m right alongside my crew when things heat up. For every break into a police armory, every bank heist, and every skirmish with a couple o’ goons, I make sure the job gets done cleanly and quietly. With Tommy guns, that is.

What You’ll Like

Becoming the uncontested boss of Atlantic City ain’t gonna be a simple walk in the park. I have criminal networks to build. I have offers that can’t be refused. We got a lotta work to do.

Whackin’ ain’t never been such a savvy blend of old and new

I’ve got my hands full filling wise guys, grifters, muggers, gangsters, enforcers, and other shady characters from the underbelly of society with daylight in turn-based battles. Unlike Firaxis’ approach in the recent XCOM: Enemy Unknown, Haemimont doesn’t completely reinvent squad-level tactical combat but instead builds on past design philosophies.

I’m working with a classic points-based system, but that’s split into separate action and movement categories. This gives me a little more fidelity in where I can position members of my crew and what actions I want them to execute. And it enables my characters to interrupt an order upon discovering a thug, giving me a chance to provide new direction if need be.

Initiating most actions will forfeit any leftover movement points, too, still forcing me to make permanent decisions and face the consequences. Haemimont’s found a nice balance between the traditional time-units system and XCOM’s more recent approach.

Another noticeable improvement is the adoption of sticky-cover notifications that appear when I hover my mouse behind walls, tables, pillars, boxes, and other such things. Haemimont has simplified the system so that my characters are in cover or they aren’t, and my gang will helpfully lean up against walls or take ducking positions behind smaller objects as a visual indicator. Cover is destructible, too, keeping firefights dynamic.

The biggest change, though, is how Haemimont has redesigned turns. Typically, turns are divided between player and A.I. — I move all my characters, then the A.I. moves all enemies. Omerta instead gives each individual on the battlefield a turn and places them all in an order based on certain stats and perks. When I hit “end turn,” I’m only ending the turn for that character, not my whole crew. This sort of asymmetric system helps solve the first-move advantage inherent in the traditional “I go, you go” approach of many turn-based games.

That’s a nice place ya got … would be a shame if sumptin’ were to happen to it

Do I want to be a ruthless, cutthroat mobster who raids breweries, shoots up distilleries, firebombs hotels, and runs protection rackets? Or do I want to use my cunning charm to win by setting up soup kitchens, selling brand-name alcohol, and tricking people into investing in my Ponzi schemes? Or maybe I want it all.

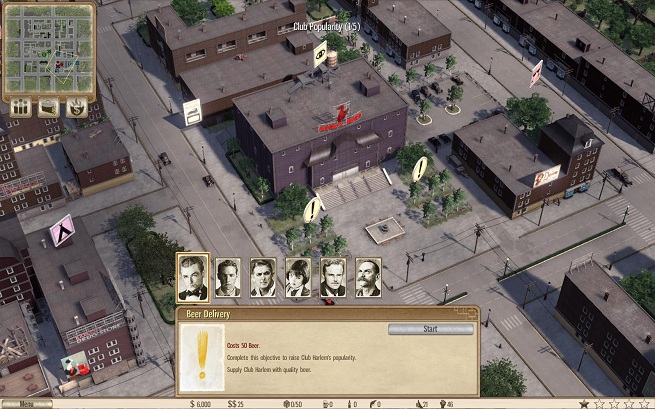

When I’m not filling rivals with lead, I oversee all operations in a district of Atlantic City, depending on the current campaign mission. I set up illegal businesses to rake in dirty dough and construct upright establishments to bring in clean cash. Using these resources as well as my stashes of beer, liquor, and firearms, I increase my influence through the Liked and Feared ratings, which impact the effectiveness of many buildings.

Creating such an empire will eventually provide the resources necessary to complete my goals, which could be generating a certain amount of scratch, raiding a Ku Klux Klan headquarters and killing the Grandmaster, or helping a talented young singer make her nightclub the talk of the town. My objectives are varied throughout the campaign, and I have so many ways to accomplish them that I feel free to approach these obstacles however I want.

For instance, all of my activities generate heat. When it gets hot enough, the police start an investigation. This represents a silent countdown, and if it reaches zero, I’ll be thrown in the can for good.

To manage this, I look for jobs around town to see if any crooked cops are willing to drop my heat for a little bit of cash. I bribe deputies to call in favors that cancel the investigation. I outright bribe the investigators themselves for a significant and continually more expensive amount of spinach. I scapegoat another criminal business in town. And, as a last resort, I might have to raid the station myself and destroy the evidence!

We ain’t no ringers in this town … this is the real deal

The number of approaches to dealing with heat is just one example of how Haemimont has run a fine-toothed comb through the entire game.

In the turn-based battles, weapons not only do base damage, but they can also inflict status ailments (like bleeding, vulnerability, or crippled), reduce courage, or provide support for teammates. Each of my gangsters have their own set of talents — special abilities like being able to set a booby trap or revive a fallen comrade — that add to those tactical options.

A lot of different scenarios can play out during a fight, too. During an escape mission, I had to leave a downed crew member behind. The coppers arrested him and took him to the pen, which meant that I had to jailbreak that poor sucker out. Another time, I stumbled upon a bunch of goons robbing the very same bank I showed up to heist, which forced me into a three-way shootout for the vault.

My crew is a tough bunch of characters: They can’t die, but if they eat lead, they will suffer a wound — like a broken leg, a gouged eye, or a concussion — all of which leave lasting negative effects until some time passes. So I still have to somewhat (more on that later) keep in the consequences of poor tactical orders in mind.

And as I build my empire, I’m not just limited to racketeering. I can bribe a crooked cop if I need a powerful weapon to give my crew. I can throw a party for a celebrity to increase my Liked rating around town and convince him to launder some of my money; I can undertake wet work jobs from a local crime lord; I can bribe a politician to release a gangster from the big house if I don’t want to get my hands dirty.