The pioneers of Silicon Valley gathered for a rare reception last night for the debut of a film about them. The film is a rare documentary with the highest production values, featuring the real revolutionaries who changed the world (as opposed to the silly kids from Bravo’s Start-ups: Silicon Valley reality TV show).

The documentary, Silicon Valley: Where the Future Was Born, will run on TV as part of PBS’s American Experience history series. Some of the luminaries gathered at the event were Gordon Moore (above right), co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel; Andy Grove (above left), former chief executive of Intel; Arthur Rock, the venture capitalist who funded Intel; marketing wizard Regis McKenna; Les Vadasz, the earliest employee at Intel; and Ted Hoff (below left) and Federico Faggin (right), co-inventors of the first microprocessor.

The film chronicles the formation of the semiconductor industry in the 1950s and 1960s in Santa Clara County, the region from Palo Alto to San Jose that became the heart of Silicon Valley and a regional technology ecosystem that spans nine counties in the San Francisco Bay Area. The film airs on PBS at 8 pm on Tuesday Feb. 5.

Hari Sreenivasan, a host at the PBS News Hour, hosted the event and invited the pioneers on stage at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif. The museum and Intel hosted the event, but the film was fair enough to include all of the pioneers from rival companies, including Charlie Sporck, longtime chief of National Semiconductor, and Jerry Sanders, founder of Intel arch rival Advanced Micro Devices. All of the companies grew up in the same region and became multinational juggernauts of the electronic age. But many also faltered and died along the way.

Mark Samels, executive producer of the American Experience, said in front of the crowd, “It’s sort of like doing a film on the founding fathers with Adams and Jefferson in the room.”

For me, it was a reminder of what is great about Silicon Valley, where the founding pioneers are still living among us.

The film tries to convey the “sense of possibilities, the risk taking, and the moment in time that allowed Silicon Valley to happen,” said Randy Maclowry, director of the film.

I walked around the reception and snapped pictures of the people who were responsible for the beginnings all of the devices that we now take for granted. My kids don’t even know this ancient history, so the film, narrated by authors Michael S. Malone and Leslie Berlin, comes at an important time. It captures history before those who made it have all passed away.

Bob Noyce, the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, died in 1990. But he is very much the central figure of the film. He founded Fairchild with the “traitorous eight” defectors who left William Shockley’s Shockley Laboratories. Shockley won the Nobel Prize for co-inventing the transistor, but he became increasingly “erratic.” So Noyce led the team (pictured below, with Noyce in front) to start Fairchild.

Fairchild was in the right place at the right time. In 1957, the Russians scared America with the launch of the first satellite, Sputnik. President Eisenhower created NASA within the next year and launched the American space program. Fairchild was positioned to make the chips that would go into the rockets and space ships.

But first, the team had to create working chips. Noyce was so charismatic that he landed a contract with IBM, promising to deliver 100 chip prototypes to them — even though those chips hadn’t been designed yet. Texas Instruments gave Fairchild some serious competition, stunning them with a patent for the “integrated circuit,” which packed together transistors and other components in an electronic system in a single chip. But Noyce and Jean Hoerni created designs that made the integrated circuit practical. The companies came to blows in court over the invention, but it was settled after a decade. By that time, TI was using Hoerni’s planar process to manufacture integrated circuits.

In contrast to Shockley’s dictatorship, Noyce and co-founder Gordon Moore gave out stock options and managed in a way that was more egalitarian, building a company based on meritocracy. They infused this egalitarianism in the rest of the Valley, which came to be a collection of many companies that spun out of Fairchild. Noyce and Moore, fed up with the East Coast management of Fairchild, spun out themselves, forming Intel in 1968.

Moore and Noyce were brilliant at science and management, but Intel’s task master was Andy Grove, who got the operations working to churn out chips in highly specialized factories. He instilled some serious, military-style discipline that included “late lists” for those who showed up late in the morning. Intel created cutting edge chips that helped make Silicon Valley the world leader in electronics. The work included the designs of Federico Faggin and Ted Hoff, inventors of the 4004, Intel’s first microprocessor, which hit the market in 1971. The chip had 2,300 transistors. Decades later, chip makers like Intel can put multiple billions of transistors on a chip. That is why we can access Facebook at blazing speeds from mobile devices.

The film footage includes women who were on the assembly line, like Ginger Jenkins, who had the dexterity to assemble chips with tiny wires. But the 1950s-era Silicon Valley was a place where men ruled the companies and gathered at bars such as Walker’s Wagon Wheel. They traded tips over drinks, and the Valley quickly became a place where there were few real secrets.

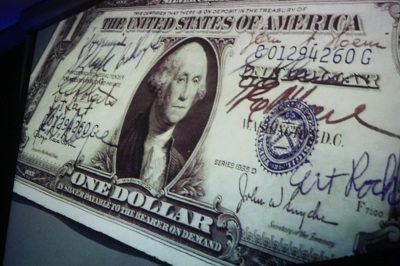

The film starts with the Shockley defectors, who gathered at the Clift Hotel in San Francisco for a meal. They were ready to follow the charismatic Noyce, a brilliant scientist and a Pied Piper for talent. They signed their names on dollar bills (pictured right) to seal their contract.

If Noyce was the father of Silicon Valley — alongside David Packard and Bill Hewlett — then the “Fairchildren” were the ones who scattered to the winds and created the startup culture that became the Valley that’s famous around the world today.

Ann Bowers, Noyce’s widow, said the egalitarian attitude came from Noyce’s belief that you should respect people. She recalled how Noyce often talked late into the night with the young Steve Jobs as he was starting Apple. If Noyce were alive today, Bowers said, he would have been very interested in all of the medical devices chips are enabling.

“I can’t imagine Bob tweeting,” she said.