Ann Bowers knew Bob Noyce, the “mayor of Silicon Valley,” better than anyone. She was married to the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel, and witnessed the magnetic effect he had on the people who followed him to the region that will be chronicled in an American Experience history documentary on PBS on Tuesday (Feb. 5) at 8 pm. The film is called Silicon Valley: Where the Future Was Born, and it captures the people like Noyce, who died in 1990, and how they made such a mark that their impact is still reverberating today.

Last week, Bowers (pictured right) spoke about Noyce on stage at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., where the surviving pioneers of Silicon Valley gathered to celebrate the film and the man at the center of it. The event was a chance to hear about the living history of the technology era from some of the people who created it. Bowers tried to convey what it was like to be in the same room with Noyce, who had a magnetic personality. At the same time, he wasn’t a taskmaster and had to bring in Andy Grove, later the legendary CEO of Intel, to keep order.

Last week, Bowers (pictured right) spoke about Noyce on stage at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif., where the surviving pioneers of Silicon Valley gathered to celebrate the film and the man at the center of it. The event was a chance to hear about the living history of the technology era from some of the people who created it. Bowers tried to convey what it was like to be in the same room with Noyce, who had a magnetic personality. At the same time, he wasn’t a taskmaster and had to bring in Andy Grove, later the legendary CEO of Intel, to keep order.

Noyce isn’t depicted as some superhero, since he had his flaws. But, like David Packard and Bill Hewlett before him, he was a very big part of the fuel that set the valley on fire. To grow like it did, Silicon Valley need a visionary like Noyce, a researcher-like co-founder Gordon Moore, and a tough guy like Grove — they were all there at the critical time. Noyce’s efforts shaped the technology, business, money, politics, and culture of Silicon Valley. Bowers brought Noyce down to the human level.

At the start of the event, host Hari Sreenivasan asked Bowers about the many talents of Noyce. He played the oboe. He was the state diving champion. He lettered on the swim team. He was in the drama club. And he knew more about transistors than just about anyone on the planet. Bowers smiled and answered a quick “yes” to each one of the facts.

“How is this possible, where did that confidence come from?” Sreenivasan asked.

“It’s important to understand the kind of family that Bob came from,” Bowers said. “His father was a congregation minister. There were four boys. They had very little by way of financial resources. But they had a lot of other resources. They were a tight family. They worked hard. Respected others. They were generous. And they took care of themselves. By their own effort. That was where a lot of Bob’s attitudes came from.”

Asked about Noyce’s “halo effect” and magnetism, Bowers laughed and said, “Well he did, obviously! He could project that from the podium. He seemed like he was talking directly at you. You might feel like he was talking to you and you were the only person in the room. He had that ability. He was listening. He was not talking at you. He was talking with you.”

![]() Noyce grew up in Grinnell, a small town in Iowa, in a world without electronics except for ham radios and the equipment used to operate a farm. While his father was religious, Noyce was an agnostic. He and the other migrants to California’s Santa Clara Valley shared “middle American values,” said Michael S. Malone, a longtime Silicon Valley author, speaking in the film.

Noyce grew up in Grinnell, a small town in Iowa, in a world without electronics except for ham radios and the equipment used to operate a farm. While his father was religious, Noyce was an agnostic. He and the other migrants to California’s Santa Clara Valley shared “middle American values,” said Michael S. Malone, a longtime Silicon Valley author, speaking in the film.

“They were honest, good as a handshake,” he said. “They were small town and masters of the universe. That tension drove these guys on.”

The film tries to convey the “sense of possibilities, the risk taking, and the moment in time that allowed Silicon Valley to happen,” said Randy Maclowry (pictured left, on far left), director of the film. “They found themselves at the right place and the right time, and they had the technological chops and understanding of what was possible to take the risks.”

Noyce had migrated to the Santa Clara Valley to work for William Shockley, the Nobel-prize winning physicist who co-invented the transistor and moved West to Palo Alto, Calif., to set up Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory — and be near his mother.

But Noyce, Gordon Moore, and six other colleagues broke away, since they didn’t like his erratic behavior. They were deemed “the traitorous eight” (pictured right) by Shockley. They founded Fairchild Semiconductor, a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument.

But Noyce, Gordon Moore, and six other colleagues broke away, since they didn’t like his erratic behavior. They were deemed “the traitorous eight” (pictured right) by Shockley. They founded Fairchild Semiconductor, a division of Fairchild Camera and Instrument.

In 1957, the Russians scared America with the launch of the first satellite, Sputnik. President Eisenhower created NASA within the next year and launched the American space program.

Noyce’s team at Fairchild was positioned to make the chips that would go into the rockets and space ships. The federal government had an “insatiable need” for what Fairchild would produce, said Leslie Berlin, author of The Man Behind the Microchip: Robert Noyce and the Invention of Silicon Valley.

But first, the team had to create working chips. Noyce was so charismatic that he landed a contract with IBM, promising to deliver 100 transistor prototypes to them — even though those chips hadn’t been designed yet. Within five months, they created the chips and delivered them to IBM in a Brillo soap box.

Texas Instruments gave Fairchild some serious competition, stunning them with a patent for the “integrated circuit,” which packed together transistors and other components in an electronic system in a single chip. TI’s Jack Kilby created a prototype first, but it was cobbled together with wires, and that wouldn’t have been practical for mass production, said Jerry Sanders, founder of Advanced Micro Devices and then a salesman at Fairchild.

Noyce, who had scribbled an idea in a notebook before Kilby, and Jean Hoerni created designs that made the integrated circuit practical. Jay Last was tasked with making Fairchild’s working integrated circuits, which are the foundation of microprocessors and all chips manufactured today. Fairchild and TI got into a 10-year legal war over the patent on the integrated circuit. At the end, they shared credit, and TI used Hoerni’s “planar process” for making chips.

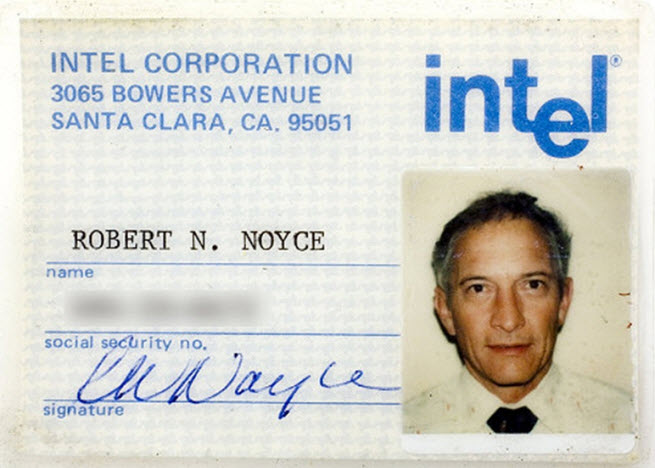

In contrast to Shockley’s dictatorship and the East Coast profit-milking of Fairchild’s parent company, Noyce and co-founder Gordon Moore founded Intel in 1968 and gave out stock options. They managed in a way that was more egalitarian, building a company based on meritocracy. Bowers gave credit for that culture to Moore as well as Noyce. They infused this egalitarianism in the rest of the Valley, which came to be a collection of many companies that spun out of Fairchild. Today’s valley is littered with descendants, or Fairchildren, such as Advanced Micro Devices.

In contrast to Shockley’s dictatorship and the East Coast profit-milking of Fairchild’s parent company, Noyce and co-founder Gordon Moore founded Intel in 1968 and gave out stock options. They managed in a way that was more egalitarian, building a company based on meritocracy. Bowers gave credit for that culture to Moore as well as Noyce. They infused this egalitarianism in the rest of the Valley, which came to be a collection of many companies that spun out of Fairchild. Today’s valley is littered with descendants, or Fairchildren, such as Advanced Micro Devices.

Noyce once said that the stock option money didn’t seem real.

“It’s just a way of keeping score,” he said.

The Pied Piper of his generation, Noyce counseled his employees to “go off and do something wonderful.”

Asked what Noyce would have thought about technology today, Bowers said he would have appreciated all of the access to information that we have today with the internet.

Bowers arrived at Intel in January, 1970.

“What was so profound about Bob and Intel was the sense that it was all about a challenge and discovery,” she said. “It wasn’t about making a lot of money or having a lot of power. You see challenges, and you see opportunities.”

Noyce was married to Elizabeth Bottomly in 1953, but they were divorced. Noyce and Bowers got married in 1974. Bowers introduced Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple, to Noyce. Jobs was looking around for a mentor. He hit it off with Noyce, and they talked about all sorts of ideas. Bowers found Jobs to be “extremely annoying because he was so self-centered.” She said Jobs’ parents didn’t seem to know what to do with him because he was a genius who needed someone to talk to.

“They would talk about almost anything,” Bowers said.

Noyce wasn’t a follow-through guy, and he wasn’t good at being tough on people. That was why Noyce and Moore brought in Andy Grove, Bowers said.

Bowers drew the biggest laugh of the evening when she said, “I can’t imagine Bob tweeting.”

Noyce loved cars and the most modern cameras. He felt a lot of the things he was interested in were made better by the integrated circuits he created. He was proud that chips formed the heart of a personal computer, which was an “everyman’s tool.”

Bowers held jobs such as director of personnel for Intel, and she was the first vice president of human resources for Apple. She currently serves as the chair of the Noyce Foundation.

By the end of his career, Noyce had organized efforts such as the Semiconductor Industry Association and Sematech to ensure that U.S., which was in stiff competition with Japan, was able to hold on to its technological edge, educate its next generation of engineers, and make sure that semiconductor jobs stayed in the country. While nations such as China, Korea, and Japan have risen on the global stage, the United States is still the largest country in terms of market share in the chip business in the world. You can thank Noyce for a lot of that, and you shouldn’t miss this film.

Here’s a snippet of the video of Ann Bowers on stage with Hari Sreenivasan, a host of the PBS News Hour.

[vimeo http://www.vimeo.com/58605848 w=500&h=281]