LAS VEGAS — David Cage scolded the game industry for making the same games over and over and urged the game industry to grow up.

LAS VEGAS — David Cage scolded the game industry for making the same games over and over and urged the game industry to grow up.

Cage, the chief exec of movie-like game developer Quantic Dream (the makers of alternative titles such as Indigo Prophecy and Heavy Rain), is making an ambitious game dubbed Beyond: Two Souls, which received accolades last year at the E3 game trade show. He gave a talk at the DICE Summit about the “Peter Pan syndrome,” or how the game industry’s refusal to grow up as other industries have.

Cage, the chief exec of movie-like game developer Quantic Dream (the makers of alternative titles such as Indigo Prophecy and Heavy Rain), is making an ambitious game dubbed Beyond: Two Souls, which received accolades last year at the E3 game trade show. He gave a talk at the DICE Summit about the “Peter Pan syndrome,” or how the game industry’s refusal to grow up as other industries have.

“The ‘Peter Pan syndrome’ describes a person who is socially immature and anxious at the idea of becoming an adult,” he said. “They refuse to grow up.”

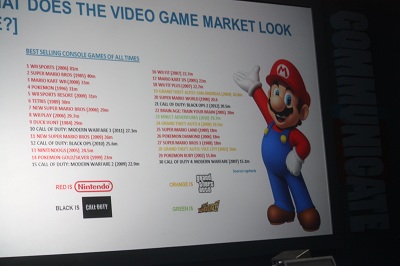

As evidence for this, Cage pointed to the list of the 30 best-selling games of all time. Nintendo had 21 of these, such as Super Mario Bros., mostly directed at kids. The Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto series accounted for a number of the game on the list. And the lone casual title was Kinect Adventures.

This means that the winning genres are kids, casual, and violent action games.

If you compare the 1992 game Wolfenstein 3D to Call of Duty: Black Ops II in 2012, you see the tremendous evolution of realistic graphics. But the games, he said, are pretty much the same.

“You kill people before they kill you,” Cage said. “We use the same paradigms. You master this system to beat the computer or your friends. Same worlds. Same games. No surprise, we have the same audience.”

Cage said the game industry should change because the landscape is changing quickly, with big changes in digital distribution that brings more competition. On top of that, the competition for entertainment time in a world of many platforms is getting even more fierce.

Cage’s prescription for the game industry follows.

Cage’s prescription for the game industry follows.

1. He said we have to make games for a wider audience.

2. Change our paradigms. “We cannot keep doing same games all the time,” he said. “Violence and platforms are not the only way. We have to decide that as an industry.” He added, “If the main character can’t hold a gun, designers don’t know what to do. How do I play?

3. Remember the importance of meaning. He asked, “What do we have to say?” He said games should address real-world themes like politics or homosexuality, should let authors in. All real-world themes should come into use.

“It will leave an imprint and keep you thinking about it after you have finished,” he said.

4. Become accessible. “Let’s focus on minds, not on thumbs,” he said. “Who cares how fast you can move your fingers?” He said the journey is important, not the challenge.

5. Bring other talent on board. Like filmmakers.

5. Bring other talent on board. Like filmmakers.

6. Establish new relationships with Hollywood. Games shouldn’t just be licensed products. “This is not the right way to build a relationship,” he said. “Games can be a respected medium now. Time has come for a constructive, balanced new partnership.”

7. Changing our relationship with censorship. “Sometimes I use violence, sometimes I use sex,” he said. “Now I have someone looking over my shoulder saying what you can’t do. If it is OK in a film, why is it not OK in a game?” The answer is games are “interactive” or geared toward kids. “As long as violence and sex are put in context, they should be fine,” he said. At the same time, he is shocked by games that try to one-up each other with increasing levels of violence. “We should stop doing this, because this is a matter of being responsible to ourselves and society,” he said. “If we don’t want to be accused of being responsible every time something terrible happens, we should be responsible.”

8. The role of the press should evolve from reviewers to critics. “Press are very clever people who analyze the industry,” he said. “On the other side of the spectrum, people give just scores. You have a camera bug and so you get a 5-out-of-10 [review score]. This is not press. Where is the analysis or thinking? Being a critic is a very serious job.”

9. The importance of gamers. When you buy games, he said, “You place a vote on where the future of games should go.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More