You don’t have to have college-level experience to write good poetry — just a video game that makes you think.

B.J. Best, an assistant professor at Carroll University in Waukesha, Wis., knows a thing or two about poetry. He’s published two books full of it called Birds of Wisconsin and State Sonnets. Unlike a lot of academics, he’s also gamer, and he even claims to have beaten Super Mario Bros. on a pontoon boat — with an actual television and Nintendo Entertainment System. This is probably a feat you could only attribute to him.

B.J. Best, an assistant professor at Carroll University in Waukesha, Wis., knows a thing or two about poetry. He’s published two books full of it called Birds of Wisconsin and State Sonnets. Unlike a lot of academics, he’s also gamer, and he even claims to have beaten Super Mario Bros. on a pontoon boat — with an actual television and Nintendo Entertainment System. This is probably a feat you could only attribute to him.

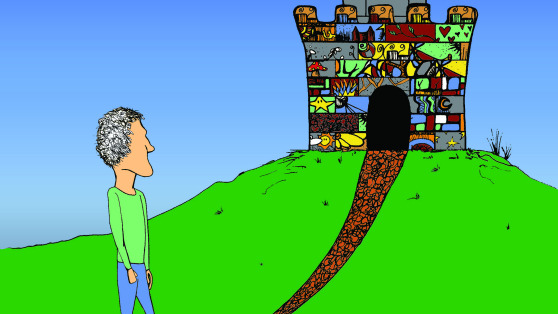

But Our Princess Is in Another Castle is Best’s third self-authored poetry book, which debuts in March for $14.95. These are prose poems, whose paragraph-style makes them even more accessible to general audiences. While they’re entirely about video games, they’re not full of gaming lingo. That can be hard to parse for readers who aren’t entrenched in the appropriate genres.

“For me, the critical idea is that the poems are not directly about the video games; rather, the games and their details provide points of departure for talking about other, nondigital aspects of life,” Best told GamesBeat, explaining why you could hear one of his poems and never guess that it was about a video game like Golden Axe or Asteroids. “As I was writing the book, I tried to remain very cognizant that many readers might not have played the particular game that inspired a poem, so I needed to make sure the poem still appealed to them. Those who know the games will find familiar details from them in the poems, but they’re usually included in brief, sidelong ways.”

Best chose to follow the adage “write what you know,” looking to classic video games rather than new ones since they better represent his ’80s childhood. As it happens, they’re a lot easier to write about, too.

“They’re much smaller, easier to conceptualize, and, frankly, weirder in a way that encourages exploration,” he said. “I think it’d be much harder to write about a contemporary first-person shooter, for example, because they’re very lifelike and so much of the story is given to you — it’d be hard for me to pick only the details I need and then make the material my own.”

The creative exercise of translating pixels to poetry shows that you can use any experience — even video games, which are often viewed as trivial entertainment — to discuss serious subjects, said Best. Because so many different types of people play them, we wondered how other people — those without teaching degrees, for example — could learn to write the way he does.

“My best advice is to take ownership of whatever details of the subject have energy for you, and then try as hard as possible to ignore the rest,” he said. “Video games are a great medium for this because they often have such an odd and incongruous set of details. Why is Pac-Man chased by ghosts but eats fruit? Why is Mario in a kingdom ruled by mushrooms that was invaded by turtles?

“A writer doesn’t owe any allegiance to fully or even accurately rendering the initial experience — what’s more important is using key details to talk about something more than just the surface subject.”

Those aren’t the only pointers you’ll need if you want to write “good” video game poetry, though. The basic tenets still apply, and that means making sure your poem contains strong details and imagery, compelling word choices, and a fresh perspective. Best recommends taking an initial observation and then developing it into something with more resonant meaning.

Those aren’t the only pointers you’ll need if you want to write “good” video game poetry, though. The basic tenets still apply, and that means making sure your poem contains strong details and imagery, compelling word choices, and a fresh perspective. Best recommends taking an initial observation and then developing it into something with more resonant meaning.

“Some video game poems fail, I think, because they take place entirely within the game world,” he said. “And since the poem takes place within the game, it usually just re-creates the experience of playing it. Those who haven’t played the game will likely be uninterested or lost, and those have played the game are already familiar with the experience. That poem is probably not doing enough to make the material new and interesting.”

So if you can accomplish that by writing about video games, does that make them art? Best told us that this book is outside that discussion — used for its own artistic intents, not those of the games’ — but that he thinks the debate is settled by now since all games involve artistic creation through graphics, sound, and other aspects.

Not even game is art, though, the same way that film can be art — communicating messages — but “major motion pictures” are only made to entertain.

“Both sides of this debate often argue in problematic ways,” said Best. “The ‘games are not art’ advocates are usually predictable, uninformed, and unwilling to seriously engage the topic; the ‘games are art’ folks often have a neurotic need to be accepted by the first group. I think developers and gamers should be pretty comfortable by now they’re working with an art form, and that the rest of the culture will eventually catch up. And, of course, it’s already catching up, with [the Museum of Modern Art’s] recent plan to house a video game collection as an example.”

Click on for excerpts and a name-that-game quiz.