[Editor’s note: We posted this story earlier this week but not many folks recognized its significance, so we’re republishing it now with more reaction].

Here’s your smart city, and it’s nowhere near Silicon Valley. The small town of Stratford in Ontario, Canada, about 90 miles from Toronto and two hours east of Detroit, is about to become one of the world’s first distributed data centers.

I’ll explain what that means in a moment. But it could be a remarkable technology achievement, conquering well-documented technical hurdles — made possible by a Silicon Valley startup called LeoNovus. This Sunnyvale, Calif.-based startup, run by seasoned entrepreneur Gordie Campbell, has figured out a way to tap the unused computing power spread around in our homes and offices. It harnesses that into a massive parallel computer that can effectively serve as a data center. Only this data center is distributed. It doesn’t require real estate, computing hardware, cooling, or electricity.

“This is a game changer that impacts multiple markets,” Campbell told VentureBeat in an exclusive interview.

If it works, it could prove to be a disruptive technology and a linchpin in creating a sustainable business model for technology, entertainment, and broadband companies. If it doesn’t, it will be a big crater.

But that’s the kind of risk that Campbell, who previously had big duds like QuickSilver Technologies and big hits like Chips and Technologies, likes to take. Creating better distributed data centers could be huge. Market researcher Gartner predicts that hardware spending in data centers will climb from $106.4 billion in 2012 to $126.2 billion in 2015.

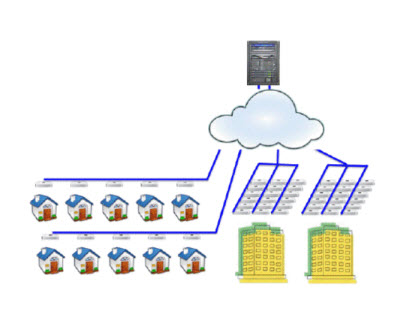

LeoNovus has licensed its technology from Sviral, a research and development company headed by Campbell. The idea is to exploit “Dark Cores” of the Internet. These are computing brains, or cores, that sit idle most of the time when we’re not using our multi-core PCs, set-top boxes, and any other connected computing devices.

LeoNovus has licensed its technology from Sviral, a research and development company headed by Campbell. The idea is to exploit “Dark Cores” of the Internet. These are computing brains, or cores, that sit idle most of the time when we’re not using our multi-core PCs, set-top boxes, and any other connected computing devices.

“The analogy is like harnessing the power of the sun and the wind for energy,” Campbell said. “One of our people had a breakthrough insight and we moved from there to productize it and take it to the market. You can sell your computing power back to the grid.”

The fundamental reason those resources are left idle is that computers haven’t been designed to tap each other when they need more power. Problems such as latency and programming complexity get in the way. But the LeoNovus team (including tech leaders Paul Master and Dan Willis) says it has figured out how to get all those computers working in tandem.

“People talk about cloud computing now, but all they’re doing is accessing a data center,” Campbell said. “We create a true cloud, where we push the computer out to the edge and create a true cloud. We could make something redundant in five different places, so Hurricane Sandy wouldn’t hurt it.” It’s like Scott McNealy’s saying at the old Sun Microsystems (a Silicon Valley computing giant that Oracle acquired): “The network is the computer.”

Nick Tredennick, a chip expert and an advisor to the company, said in an interview that the key question is whether LeoNovus and Sviral can truly solve the issue of programming a lot of cores at the same time.

“If they have that, then everything else falls into place,” he said. “It will be a matter of execution. But it is very exciting to watch.”

The town of Stratford, which pledged to become a tech-focused smart city years ago, is the test bed for LeoNovus. Mayor Dan Mathieson (pictured right) told VentureBeat he has a LeoNovus-enabled computer in his own home, and his town’s 32,000 residents will eventually all get free computers or set-top boxes so they can become the beta community for LeoNovus.

LeoNovus will partner with city-owned infrastructure company Rhyzone Networks, which has built a high-speed fiber-optic and Wi-Fi network for the town. That technology is a foundation for the company’s “intelligent community” initiatives, and it makes it much easier for LeoNovus to test its technology, which is in its third deployment trial. The company started deploying the technology this week, and a full rollout could begin anywhere from three to six months from now, Mathieson said.

[Update: The internet service provider (in this case, the city’s own Rhyzone) will bundle a “high performance gateway box” that runs a full access browser and TV service with apps. The hardware is scalable. There is no clarity yet on when all residents would have free hardware and service.]

By marshaling the unused compute cycles, the town benefits from having its own distributed data center that it doesn’t have to pay to maintain. LeoNovus or the town could give out free computers to its residents and give them free broadband as well, since the residents agree to let LeoNovus use the idle computer time for its own purposes. Consumers can use the PCs or set-tops to get on the web. Everybody benefits from this cloud-based revenue stream. Of course, if the town residents download porn 24 hours a day, it could be a problem. But given usual usage patterns, it should work.

Mathieson happened to meet Campbell and his team at the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) trade show a couple of years ago. Mathieson was hawking the town’s availability as a technology hub, and Campbell needed that to test his technologies.

The mayor said the strategy and the relationship with LeoNovus are paying off. Stratford was just selected as one of the top 7 Intelligent Communities for 2013. LeoNovus can run its software on any kind of device that the city deploys to its citizens. The city will benefit by getting a royalty payment of some kind from LeoNovus.

“I”m so impressed with what they are proposing to do,” Mathieson said. “I think it is a game changer. It helps our city meet the goal of digital literacy and universal access.”

Master, vice president of strategic technologies at LeoNovus, said the number of cores available is huge. In a typical home, he said there are 2,000 underutilized cores across various electronic devices. There are another 20,000 in a typical office, and 300 in a car. That’s a lot of dark silicon. There could be enough computer power available in Stratford alone to make its distributed data center into a top 500 supercomputer.

“If we fully utilize them, we can get more done,” said Master, who showed a working demo of the technology at the company’s headquarters.

Besides Stratford, LeoNovus is talking with a number of other possible test beds. Taiwan-based Leadtek has signed an agreement with LeoNovus to deploy a similar program to Stratford. Leadtek is building many of the LeoNovus software-enabled gateway boxes being deployed in Stratford. The company is also working with telecommunications companies and hotel operators. A hotel could monetize unused set-tops, dubbed “lazy assets,” to offer on-demand services at a lower cost.

It is a disruptive model in the same way that cloud-based gaming service OnLive runs games in a data center instead of on home PCs. But this trick is the opposite of that. The software runs across devices on the edge of the network, in homes and in offices.

LeoNovus shares (LTV) have been publicly traded on the TSX Venture Exchange since June 2009. Campbell calls the Dark Core Distributed Data Center the “D2C” opportunity. With the world’s data doubling every two years, users will create 1.8 trillion gigabytes of data this year. Facebook said a year ago that it was getting 3,000 pictures uploaded every second.

Nobody has thought about how to make use of cores like the LeoNovus team. Master and Campbell founded QuickSilver in 1998. They raised $84 million to create an adaptive computer with multicore chips in the days when Intel, the world’s biggest PC maker, was busy making single-core, single-brain microprocessors. But the killer problem was that no one in the software community understood how to program those cores. QuickSilver closed shop in 2005.

While that company failed and took down the technology with it, Campbell hopes that Sviral can license its technology to other companies like LeoNovus that can execute within certain applications, such as the distributed data center.

Multicore chips are available today, as Intel and Advanced Micro Devices adopted them more than five years after QuickSilver started talking about them. Multicore chips are more efficient at handling processing than single-core chips, which hit the wall on power consumption.

“We believed the world would go multicore in 1999, and now we have gone from desert to overabundance in the blink of an eye,” Campbell said.

While humans can multitask well, computers have to be taught to do it right. Software programmers still have to catch up, and few really understand how to make use of all the cores available to them. With Sviral and LeoNovus, the old QuickSilver team was rebuilt and refocused on new ideas that made multicore programming much easier. LeoNovus was incorporated in 2008. Its innovation is connecting cores in an efficient way.

Data centers have become the key to cloud computing and delivering the Internet to the masses. But data centers certainly need something to lower overall costs. Large data centers take a year to three years to plan and fully deploy. It takes a while to acquire land, build a center, comply with government policy and regulations, secure adequate bandwidth, deploy computing power and storage, and do so with a footprint that reduces carbon emissions.

It’s a bold plan, but Campbell has a history as an innovator. His companies have created $5 billion in market value over time, rising from early-stage concepts to huge companies. He was the first corporate marketing manager at Intel and left to start SEEQ Technology, a maker of the first Ethernet networking chips. Then he started Chips and Technologies, the world’s first “fabless” chip firm. Chips and Technologies enabled a whole fleet of PC clone makers. Campbell formed the venture firm Techfarm Ventures and invested in companies such as 3dfx Interactive, Cobalt Networks, HotRail, NetMind, Portal Player, and Resonate.

Master was a co-founder of QuickSilver and serves as chief technical officer at Techfarm Ventures. He has more than 40 patents issued or pending, and has been a pioneer in new fields of computing such as reconfigurable processor, software defined radio, and massively parallel processing. Darlene Kindler, who worked with Campbell at a number of other companies and also worked in the video game business at Sony and Adscape Media, heads marketing.

Dan Willis, chief architect, has 25 years of experience in distributed software and systems design. He previously worked at Google and Adscape Media. He also spent 15 years at Bell Northern Research and Northern Telecom. He has more than 60 patents and applications to his name.

[Update: Some of Sviral’s patents have been filed under the names of Master and Willis under the former corporate name, Personal Web Systems. Other patents are pending. Andy Wolfe, a technology consultant and inventor wondered if the boxes would use a lot of electricity if they are used more often, but LeoNovus said the electricity usage is “extremely minimal,” and the user always gets priority on usage. Rich Belgard, a chip patent expert, said he is skeptical, at least until he sees the patents.

“Most of the interesting problems that require this kind of massive parallelism require access to large datasets as well,” Wolfe said. “The challenge is getting all that data through the network to the homes. You have to allow everyone unlimited bandwidth so that it doesn’t come out of their Netflix-watching budget. One of the interesting parts of the idea is that you have to do it in Canada. It makes much more sense in places that don’t need air conditioning. Otherwise, there is a multiplier effect on the electricity costs.”]