NEW YORK — Foursquare CEO Dennis Crowley was on the defensive again today, responding yet again to the persistent misunderstanding that his company doesn’t know how it’s going to make money.

“A lot of folks think we aren’t generating revenue or that we don’t care about revenue. They’re wrong,” Crowley said on stage at TechCrunch Disrupt, a startup conference here, this morning. “This past March was our highest-generating revenue month so far. We expect to see that going forward.”

In summary: Foursquare is making money, but no one actually believes it.

Foursquare’s plight contrasts strongly with the success of shopping app Shopkick, which is pulling in cash in ways that most location-based mobile apps — including Foursquare — have so far been unable to. The app, which rewards people for shopping in certain stores, helped Shopkick’s partners make $200 million last year. More notably, it also allowed Shopkick to report its first profitable quarter late last year.

“It seems almost embarrassing to make money nowadays,” Shopkick CEO Cyriac Roeding told me.

While Shopkick’s brick-and-mortar focus means that it’s tied the physical world, most of its conceptual strength comes from the world of online advertising. Similar to the average Google search (which Google sells advertising space against) Shopkick is all about measuring intent: If you walk in a store and open up the app, chances are you’re looking to buy something.

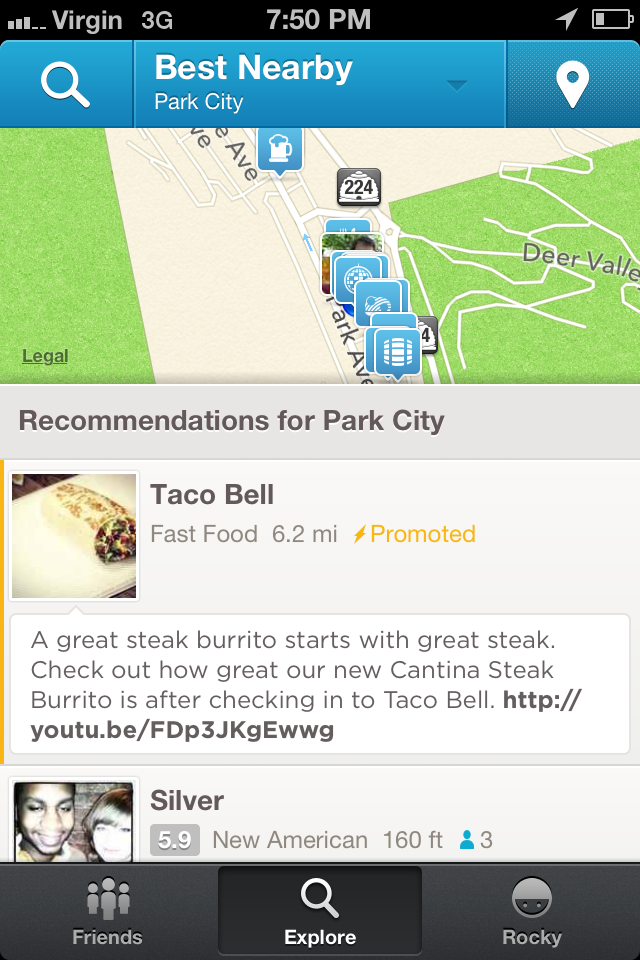

Above: This screenshot explains a lot of Foursquare’s current problems.

“We are not a check-in app or a social app. We’re a shopping app. Everyone who’s using Shopkick is by definition interested in shopping. And that’s inherently monetizable,” Roeding said.

“Monetize” is, of course, the key word here: If Shopkick’s data prove that it consistently brings in customers who make purchases, retailers are going to be more likely to use it.

Foursquare, in contrast, is a lot of things. It’s a location app, but it’s a social app, too. It’s also a game and, most recently, a discovery app. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with being a lot of things to lot of people, Foursquare’s problem is that exactly none of that is what’s making it any money.

To understand the bind that Foursquare constantly finds itself in, consider the screenshot to the right, which shows what happens when a big chain like Taco Bell pays Foursquare to promote its locations. Most people don’t open up the Foursquare app to find a local chain restaurant — they do so because they’re looking for somewhere new and different to go.

The problem is that those “new and different” local spots aren’t at all the companies that are going to pay Foursquare the money it needs to grow. Foursquare, then, is caught between two desires: those of its users and those of its partners.

Shopkick, in contrast, combines the desires of customer and company: When Shopkick users open up the app, they want to shop — and brands and retailers obviously have lots of things to sell them. It’s an ideal merger of inclinations.

The lesson here for Foursquare is simple in theory, but woefully difficult in execution: If Crowley really wants to get the critics off his back, he has to prove that he can consistently lure in partner companies (and $$$) while not alienating all of Foursquare’s users — many of whom who are recently revisiting the app.

As with most things, that’s easier said than done.

Photo: Sean Ludwig/VentureBeat; Foursquare screenshot via Rocky Agrawal