Read more:

Consoles

that won’t die

It’s nearly 30 years old, but the Nintendo Entertainment System is not just a platform for fueling misty-eyed nostalgia. Savvy gamers are also embracing a growing homebrew scene that’s resulting in new physical releases for the aging, but far-from-dead, gray box.

“[Nintendo] would never acknowledge these kind of games exist,” says contemporary NES developer Sivak (he asks to go by this moniker). But they do, and they’re getting a great reception from gamers who still have their NES plugged into an aerial socket.

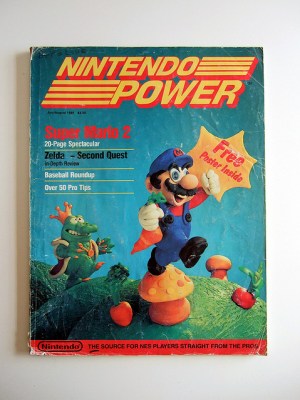

The World’s No. 1 Game System

First released as the Famicon in Japan in 1983, the NES came to North America two years later. It was Nintendo’s first venture away from home soil, and it was a move that set the company up as a market leader in the video game industry.

First released as the Famicon in Japan in 1983, the NES came to North America two years later. It was Nintendo’s first venture away from home soil, and it was a move that set the company up as a market leader in the video game industry.

With thoughts of the great video game crash of 1983 still fresh in its mind, Nintendo took a firm approach to licensing on its home console. Any third-party titles needed Nintendo’s approval before being released on the NES, which, along with first-party exclusives such as The Legend of Zelda, and Super Mario Bros., ensured the system had a killer software lineup. Some of the best-loved gaming properties around today, such as Final Fantasy, Castlevania, and Metroid, all made their debut on the NES.

As IGN said when naming the NES as the greatest console of all time, “Nintendo’s quality first-party efforts as well as the incredibly powerful third-party support resurged and revived the home video game industry. If Nintendo didn’t step up to the plate, the industry as a whole may have turned out entirely different.”

The NES continues to endure to this day. Not just from the lasting impression left by NES debuts such as Final Fantasy, Mega Man, and Castlevania, but from the creative possibilities it continues to offer developers.

The Battle Kid phenomenon

Battle Kid: Fortress of Peril released in 2010. It was the first major platform release for the NES since 1995, and the homebrew title has received a great deal of critical acclaim. “Battle Kid is nothing short of genius,” said retro gaming website Retro Collect. Impressive stuff, particularly for a relative newcomer to NES programming.

“I’ve always wanted to mak e games,” says Battle Kid developer Sivak. “The NES was something I had dreams of, ever since I was young, to make something for. Obviously back then it wasn’t doable. Yet in 2007, when I found out it was, I started researching and doing some things. I made three simple games to get accustomed to programming for the system and finally did the first Battle Kid game after feeling confident in programming.”

e games,” says Battle Kid developer Sivak. “The NES was something I had dreams of, ever since I was young, to make something for. Obviously back then it wasn’t doable. Yet in 2007, when I found out it was, I started researching and doing some things. I made three simple games to get accustomed to programming for the system and finally did the first Battle Kid game after feeling confident in programming.”

Battle Kid: Fortress of Peril was 18 months in the making, but Sivak didn’t wait long before following it up. The sequel to Battle Kid, Battle Kid 2: Mountain of Torment, released in December following a development cycle of nearly two years

Sivak wanted to build on his first major release, taking feedback from the playing community, allowing him to “improve aspects that may have been lacking,” in the first title. This resulted in what he describes as “a much bigger game” featuring 650 rooms, 25 types of enemies, and 13 boss battles.

Fan response to both games has been “mostly positive,” says Sivak, but he acknowledges that the difficulty level is too much for some.

“These are hard games, so I know they aren’t for everyone,” he says. “But people know they’re getting into a hard game when they play it, so those who want a challenge get one and they enjoy it.” With notoriously tricky indie platform game I Wanna Be The Guy (PC) one of the main inspirations behind the Battle Kid series, this focus on pixel-perfect jumps and multiples deaths is hardly surprising.

Sivak himself doesn’t get involved in the production process of the cartridge, which publisher RetroZone handles. “I laid out the label and the manual and the box for Battle Kid 2, but none of the actual circuit board or plastic work is me. RetroZone gets the parts, and as far as the plastic goes, it has a mold that mostly matches the shape of the licensed games.”

Neither Battle Kid title is available to download and play on an NES emulator, so the only option available is to play the physical releases. Demand for these has been “somewhat reasonable,” says Sivak. “Obviously, it’s no modern system, but many collectors are out there and there even people who are discovering the older systems [for the first time]. As long as a game looks interesting and fun to players, there will be buyers.

Neither Battle Kid title is available to download and play on an NES emulator, so the only option available is to play the physical releases. Demand for these has been “somewhat reasonable,” says Sivak. “Obviously, it’s no modern system, but many collectors are out there and there even people who are discovering the older systems [for the first time]. As long as a game looks interesting and fun to players, there will be buyers.

“Most of the games have runs of a few hundred initially, but they get restocked. Demand is highest when something is new, but since there’s still some demand, [there’s] no reason to discontinue.”

Today’s NES gamer

Matt McIntyre is a game collector and NES aficionado based in Nova Scotia, Canada, who regularly blogs about his gaming experiences. He’s been blown away by the quality of the Battle Kid series.

“It holds up amazingly well against the original [NES] library,” says McIntyre, “and that’s even considering the pedestals we place our favorites upon. I think people try to think about these games in terms of what has come before; ‘it’s like Mega Man,’ or ‘it’s like Metroid.’ But these games offer something that may have been missing from the NES library; they fill their own niche.

“When a new title for an old console releases, it’s fine if it pays homage to the classics. But it can’t lose its own identity. These titles bring something to the table that is both exciting and polished.”

For McIntyre, the joy of NES gaming lies partly in recapturing the joys of childhood. “People certainly get attached to what they grew up with,” he says. “Part of what keeps me playing the NES is trying to recapture this nascent sense of discovery and wonder: to discover or rediscover games that pushed the envelope of hardware limitations, or offered a truly unique experience on the platform.

“NES games are close to pure, often spinning out of a concept defined by something as simple as a piece of equipment or particular mechanic. There are lemons, sure. All consoles have them. But sometimes you strike gold and you’re transported back 30 years — sometimes surprised by the elegance, often engrossed in the adventure.”

“NES games are close to pure, often spinning out of a concept defined by something as simple as a piece of equipment or particular mechanic. There are lemons, sure. All consoles have them. But sometimes you strike gold and you’re transported back 30 years — sometimes surprised by the elegance, often engrossed in the adventure.”

Like most gamers, McIntyre understands the visceral thrill of opening a new game for the first time. When it’s a cartridge game for a console like the NES, that thrill increases.

“There’s something special about getting a brand-new cartridge that just brings you back,” he says. “I would still love these games were they released purely in digital format, but there’s a certain level of excitement that comes with a physical cart. Taking into account the NES enthusiast’s mentality, there’s the thrill of owning a new cart for one of your favorite consoles. And in terms of the NES library, it canonizes the release. It puts the game up to all of the scrutiny and accolades and consideration that every other title in the library receives. It doesn’t necessarily legitimize a game — the quality of the title regardless of downloadable or cartridge does that. But it makes us think of it clearly as an NES game, because it has arrived.”