Gavin Moore, creative director of the upcoming Puppeteer for the PlayStation 3, says he wants to be able to play his platform/action game with his kid. A game that’s about a maniacal tyrant who beheads a young boy. A game that takes place in dark, frightening worlds. A game that has tons of spider webs.

Good thing Moore has a 9-year-old — any younger might give us pause.

He calls Puppeteer, “a dark fairy tale that we’ve written for children and adults,” but it’s so much more interesting than that. The unusual presentation has you controlling protagonist Kutaro (the headless boy) in sets that evolve and swap as different scenes play out. The world advances around you more than you advance within a world. Picture a theatrical production right in front of you complete with a narrator and a “live” audience that reacts appropriately. (“That came about because I would come home late at night, play my game, and no one would be around to cheer me on,” says Moore). Except that you can manipulate the on-stage antics.

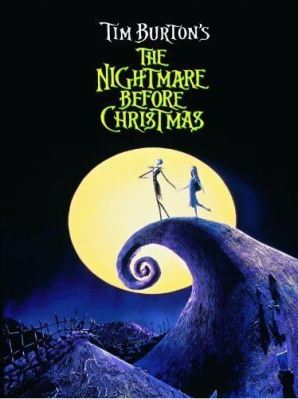

And yes, Puppeteer is scary. But it’s scary in a most lighthearted and oftentimes humorous manner. (See page two for more screenshots plus a trailer.) We’d almost call it Tim Burton-esque if Moore didn’t beat us to it.

During a recent press demo, he cited the quirky movie director as one of his biggest inspirations on this particular game, and that got us wondering: What are all the twisted — and dark — sources that influenced Moore and his vision for Puppeteer? We asked, and he offered his thoughts on …

… movie director Tim Burton (Beetlejuice, The Nightmare Before Christmas)

Gavin Moore: One of the funny things about Tim Burton is that he’s originally an animator, which is what I was before I became a creative director. His moving into being a director is a very substantial vision for me as well — moving from being an animator to doing my own thing.

Gavin Moore: One of the funny things about Tim Burton is that he’s originally an animator, which is what I was before I became a creative director. His moving into being a director is a very substantial vision for me as well — moving from being an animator to doing my own thing.

But the wonderful thing about him is he has this great eye for detail. There are all these small touches in his movies. If you look at it once — if you watch the movie once, you miss tons. Then you look at it again and say, “That’s kind of cool. I didn’t realize he’d even bothered to go that far and put that in.”

Puppeteer is like a sensory overload because everything’s moving around you at the same time. Characters are speaking all the time. The audience is reacting all the time. There’s a lot of stuff that you might not pick up or see. People are saying, “I want to see everything, and there’s too much going on!” Well, play it again. Enjoy it again. Watch it and pick up all those little things you didn’t see the first time around. That’s one influence [Burton had] on the creation side of it.

For instance, we break the fourth wall a lot. As the player progresses, the argument between the owner of the theater, who’s narrating, and some of the cast members — and the way they react to the audience — starts to happen. But then, in the background where other characters are acting, some of the actors are having a go at each other. It’s just something you don’t pick up on. But once you go through it and start to see those relationships happening in the story — or outside of the story but inside the theater — you start to pick up on those.

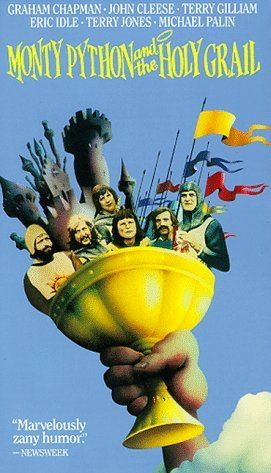

… comedy troupe Monty Python (Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Life of Brian)

Moore: I grew up on Monty Python, being English. That’s the basis of all great English humor. It’s just the way they could do something completely insane and make it funny.

Moore: I grew up on Monty Python, being English. That’s the basis of all great English humor. It’s just the way they could do something completely insane and make it funny.

That was a great influence for us on Puppeteer. We knew we were going to make it crazy and wacky, and we wanted to keep people playing. They’d want to keep seeing what this bizarre game was showing them. The situations that our hero gets himself into are more and more insane as you progress through the game. So that was a big influence.

How can you possibly do a sketch like the Ministry of Silly Walks? It’s such a British thing, right? Here’s a ministry that exists in Parliament where all they do is give money out to people who have silly walks. But Puppeteer is full of those little individual situations of weirdness. You’re playing the game in this main part of the story, but there are so many characters coming at you from all different angles that are doing these bizarre things. You’re kind of like, “What’s that about?” Then, “Oh, OK, I get it” — it links to something later on in the game.

One of my favorite characters that is completely, utterly pointless in the whole game — doesn’t need to be there at all — is the vampire. He’s been told that there’s no sun on the dark side of the moon, so he moves from Earth to the dark side of the moon. But he can’t find any female virgins to suck their blood.

You wake him up out of this coffin, and he sits up there, and he’s all depressed. Then he starts going on with his little monologue, and he starts saying, “Oh, they told me to go to the dark side of the moon and blah blah blah, but I’m a vampire, and there aren’t any virgins here, wah wah wah. I remember the good old days when I could go down to the local village and suck the blood of loads of women, and they were afraid of me, and they were afraid of the dark. Then this Edison came along! He made electricity!”

He just goes on with his own monologue about the disappointment of his life, which is full of these little points about human nature and stuff. We’re not afraid of the dark anymore. We used to be, but now we’re not. Most kids have seen more violence in video games — he goes on about that. “Why should they be afraid of me?” Pixel shaders and all this sort of stuff — he goes on about that. There are these little hints for gamers and game creators in there.