Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

This is a guest post by Dr. Paul Langevin

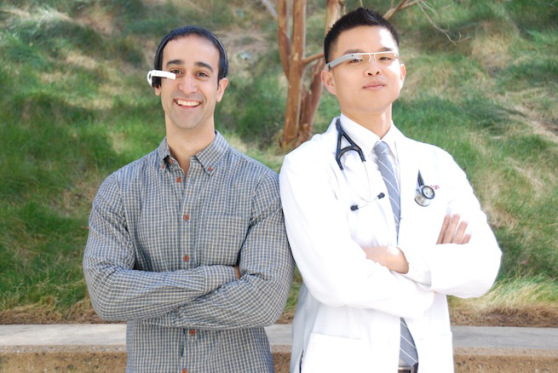

Google Glass has the potential to greatly enhance medical practices in a number of ways, VentureBeat recently reported. Among these is the ability to retrieve, see, and disseminate information rapidly and efficiently.

However, Google Glass for health care will remain a concept — rather than a practice — until developers gain a better understanding of the medical environment. There are constraints that non-clinicians seldom realize even exist, and the success of any product in the industry is ultimately determined by its functionality in that environment, regardless of how ingenious an innovation may be.

AI Scaling Hits Its Limits

Power caps, rising token costs, and inference delays are reshaping enterprise AI. Join our exclusive salon to discover how top teams are:

- Turning energy into a strategic advantage

- Architecting efficient inference for real throughput gains

- Unlocking competitive ROI with sustainable AI systems

Secure your spot to stay ahead: https://bit.ly/4mwGngO

As a physician, here’s my take on how Google Glass developers can navigate the operating room, and other clinical settings.

The true meaning of “hands free”

This lack of insight into the clinical environment is demonstrated by the “hands-free” technology of Google Glass. A hands-free system in the clinical sense would need to be very literally hands free. I cannot overstate how problematic it would be for a doctor to wave their hands about in a sterile environment. Touching or even nearly touching a sensor to interact with the system would sharply curtail the device’s utility in any procedural environment.

Touching anything that is not sterile, whether it is the Glass or something in proximity to it, would require the doctor to change whatever touched the device such as a gown sleeve, glove or instrument.

Furthermore, a pop-up menu can be and will be very distracting. Non-clinicians do not realize that it is not unusual for some physicians to receive 20 or 40 pages in an hour on our beepers.

These auditory distractions are intrusive enough and at that kind of a rate, they become more than a nuisance. Most physicians dislike beepers because they require us to stop what we are doing, look at the number displayed on the beeper, and call to see what the issue is.

For this reason, texting by cell phone has largely replaced audible pages. The pop-up display of Google Glass is a visual distraction rather than an audio one — it is more difficult to ignore. But it would be useful if the system could filter what gets through to the physician at any time, blocking out all but the truly critical information.

Dealing with sensitive patient data

Maximizing utility of Google Glass will require access to Patient Specific Information (PSI), such as the electronic medical record (EMR). This alone would be reason to strictly limit — if not prohibit — the use of Google Glass in the clinical environment unless it was user selective, or at the very least, password protected. If the glasses were tailored to physicians so that no one else could use them, this would ally concerns about unauthorized access to PSI and reduce theft.

Another suggestions would be to build apps for Glass that can recognize a patient. In that case, an authorized user, even a clinician, would not be able to retrieve information they should not have. To cite a specific case, a physician and a victim of assault were taken to a hospital. Hospital administrators could track exactly who accessed the patient’s record. Nearly 50 employees at that hospital were disciplined or discharged — it became apparent that they had accessed the medical record but were not involved in the patient’s care.

Google Glass has the potential to not only restrict general access to patient data, but also select what information can be viewed by that specific user.

Another good idea that never fulfills its potential?

The device must operate with sufficient speed to allow near instantaneous retrieval of information that typically involves huge files such as display of an x-ray or CT scan. Achieving this may be quite problematic in a wireless device.

Hospitals might need broader bandwidth and/or faster transmission times to accommodate the device.

The biggest problem with Google Glass is cost. If there isn’t a real advantage to the physician and to patient care, the expense of the device and modification of other systems that support it can’t be justified.

Google Glass has potential — but developers will need to work with physicians to build apps that can function in the clinical environment with all of its medical, biological, administrative and regulatory constraints. Otherwise, Google Glass will be just another good idea that never fulfilled its potential.

Paul B. Langevin MD. Cardio Thoracic Anesthesia, Critical Care MD at Hahnemann University Hospital and Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Biomedical Engineering, Drexel University College of Medicine. Global speaker, author, multiple patent-holder, and a medical consultant.

Paul B. Langevin MD. Cardio Thoracic Anesthesia, Critical Care MD at Hahnemann University Hospital and Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Biomedical Engineering, Drexel University College of Medicine. Global speaker, author, multiple patent-holder, and a medical consultant.

Top image via Augmedix