Updated 9/16: Amplify’s software isn’t limited to educational games: It also includes other forms of educational software. I’ve updated this post to reflect that.

Educational reality is taking a strange science-fiction turn.

Amplify, a 650-person Brooklyn startup headed by the former chancellor of the New York city school system and funded by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., envisions a future where childhood education is centered on tablets that teach children through fun games and interactive lessons.

We covered the launch of Amplify a year ago. In March, the company launched its tablet, and it recently scored its first paying customer, a school district in North Carolina, which will be deploying 21,215 Amplify tablets starting this year.

Amplify is also the focus of an extensive profile in today’s New York Times Magazine, which takes a look at the pros and cons of tablet education as delivered by Amplify.

There’s a lot to extract in the Times piece, but here are some of the highlights.

The tablet

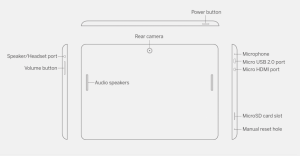

The Amplify tablet is a 10-inch device running a modified version of Android 4.2 “Jelly Bean.” The Amplify site describes it as “similar to an ASUS MeMO Pad ME301T,” which suggests that Asus is the manufacturer of the hardware. It’s running an Nvidia Tegra 3 quad-core processor with a 12-core GPU, a 5 megapixel camera, a microSD slot, micro HDMI port, and micro USB port. The amount of storage it contains is unspecified.

It’s got the usual complement of Android software, including Chrome, Mail, Calendar, Google+ (including Hangouts) and so forth; the tablet also comes with Skype and something called SuperNote preinstalled.

The cost is $199 per year for the Wi-Fi-only model, or $325 per year for the version that includes 4G data connectivity, both with a 3-year contract. That could run to some real money for a school that has hundreds of students, of course: For the North Carolina school district, its 21,215 tablets could cost it $4.2 million per year (though it has probably negotiated a substantial volume discount).

The goal of the Amplify tablet is to teach children via engaging interactive software, including games. As they play, the software leads them through a curriculum set by the teacher, helping them learn at their own pace. Their usage also generates data that the teacher and school district can use to assess progress, adjust the curriculum, and focus better on students’ needs.

“Think of school as a not very good game,” says Amplify’s Justin Leites, a vice president in charge of games, in the Times story. “You pretty much know at the beginning which kids are going to come out on top at the end, and they do.”

Amplify’s games, by contrast, are meant to be more challenging, more interesting, and more effective. They are “meant to feel like free play, not more schooling,” the Times writes.

The data

The Times writer notes a whiteboard behind Leites’s desk at Amplify’s hip Brooklyn headquarters that says “DATA: That’s what I want!”

And it does appear that a big part of Amplify’s business is figuring out how to collect, manage, and use the data generated by all those tablet-using, educational game-playing students.

It’s potentially a huge asset to education, although using it will be a challenge, particularly for school districts on the less tech-savvy end of the spectrum.

“They used to have too little data from students,” Supovitz says, “and now they’re going to get too much, and they need to be ready,” the Times quotes University of Pennsylvania education education policy expert Jonathan Supovitz as saying.

The controversy

Is all that data collection a good thing? Not everyone agrees. The Times:

“When you’re talking about Rupert Murdoch and his empire,” says Josh Golin, the associate director at the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, “there are a number of ways that data could be valuable to his companies beyond instruction.” Klein, who has grown used to addressing privacy concerns, says flatly, “The data belongs to the district.”

Beyond data collection, there are other concerns. Is spending that much time staring at a screen really a good thing? Apparently, there’s not much conclusive data either way, though research is underway to try and get a better fix on this. The Times quotes experts such as MIT’s Sherry Turkle who express skepticism about the virtues of spending so much time glued to digital media — students are losing the ability to have normal face to face conversations, for instance, she claims.

The science fiction

Reading the Times story, I kept thinking about Neal Stephenson’s “Diamond Age,” a science fiction novel published in 1995. In that novel, the plot centers on a digital “book” that is designed to educate children by guiding them, through interactive games and self-guided discovery, all the way from pre-literacy to advanced research. Things take a turn when the e-book gets co-opted by activists who duplicate it and put it into the hands of hundreds of millions of Chinese girls, who grow up to become an empowered, incredibly intelligent army of world-changers.

Now imagine that the digital book is an Android tablet, and that it is being created by a wholly-owned subsidiary of News Corp., Rupert Murdoch’s globe-spanning media empire.

It’s not the first time that someone has attempted to put Stephenson’s vision into reality. One Laptop per Child has long aimed at a similar goal, by putting durable, usable laptops and tablets into the hands of underprivileged children in underdeveloped countries around the world. But OLPC has not met with widespread success, apart from a few isolated wins.

Can a media conglomerate succeed by selling tablets for $200 to $325 per year, where a group of idealistic MIT-led world changers have not?

Time will tell.