Price spikes at busy times will continue indefinitely on Uber’s alternative car service.

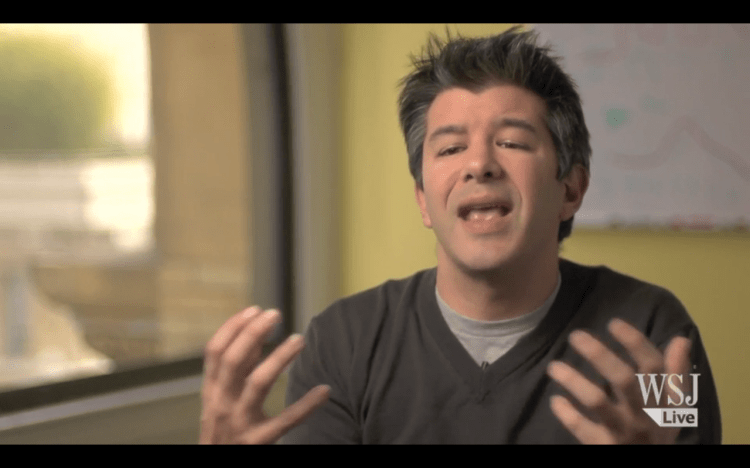

Chief executive Travis Kalanick talked up the importance of the feature in an interview today with the Wall Street Journal. It’s a bold position, coming as it does just a few days after an Uber driver got into a fatal accident while surge pricing was in effect, even if the driver wasn’t providing Uber services at the time.

This matters because the practice is not just unpopular with riders — it could encourage drivers to drive more recklessly in order to pick up more high-priced fares.

“The price must go up for these rides to happen,” Kalanick said in a video interview with the Journal. “If surge pricing doesn’t happen, there is no availability. You can’t get a ride.”

Kalanick defended the practice of surge pricing, arguing that it’s comparable to paying more at certain times for a hotel room or an airplane flight. “You’re OK with that, and you understand it,” Kalanick said in a transcription of the interview. “But in ground transportation, there’s been fixed pricing for 100 years. Because of that, there’s an education process.”

The interview did not apparently touch on the death of 6-year-old Sofia Liu after a car accident in San Francisco on New Year’s Eve, which involved Uber driver Syed Muzzafar.

But now that Kalanick is talking about publicly about surge pricing, it’s worth asking if raising prices during peak hours might have played a role in the fatal accident.

Uber’s surge pricing was in effect on New Year’s Eve and early into New Year’s Day.

Now, let’s be clear: Uber has stated clearly that Muzzafar was an Uber driver but that he “was not providing services on the Uber system during the time of the accident.” (Uber subsequently terminated the relationship with him.) But Uber has not stated whether Muzzafar provided Uber services at other times that evening, and the company did not respond to repeated requests for clarification.

A quote for an Uber trip that would have started seven blocks from the site of the accident and ended minutes before 2 a.m. at San Francisco International Airport came out to $227. Rakesh Agrawal, a VentureBeat guest post contributor and principal analyst at reDesign mobile, tweeted out a screenshot of the quote for the ride early on January 1. By contrast, a typical cab ride from downtown San Francisco to SFO costs about $50 to $60, according to TaxiFareFinder.

Uber gave people a heads up for the high prices on New Year’s Eve in a Dec. 30 blog post. A chart in the post suggested that a moderate level of surge pricing could be in effect between 8 p.m. and 10 p.m. on New Year’s Eve. That would have been the case at the time of the accident.

The company estimated a higher level of surge pricing for the time period when Agrawal checked the price of a trip to SFO (after midnight).

But it’s not like Uber is the only company that raises prices at certain times. Uber competitors Lyft and Sidecar have implemented systems similar to Uber’s surge pricing.

Lyft has an on-peak pricing feature called Prime Time Tips. Lyft drivers take home the tip, not Lyft itself.

Fares ran as high as 100 percent more than usual early on New Year’s Day, a Lyft spokeswoman said in an interview with VentureBeat, although in the preceding days, rates hovered at around 25 percent higher than usual, she said. The company instituted a cap, preventing rates from shooting higher than 200 percent above what’s normal, the spokeswoman said.

In December 2012, Sidecar revealed plans to use surge pricing on New Year’s Eve of that year.

This time around, Sidecar raised prices as much as three times higher than its usual rates, between 8 p.m. on New Year’s Eve and 4 a.m. on New Year’s Day, a spokeswoman wrote in an email to VentureBeat. The higher prices “incentivize drivers to get out on the road during peak hours when people needed them the most,” she wrote.

San Francisco taxis, by contrast, do not alter their prices based on demand. The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency mandates that each taxi charges $3.50 for the first one-fifth of a mile it drive after a passenger flags it down. After that, every one-fifth of a mile bumps up the price another 55 cents, and every minute of waiting because of traffic increases the price 55 cents. Riders must pay an extra $2 for a trip to SFO. Drivers charge 150 percent of the rate based on a meter for trips more than 15 miles from the airport, except when drivers go through the city from the airport to Marin County or the East Bay.

Robert Werth, the president of the Taxicab, Limousine & Paratransit Association, a nonprofit trade group representing transportation operators, came out against the practice of surge pricing in a statement a spokesman provided to VentureBeat.

“Transportation app operators should not be allowed to continue to implement surge pricing at will, as this introduces a new driver safety concern for passengers,” Werth said in the statement. “Drivers may speed and ‘stack calls’ to take maximum advantage of the price-gouging revenue opportunity. People who need a ride in a snow or rain storm, in the middle of the night, in a more remote location, or a pickup in a dangerous neighborhood will be faced with either paying price-gouge rates, or getting no ride at all.”