Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

In a former life, Stocksy CEO Bruce Livingston’s job was replaced by software. Today the former iStockphoto founder and CEO and former Getty Images VP could be replaced by photographers — the very people he’s enticing onto his new stock photography platform.

Call it democratic capitalism … and that’s just one of Stocksy’s unique points of craziness.

“The inherent problem with the stock photography industry is that companies care about companies … and they care about keeping their margins high — 70 percent plus,” Livingstone told me recently. “I thought: Why don’t we try and do things completely backwards? Let’s invert that revenue pyramid so that photographers are on the top.”

Livingstone should know. He started iStockPhoto and sold it to Getty Images for $50 million.

iStockPhoto was born just after his first pay-for-university job went up in smoke. He was a clerk at Image Club Graphics, a clip-art vendor, and his role was to transfer credit card numbers from one company system to another in the dark ages of technology. Once software solved that problem, he was out of work.

But the CEO liked him and asked Livingstone to invent a new job and pitch the company on it. He came up with a system where clients could dial up on a BBS or the nascent Internet, buy a photo online, pay via credit card, and not have to talk to anyone at all.

But the CEO liked him and asked Livingstone to invent a new job and pitch the company on it. He came up with a system where clients could dial up on a BBS or the nascent Internet, buy a photo online, pay via credit card, and not have to talk to anyone at all.

“This is the future of your business,” Livingstone told the leadership of the company. “They all thought I was smoking crack.”

ImagePub’s failure of vision led to Livingstone actually smoking crack. He quit university, raised about $50,000 as a 20-something kid, and started both a web-hosting company and an advertising firm to pay the bills for what he actually wanted to do: build iStockphoto. It began life as a photo-swapping site, then evolved to sell credits that could be redeemed for photos for $0.25 each — thereby inventing the notion of the credit pack and implementing, essentially, a virtual currency for micro-transactions.

Necessity was, of course, the mother of invention, as $0.25 was far too little to charge to credit cards.

In 2006, after iStockphoto hit $12 million in revenue, Getty offered $50 million for the site, and Livingstone, thinking “how much money does one person need,” accepted. He moved to L.A., took on a role as a senior VP with Getty, and stayed there for three years.

Then he tried to retire.

“A lot of photographers kept visiting us, and they kept saying the same thing: Competition is getting too fierce, there’s a whole ocean of images to compete with, Getty and other stock photography sites were changing their royalty structures … and they weren’t getting the same revenue anymore,” Livingstone says. “A lot of people gave up … it was really hard for me.”

Livingstone quit the job and moved back to his native Victoria, B.C.

Livingstone quit the job and moved back to his native Victoria, B.C.

It’s the place on Vancouver Island that all tourists to Western Canada visit for a taste of English life, complete with double-decker buses, red phone booths, quaint shops, and old-ish architecture … plus some whale-watching, fishing, and hiking.

But he didn’t quit the mission: help stock photographers.

Stock photography is a hard gig in the modern world. No longer is it prohibitively expensive to buy significantly good equipment. And, where once shooting a roll of film meant paying out $10-20 in development fees, now there’s no incentive to economize. With digital photography, everyone became a photographer. Or at least, so it seemed to the pros, who saw amateurs inundate the stock photography portals with cheap images.

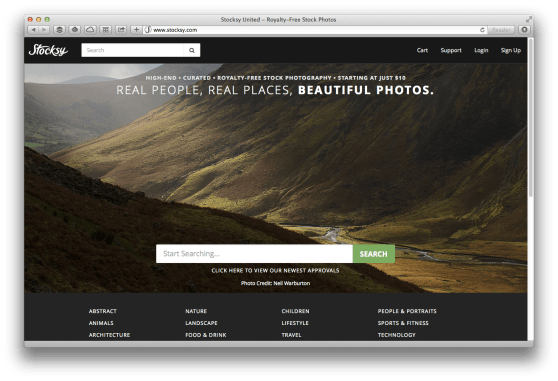

So Livingstone decided to upend the model, and he started Stocksy — a new kind of stock photography company.

“Let’s share equity, let’s pay as much as possible, and let’s give the control to the community,” he told me. “I’m the CEO and president right now, but if there is an election and the majority of people decide I’m not fit for the job anymore, they can elect someone else. It’s a really true democratic system.”

The key to Stocksy is that the number of photographers is kept low.

New members must be invited by existing members. And then, only photographers who pass an extensive screening process — including portfolio review and Google Hangout interviews — can join. Once they do join, they become shareholders in the company. In addition, Stocksy can never add more than 500 photographers in a year, by rule, differentiating it from competitors with 100,000 photographers.

New members must be invited by existing members. And then, only photographers who pass an extensive screening process — including portfolio review and Google Hangout interviews — can join. Once they do join, they become shareholders in the company. In addition, Stocksy can never add more than 500 photographers in a year, by rule, differentiating it from competitors with 100,000 photographers.

The result is high quality uniformly across the site, and less competition. The first is good for customers, including Apple, and the second is good for photographers.

“We don’t try to flood our collection with thousands and thousands of photographs,” Livingstone told me. “We have only 60,000 images right now … but every single image is really special. There’s no filler, none of the types of stock photography that has become a parody.”

It seems to be working.

Photographers who join have started dropping exclusive deals with Corbis and Getty. Those who have “risked it all,” Livingstone says, are “making a living.” One, Sean Locke, is pulling in close to six figures annually. Stocksy is growing at 20-25 percent every single month, and January was the community’s strongest month ever, with 41 percent growth and $85,000 paid out in royalties.

As far as royalties are concerned, Livingstone said they are as high as possible.

“90 percent of profits are shared with photographers,” he says. “We’re not a nonprofit — we try to make as much money as possible to pay as much as we can to photographers, but the company itself keeps no cash.”

Time on site is almost 12 minutes, and cart conversion is over 50 percent, Livingstone told me — both of which are significantly higher than competitors.

“It is really photographer and shareholder controlled,” he says. “That may be daring and silly, but so far, it’s really working. We’ve been up for 10 months, and we’re in the black.”

“That’s also pretty unheard of for any startup.”