Craig Robinson is the cofounder of Absolute Hero Games.

Last year we had the opportunity to create a series of five mahjong link games (a variation on the standard) in HTML5 for Spil Games. The first game we built was Dream Pet Link. Given that we were tasked with building four additional games with the same mechanic but different themes, we knew we’d be able to reuse much of the same code. We could just write the first game and then swap in new art and sound assets for the subsequent titles!

Oh, only if things were so easy.

A few issues made things more complicated:

- Desire to reuse some code in other games that didn’t have the same mechanic

- Uncertainty about code changes necessary to accommodate differences in the art and audio

- Features and performance improvements we knew we would discover later in the cycle

These considerations forced us to take a different design approach than we had initially anticipated. This article discusses the process we went through to build these games while creating code libraries for use in these and our other HTML5 games. As you will see, the process was fluid and organic. We also describe why JavaScript proved to be an ideal language to support our work.

Start your engines

Start your engines

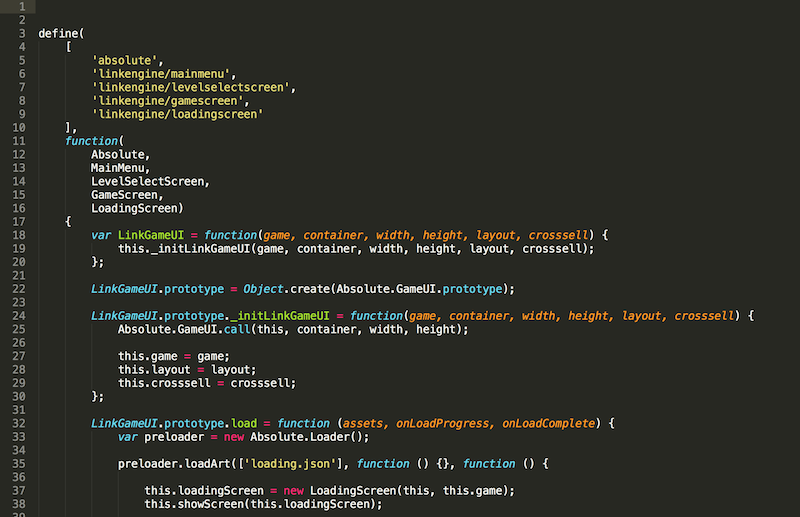

We decided that functionality would be organized into three distinct buckets: code and configuration files specific to a given game; code that could be shared by all the games with this mechanic (we called this LinkEngine); and code that could be used by any game (we called this the Absolute library).

It wasn’t always immediately clear which bucket we should place a particular functionality into. Sometimes we would build a feature, and only after working with it for a while, realize that it could be made more generally useful. We would then promote it to the next level of abstraction and move it to a different bucket.

We didn’t start to split out game specific code from LinkEngine until it was time to build the second game. By that time we felt like we had a pretty good handle on what needed to be in the Absolute library, but splitting the game specific code from LinkEngine was a process that, as we describe below, required some additional effort that we believe provided a better result than if we had tried to make this separation in advance.

What do you mean you want to use a larger font?

One thing we didn’t address in the first game was how changes to the graphic assets would affect the layout of onscreen items. Some of the graphics were positioned relatively, but others had fixed/hardcoded locations. This scheme broke down when we built the second game. The theme of each game was different, and our artists chose a different font (with different metrics) for text in each game. Other asset sizes changed as well, such as the game logo, buttons, dialog box frames, progress bars, etc.

In order to accommodate these different sizes we changed some asset positioning from fixed to relative. In situations in which this wasn’t appropriate, we created a game specific JSON layout file that provided coordinates for various assets. We wrapped this functionality in a Layout class that hides the complexities from the rest of the code.

One might argue that we should have foreseen the need to support more flexible layouts up-front and we could have saved ourselves some effort by planning for differently sized assets in advance. In fact, we did anticipate this issue, but we chose not to address it up-front. The game design was very fluid, we didn’t know which features and items would stay in the game and which would go, and we knew we could easily re-factor this later.

By putting off the work to build a more flexible layout mechanism we ended up with a more elegant solution, because we were able to collect more information about the type of features and functionality required across a number of scenarios.

Sounds about right

Each game had unique sound effects with different lengths, but we were able to use these without code changes. We stuck to the same structure; the same actions caused sound effects and we had a couple of different music tracks for different parts of the game. A JSON configuration file enabled us to easily remap existing actions to new audio assets.

We made significant improvements to our audio capabilities in between the first and second games, so we wanted to work these in, too. We added the capability to work with audio sprites, which allowed us to place sound effects with lower latency on devices without Web Audio API support. We used a Grunt (JavaScript automation tool) task to automate the creation of audio sprite files from our existing audio assets.

We now have an audio library that provides scalable support across platforms by taking advantage of high-end capabilities where available, and falling back to less rich, but still acceptable functionality, where not.