Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

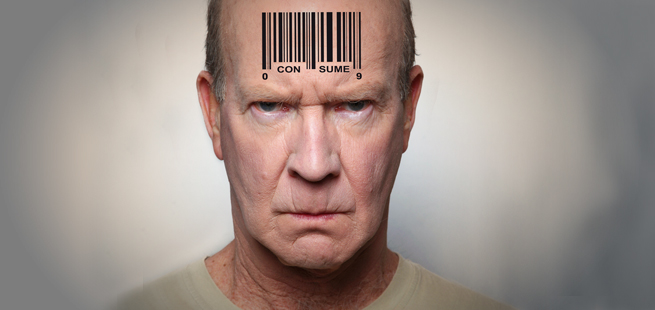

Companies today collect a lot of data about their users. People often divulge highly private information, and companies reassure them that what’s done with the data is limited by strict privacy policies that customers agree to when they sign up.

However, these privacy policies offer no real protection to users. Companies can and do change their policies on a whim, without user consent.

What’s the solution? Legislators need to step up to ensure that personal data is protected.

We need to shift from an opt-out approach that puts the burden on users to protect their private information to a more orderly, opt-in approach that puts user privacy first.

AI Scaling Hits Its Limits

Power caps, rising token costs, and inference delays are reshaping enterprise AI. Join our exclusive salon to discover how top teams are:

- Turning energy into a strategic advantage

- Architecting efficient inference for real throughput gains

- Unlocking competitive ROI with sustainable AI systems

Secure your spot to stay ahead: https://bit.ly/4mwGngO

A simple first step is for Congress (or the California Legislature) to pass a bill that requires companies to get users’ consent before they change their privacy policy.

The new law could simply state that if an organization wants to change the way it uses customer data; it needs to get permission from the customer first. If an individual customer doesn’t agree with the new terms, the organization would have to maintain its original privacy policy towards that customer or surrender all the personal information it has collected on the customer and cancel the account — end of story.

The (lack of) privacy laws today

Companies often tell users about privacy policy changes in a late-night email that goes unnoticed and requires no action from the customer. The fact that a privacy policy can be changed at a moment’s notice, without the user’s consent, has led to an “anything goes” attitude towards people’s personal information.

Facebook’s recent plan to acquire the messaging service WhatsApp is the latest in a string of examples of this attitude.

People who signed up for WhatsApp agreed to an unusually strong privacy policy, which promised not to collect user names, email addresses, or phone numbers. WhatsApp stated it would not store any messages on its servers and pledged not to share personal information with third-party companies or advertisers. Experts agree that WhatsApp’s strict privacy policy, along with its intense focus on simplicity, made the messaging service especially popular with customers, paving the way for it to become the fastest company in history to reach 450 million users.

But now that WhatsApp has agreed to sell itself to Facebook, those promises could go out the window. Facebook can use any of the data that WhatsApp has already collected for any purpose simply by changing a few words in the existing privacy policy.

Furthermore, Facebook could start collecting other information about WhatsApp users and selling it to advertisers or other interested companies.

For people who signed up for WhatsApp under the promise that their data would be closely guarded, there’s nothing they can do to regain control of their information. They can stop using the service, but even then they can’t take back the data they’ve already shared.

The Facebook/WhatsApp deal isn’t the first time these concerns have cropped up. Google’s recent acquisition of the home automation company Nest Labs allowed the Internet giant to gain immediate access to millions of Nest users’ personal information.

In 2012, Facebook acquired photo-sharing app Instagram and its enormous user base — and then quickly changed its privacy policy to allow it to sell users’ photos to advertisers without notice or compensation. Major public outcry eventually forced Facebook to reverse this policy change, but Facebook kept some of the privacy policy changes, including the right to access any of the user data Instagram collects.

A simple solution

Because many companies have shown their reluctance to stick with their own privacy policies, it’s time for legislators to get involved.

Congress should craft a law that requires companies to get users’ permission every time they want to change the way they use customer data. Instead of just requiring companies to post privacy policies, as California now does, the law should require companies to abide by those policies until they get consent from the customer to make a change.

Many companies will immediately protest that such a law would make their operations too complex and difficult to manage. Companies that want to keep old users but instate new privacy policies would have to keep track of which customers fall under which guidelines.

This would create different sets of customer bases for each privacy policy update rather than a single mass of customers under the same rules. Companies will decry that this prohibits innovation, interferes with business practices, and so forth.

It would indeed be difficult for organizations to manage such a process, especially if they’re changing their privacy policies on a monthly basis, but this is precisely the point of such a law. New rules would encourage companies to think more seriously about how they use customer data from the outset. Instead of changing the policy every time the company has a new idea about how to use customer data, the company would have to think in advance about how it plans to monetize sensitive information and stand by that promise.

Companies would also have to consider whether their plans for the customer data are something users will accept. In the long run, this should lead to more stable privacy policies, and customers could put real faith in the promises that companies make about using their personal information.

Ethan Oberman is CEO of SpiderOak.