Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

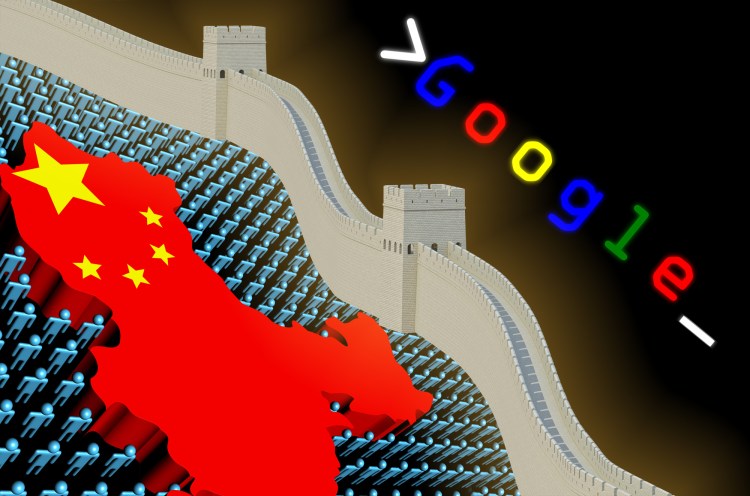

Apparently, China’s “Great Firewall” now stands between the country’s citizens and Google services.

As the 25th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre approaches, China has blocked access to all Google services, according to censorship watchdog GreatFire.org. Google search, Gmail, Google translate, and “almost all other [encrypted or unencrypted Google] products” have been largely inaccessible to Chinese citizens since Friday, GreatFire contributor Percy Alpha (a pseudonym) said in a blog post Monday.

“It is not clear [whether] the block is a temporary measure around the anniversary or a permanent block. But because the block has lasted for four days, it’s more likely that Google will be severely disrupted and barely usable [in China] from now on,” Alpha speculated.

Google told Reuters “there’s nothing wrong on our end” that would disrupt the company’s Chinese services, and offered VentureBeat a similar statement in response to our queries: “We’ve checked extensively and there are no technical problems on our side.”

AI Scaling Hits Its Limits

Power caps, rising token costs, and inference delays are reshaping enterprise AI. Join our exclusive salon to discover how top teams are:

- Turning energy into a strategic advantage

- Architecting efficient inference for real throughput gains

- Unlocking competitive ROI with sustainable AI systems

Secure your spot to stay ahead: https://bit.ly/4mwGngO

Chinese officials have not confirmed the block, but the country has a long history of broad censorship, offline and online. Google’s transparency report, meanwhile, shows significantly lower levels of traffic from China beginning Friday.

In early 2010, Google announced it was no longer willing to censor searches in China and moved its Chinese operations to Hong Kong. China condemned the decision and blocked many of Google’s services, including video streaming site YouTube. China also currently blocks Facebook, Twitter, and other popular social networking sites.

We caught up with GreatFire.org cofounder Charlie Smith to learn more about how China’s Google block affects the people of China, Google, and the country’s broader censorship efforts.

Eric Blattberg: What are the ramifications of this widespread block?

Charlie Smith: First of all, it makes all users of Google services aware of censorship issues in China. To be honest, the Chinese censorship authorities have spent quite a lot of energy disrupting Google in the past. And many users of Google services, in particular search and Gmail, have likely migrated to other services to avoid the hassle in exchange for losing their privacy — although post-Snowden, I guess that Internet users in China have to choose between their own government snooping on their communications or a foreign government doing the same. So in the first place, I think although Google’s market share is tiny compared to its domestic competitors, we’re still talking about tens of millions of Chinese being affected by this total block.

It also generates considerable media attention about censorship in China. You might not draw a lot of attention when you shut down a small June 4th memorial website, but you certainly draw more attention when you shut down one of the biggest Internet companies in the world. To be honest, I think the authorities are really making a mistake on that front. Why draw the world’s attention to increasingly burdensome censorship restrictions in China? I think most people outside of China understand that there are strict Internet controls in China, but it certainly does not cast China in a positive light.

Furthermore, the Chinese authorities have really miscalculated the preponderance of online media outlets in China in both Chinese and non-Chinese languages. Many of these media outlets will report on this story, which only serves to make Chinese netizens more curious about what all the fuss is about.

Eric Blattberg: How are the people of China reacting to the block?

Charlie Smith: We can see some of the comments that the authorities have deleted on Sina Weibo on our sister site, FreeWeibo.com. We’ve been monitoring censorship since 2011 and I think we have seen a real shift in the reactions of Chinese to censorship. Earlier this decade comments were largely abusive and frankly vulgar — a lot of “f*ck the great firewall and f*ck the motherf*ckers who constructed it” type stuff.

But now I sense most of the comments express some pity towards the authorities. More like, “Are these idiots still at this game?” and “Do they take us for such morons?” (Pop this link into Google Translate if you don’t speak Chinese and you can read for yourself: https://freeweibo.com/weibo/%E8%B0%B7%E6%AD%8C?censored)

I think that Chinese are having a hard time balancing this kind of censorship inside of their own heads, too. Chinese certainly enjoy many economic freedoms and the freedom to travel. So many are wondering, why can’t we have freedom of access to information?

Eric Blattberg: What’s Google’s stance here?

Charlie Smith: Google made a statement to Reuters earlier today saying something like “everything is fine on our end,” which I assume means they are considering their response. First of all, the authorities have not 100% blocked search and Gmail, they have just severely disrupted these services so Google can legitimately say “seems normal on our side” while the Chinese can legitimately say “we haven’t completely blocked Google.”

From our perspective, these reactions are part of a slow chess match. Google is the dominant player here — it could be checkmate for them in a few moves. But for whatever reasons — economic, political, social — they want to let this game unfold slowly. We’re getting impatient watching this stupid match because like everyone else we know Google can kick censor ass. So we introduced a timer for their moves today [prompting Google to] unblock Google search in China and make sure it is accessible to everyone without the use of circumvention tools. Now that the timer is running, both parties are going to have to make their moves faster now, and when it has all played out, we are confident that we’ll see the end of censorship in China as a result.