Adesto Technologies is unveiling today its super-low-power memory chips that can be used in a new class of Internet of things sensors, wearable devices, and sterilized medical devices. The company says it will take innovations like this to fill our world with smart devices.

The memory chips are so efficient that they can operate on an extremely low levels of power. They can, for instance, operate on the small amount of energy generated by motion, so they can be used in a sensor chip that has no battery. The chips can consume 100 times less energy than other popular storage solutions without sacrificing speed and performance.

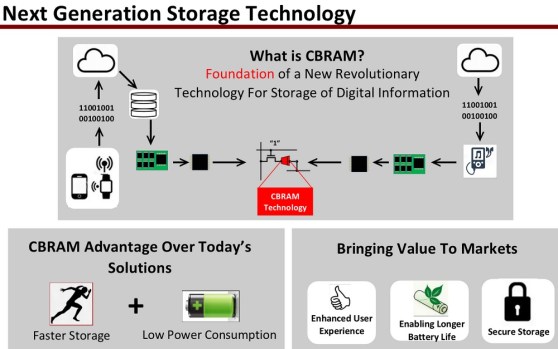

Sunnyvale, Calif.-based Adesto aims to compete with rival technologies such as flash memory with something that Adesto calls Conductive Bridging Random Access Memory, or CBRAM). These are programmable memory devices that can serve as standalone chips or be embedded inside other chips. Dubbed “resistive memory,” the Adesto technology could disrupt other forms of memory such as flash, which is ubiquitous in mobile devices.

The CBRAM technology is non-volatile, which means that, like flash memory, it can store data without the power turned on. But unlike flash, it can withstand threshold levels of gamma and electron beam sterilization treatments without any measurable loss or corruption of data. That means it can be used inside a surgery room in a hospital, even after sterilizing.

That, in turn, will enable a series of intelligent medical devices that can be used in hospitals and other sterile environments, said Narbeh Derhacobian, CEO of Adesto Technologies, in an interview with VentureBeat. Under the same sterilization procedures, flash memory would become inoperable. Medical devices will be able to store critical data and operate under ultra-low energy conditions if they use CBRAM, he said.

“Adesto is reinventing memory for the age of the Internet of things,” said Derhacobian. “The huge growth of Internet of things won’t happen if the components aren’t there to support it.”

Other chip makers such as Spansion are creating chips that harvest energy from motion, sunlight, and electromagnetic sources. That means the billions of sensors required to make smart devices out of ordinary objects — the Internet of things — could be self-powered. Without the need for batteries, those devices could operate for much longer, reducing overall costs for deploying vast sensor networks. And CBRAM is a key piece of that puzzle, since it can operate in battery-free devices.

CBRAM’s energy requirements for reading and writing data into memory are 10 to 100 times lower than flash. It works with Bluetooth Low Energy and other Wi-Fi platforms, and it has performance similar to dynamic random access memory (DRAM), which serves as the main memory of most computing and mobile devices. It can write data into memory using 0.6 volts, compared to about 10 volts for flash. It stores just 1 megabit of data, which is far less than many computing applications. But it is plenty of storage for Internet of things sensors.

“I think the memory world will be turned upside down when the growth for the Internet of things happens,” Derhacobian said.

Above: CBRAM

The CBRAM tech stores digital ones and zeroes, the code of binary computing, in typical memory cells. You put an electric charge into a capacitive cell to store the data. A non-volatile cell will retain the bit stored in it, even if the power is off. It typically takes a lot of energy to do this. By making a change to the manufacturing process that adds what is known as a “dielectric layer,” a small electrical voltage can change the resistance of the memory cell. It can alter the resistance to high resistance or low resistance. That’s how you can distinguish the difference between a one and a zero.

Competitors such as Hewlett-Packard have announced “memristor” technology that has similarities, but Derhacobian said his company is the only one shipping today. It started shipping last year, and it has shipped more than a million chips to date.

Across the medical field, applications include orthopedics, smart syringes, and sample containers along with surgical devices requiring sterilization before re-use, as well as many future applications.

Early on, it wasn’t easy to get electronics companies to pay attention.

“A lot of companies claim they have had groundbreaking memory technologies, but we are the only ones shipping resistive RAM today,” Derhacobian said. “This kind of change happens rarely, about once every 30 years. We have real, tangible products. I meet with customers and I leave samples with them.”

The chips are small and low cost, taking up about 2.5 millimeters squared in terms of die size. That’s about half the size, and therefore, theoretically, about half the cost of similar solutions in the market that operate on much higher power. (A chip’s size is directly related to its cost and manufacturability).

Adesto was founded in 2007, and it has been granted more than 100 patents. It created a demonstration for the Department of Defense’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which was experimenting with wearable health sensors for soldiers. That demo chip was powered by the motion of the soldier’s arm, so it needed no battery.

Adesto already has more than 300 customers, including top tier consumer electronics companies. The venture-backed company has more than 100 employees and is profitable, Derhacobian said. In fact, Adesto’s gross profit margins are about 45 percent, and typical memory vendors have about 25 percent gross profit margins. Among the investors is Applied Materials, the world’s largest maker of chip-making equipment. Other chip companies who are investors have a collective market capitalization of more than $40 billion. (They don’t want to be identified.)

The company invents the technology and has manufacturing partners, known as chip foundries, manufacture its devices. The proprietary memory solutions can be used in consumer, communications, mobile, and industrial applications.

“We are very well positioned to be the player in memory that supports all of the growth people are predicting,” Derhacobian said.

Above: Adesto