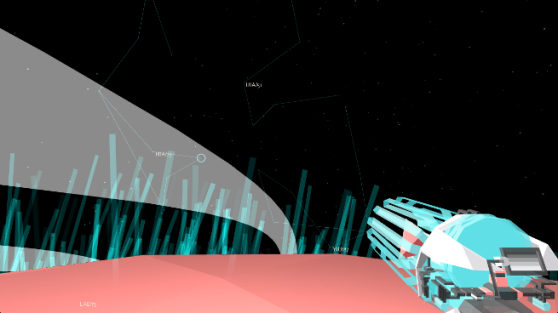

An electronic cyberart trend has been bobbing in and out of the video game psyche for the last two decades, and it’s seeing an upswing with modern independent game developers. Games like MirrorMoon EP, Race the Sun, Fract, and Smash Hit have adopted this low-fi movement’s visual genetics and have ensured its influential spread to another generation of players. Like the current explosion of the retro inspired sprite movement, its simplicity makes it convenient for developers working on a small budget looking for a quick turn around from the prototype stage to final product launch. In exchange, it commands an art direction that is purposeful, with an intent that is honestly crafted.

It’s a style that gaming culture introduced to mainstream audiences in the early ’80s, but its exposure was not tied to a video game per say, but more a movie about video games: Tron.

Tron’s legacy is best known as a major introduction of 3D computer graphics technology in feature film special effects. For many, it was also an early glimpse into a new abstract fantasy world of cyber-consciousness, a world where rudimentary electronic building blocks would try to imitate real world objects in electric color. This visual style, however, wouldn’t pick up in video games until at least a decade later, when the capability to create real-time graphics out of primitive 3D polygon models would become more accessible.

One of the biggest video game influences of this style came out of Sega’s last big development renaissance in the late 1990’s, with the release of Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s Rez on the Dreamcast. We can cite games that used this art direction before Rez, but these didn’t resonate with developers and players to the same degree. When I ask people to name this visual style, the same two descriptors come out of their mouths: Tron-like and Rez-like.

Curious about the recent growth of this art style within games, I’ve reached out to four indie developers who have all created vastly different interactive experiences from each other, but whose art direction shares this very distinctive low-fi 3D cyber look — and asked for their perspectives on this fascinating visual style. In part one we’ll cover a little bit of naming convention and art history, then dive right into the distinctive visual characteristics of this art direction.

Digital futurism?

While I was digging for information on this style, it surprised me that I did not run into a term for it. Referring to this art style as “Tron-like” and “Rez-like” is too informal and sloppy. It needs a name. I eventually had to scrape by with a few discussions on the Internet, hoping someone had coined a good name for the style, which also disappointingly fizzled out without a solid recommendation.

Then I decided to coin a name myself, pieced together with two words that stuck out while combing for a proper term: “Digital Futurism”.

Those words resonate with what I feel a “Tron/Rez-like” art direction is. A few types of Futurism exist, but they all share a key element of being fascinated with the possibilities of forward-thinking designs, architecture, and ideas. Tron also employed several concept artists who were heavily influenced by the look of the original movement, including Syd Mead who is a famous concept artist for other Futurist influenced films such as Alien and Blade Runner (and is coined as a “Visual Futurist”).

Where futurism tends to be occupied with the “could be one day” technology of the real world, our subject concentrates on what a high tech vision of the future may look like inside the rules of a digital universe — hence a vision of “Digital Futurism.”

Unfortunately, Futurism has a political and social problem. The earliest version of the movement originated in Italy during the early 1900s by poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who linked Futurism to the fascist ideals of the time. Although Futurism celebrated the imaginative visions of a future built off of ingenuity and speed, it also had very strong opinions about how to get there, who should benefit, and by what means. Marinetti glorified war as a great cleanser of society and violence as a positive tool of oppression.

One of the participants in this discussion, Pietro Righi Riva of Santa Ragione (creator of MirrorMoon EP), had his own perspective on my use of the term, “Personally and being Italian, we wouldn’t like our work being called a ‘Futurism’ because that art current had some strong social and political connotations that are very much in contrast with what we believe in. And even some of the themes of Futurism, [such as] strength, violence, power … are not things that are really present in our production, nor part of our philosophy as authors. Although Fotonica, our first game, was very much about speed and vertigo, it was so in a way that did not glorify strength and power, but rather tried to capture levity.”

“Futurism is something that is part of our cultural background of course,” Righi Riva explains, “but mainly for the aesthetic contribution to painting and visual imagery in general along, together with other European movements like Cubism … they [Cubism and Futurism] had in common the way they both tried to represent different perspectives and moments in time on a single canvas.”

Righi Riva sees the art style from a different angle and suggests a slightly different name, “The term Futurism kind of evokes an idea of visions from the future, while low-poly would be more of a retro-futurism, since it evokes the early days of computer graphics and certainly not what we imagine games to look like in the future. So Digital Futurism can be a little misleading, not quite fully communicating that digital low-fi art style you are referring to.”

Righi Riva brings up several good points, aside from just the darker political side of Futurism, and I respect his perspective on the topic. For the sake of clarity, however, the other participants and I refer to the art style as “Digital Futurism.” Perhaps beyond this article, a discussion can be continued and we can try to find a better name for this visual style?