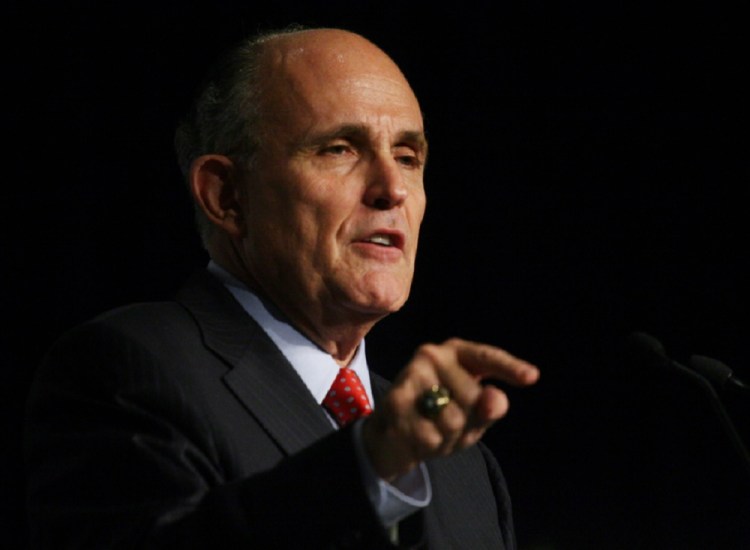

Activision knows something about firepower. After former Panamanian military dictator Manuel Noriega sued Activision Blizzard for using his image without paying him royalties in 2012’s first-person shooter Call of Duty: Black Ops II, Activision rolled out former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani as its lawyer to defend the lawsuit. Giuliani, a former U.S. Attorney and former First Amendment litigator, moved to dismiss Noriega’s lawsuit yesterday — which also indicated that Noriega was portrayed in a negative light — as absurd.

Activision Blizzard makes more than a billion dollars a year in revenues from Call of Duty games, which are played by about 40 million people. But the company is also fighting for the legal right, which it says is guaranteed by the First Amendment, to create fictionalized stories around real-life characters.

Giuliani explained his stance and why he got involved in the case during a press conference on Monday. Activision said in its documents that the stories in the Call of Duty franchise, like many movies and television shows, are ripped from headlines. From the Cold War to World War II and the advanced soldiers featured in the upcoming Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, the series is fictional but grounded in reality. Call of Duty regularly features characters that are ruthless dictators and iconic villains, such as Fidel Castro and Manuel Noriega, as well as vaunted heroes such as President John F. Kennedy.

Here’s an edited transcript of that press conference.

Rudy Giuliani: Thank you for joining the teleconference. This is Rudy Giuliani. I, along with several other lawyers, represent Activision in this case. My law firm is Bracewell & Giuliani.

For me, this case is a very important one because it’s extremely damaging from the point of view of an attack on free speech. Video games are entitled to exactly the same protection as movies and books under the First Amendment, according to the United States Supreme Court decision in 2011. To attack, in this way, by Noriega, in order to obtain millions of dollars on a theory of publicity, would open the floodgates to numerous historical figures, infamous and otherwise, to bring lawsuits against video games, movies, and books in which they are mentioned.

This would allow Osama bin Laden’s heirs to sue Zero Dark Thirty for the portrayal of Osama Bin Laden in that movie. I could go on and on and give one example after another of the numerous movies and books in which historical figures are used, sometimes in a fictional way and sometimes not. In this particular case, Noriega is used in a fictional way.

The second reason that I’m very upset about this lawsuit and involved in it is because I’m outraged that Manuel Noriega, a notorious dictator who’s in prison for drug dealing, for murder, for torture, is upset about being portrayed as a criminal and an enemy of the state in a game called Call of Duty. Quite simply, it’s just absurd. I’m not interested in seeing our courts give handouts to criminals like this. Noriega has already extracted hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars out of the United States in drug money. I can tell you that from my experience as Associate Attorney General and United States Attorney in the 1980s. To allow him to seek millions of dollars in damages that he can take down to his Panamanian prison is an outrage.

That’s why we’re defending this case with great vigor. It could create a terrible precedent that could go well beyond just video games and extend into movies or books. It could also put in jeopardy the whole genre of historical fiction, which is one that is growing, that’s a very important art form. It happens to be one I enjoy immensely. I read many books in which I see presidents, CIA directors, FBI agents, and sometimes even me portrayed. Sometimes accurately, sometimes inaccurately. But we’re public officials, public figures. In the case of Noriega, he made himself a public figure. This is not a person who was the victim of a crime who was thrust into the public spotlight. This is a man who, through his activities, some of the most heinous activities in history, made himself one of the most infamous people in the world. He should have to expect that he will be included in novels, in movies, and in video games.

The last point is, when you hear about this lawsuit and you think about it, the impression is, “Oh my goodness, Noriega must be a very big part of this.” The fact is that Noriega is not a very big part of this Call of Duty video game. He is a bit player. He is only one of 45 or more characters. He is in only two of 11 segments. He’s in about 1 percent of the overall game. And most important, he’s not even advertised as a featured player in the game. In other words, he hasn’t been used to market the game in any way, which is very different than some of the other cases that have occurred in the past.

For all those reasons, we believe this is a very important case, and we believe this is a classic case of evil versus good. This is an evil man — I don’t think that’s at all exaggeration — suing a company that is a good company, a company that employs 7,500 people, that’s given millions of dollars to veterans’ causes, that’s helped to find jobs for more than 5,000 veterans. Forty million people play this game. This is an extremely popular game.

As I said before, this is no different from Osama bin Laden going after the movie Zero Dark Thirty. There’s no difference in going after a video game, a movie, or a book. It’s offensive. It’s absurd. We very much hope that the judge dismisses the case based on the anti-SLAPP [a state law protecting free speech] motion which we filed today in court in California.

GamesBeat: Why has Activision taken such a high-profile response to this? If the case is so absurd, it seems like it might be easily dismissed. Is there some reason you’re bringing out more firepower to oppose Noriega on this?

Giuliani: The reason for that is, whether it’s our opinion that it’s absurd or not, all cases that are brought in court have to be taken very seriously. On the free speech aspect of this, there is a great deal at stake — not only for the video game business but also for the movie business and the publishing business because of the broad nature of the principle involved. That’s the reason why such seriousness is being given to this.

I’ve found, as a lawyer for many years — I was a lawyer for many more years than I was a mayor — that these cases should never be taken lightly. This attack on Call of Duty could have a chilling effect on all works of art — movies, TV, books. For the time that it exists, it will have a chilling effect. The attempt here is to try to get this dismissed as fast as we can. But given the court system, you can’t guarantee that anything is going to be dismissed quickly. Any lawyer that guarantees a result is a lawyer you shouldn’t have.

This has implications for Saturday Night Live, with their portrayal of public figures all the time, or for the movie Forrest Gump, or for the movie The Butler, in which President Nixon was depicted, in which President Reagan was depicted, in which Mrs. Reagan was depicted. There’s a lot riding on this. We think this is absurd because of the nature of the person who’s bringing it, but there are still very important legal principles involved. We take it very seriously.

Question: You’ve been criticized, when you were mayor, over free speech issues, notably the Brooklyn Museum’s exhibit, the Sensation exhibit. Has taking up the mantle of free speech here caused you to reconsider your opinions in that case?

Giuliani: These are two different things. First of all, I should tell you my background, long before I was mayor. I used to be a First Amendment lawyer. I was part of the law firm of Patterson, Belknap Webb & Tyler. I represented the Daily News, the Wall Street Journal, and Barron’s in a number of cases. One of the most famous was Nemeroff against Abelson, which set a precedent you don’t want to be bored with now. This kind of case brings me back to what I used to do in the 1970s when I was a partner at Patterson Belknap.

My position on the Brooklyn Museum had nothing to do with the First Amendment. I was more than willing to protect their right to exhibit of — I think the work of art was cow dung that was spread on a picture of the Blessed Mother. Although I disagreed with it and found it offensive, I was more than willing to allow them to do that and have the police protect them if that was necessary, which I did many times with things I disagreed with. What I didn’t want to do is give them city money in order to do that. I didn’t think the city should have to pay for that. That was a question of the use of city money, not the First Amendment.