HUNTINGTON BEACH, Calif. — You might not think investors with huge piles of money would have much to worry about, but that’s increasingly the case in the competitive world of tech venture capital.

There is so much money chasing so few good deals that VCs need to work hard to get the choicest opportunities.

One way is by offering ridiculously huge valuations, such as the $1.12 billion that Slack is now worth — even though it has only 268,000 daily active users. (It’s important to note that, thanks to Slack’s freemium business model, these are not all paying customers.) That means Google Ventures and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, the lead investors, are valuing each Slack user at about $4,180. If Facebook got a similar valuation for its billion-plus users, it would have a market capitalization over $4 trillion.

For Slack’s founders, that’s a great deal — they got $120 million in operating capital and only had to give up about 10 percent of the company. For other VCs, it’s probably causing sticker shock and making them wonder how they can ever compete.

So if you’re a VC and you don’t want to pay top dollar just to get in on a promising new startup, you need to get creative.

“The venture model is evolving to a value-add [proposition],” Intel Capital president Arvind Sodhani told me this week at his company’s annual conference for portfolio companies and partners.

Intel Capital — the venture arm of the semiconductor giant — has pockets just as deep as Google’s or Kleiner’s. It has invested $300 million to $400 million every year for the past decade, making it one of the largest funders of startups in the tech world. In 2014 so far, Intel Capital has made 55 investments totaling $344 million. It has also seen three IPOs and 19 acquisitions among its portfolio companies.

But it’s not just cash that Intel Capital offers: For the past decade or more, Intel has offered a powerful “ecosystem” in addition to its capital. Taking an investment from this fund means gaining access to a powerful network of potential customers, partners, advisors, and peers. This week’s Intel Capital Global Summit, here in sunny Southern California, is the capstone.

About 1,000 people attend the event, roughly half of them the CEOs and executives of “I-Cap companies,” as the portfolio companies call themselves. The rest are Intel employees or representatives of Intel partners — plus a smattering of journalists. A lot of dealmaking gets done in the hallways.

(Intel even brought Beastie Boy DJ Mix Master Mike to put on a private show in the evening — another amazing perk that, curiously, most attendees seemed not to appreciate.)

In short, an investment from Intel means admission to an elite club of companies, with access to many other companies that can purchase your products, invest in you, or help you in other ways. It really is an ecosystem, with Intel at the heart of it.

“Here I can meet lots of CEOs from completely different fields — but they have the same problems,” Idan Tendler, the CEO and founder of security analytics startup FortScale told me. (FortScale took $10 million from Intel Capital and Blumberg Capital in June 2014.) “It’s great networking. If I want to reach a customer or a partner, I can do it here.”

Other funds are taking a different tack. Eden Shochat is the founder of Aleph, an Israeli VC firm that has raised its first fund, with $150 million committed. In other words, Aleph’s entire fund is about half of what Intel invests in a single year — and the network of Israeli entrepreneurs and investors, while powerful, is much smaller than Intel’s ecosystem.

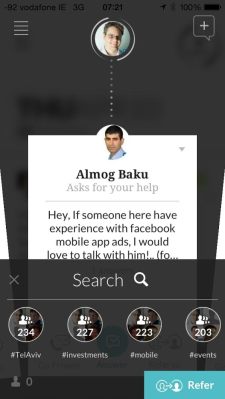

So Aleph is differentiating through software. It has built an app, which it calls Karma, to help connect Israeli entrepreneurs with one another. It’s an open network, so it’s not just for Aleph portfolio companies. Using the app, people can ask questions, receive or give advice, and make referrals to other people in their network.

Karma now has 2,100 entrepreneurs using it, Shochat says, which is a substantial fraction of the Israeli tech startup world. Shochat says that this app provides real value to entrepreneurs — but it also gives Aleph unprecedented visibility into where the talent lies. For instance, it’s easy for him to see which users are continually receiving referrals, which provide the best answers to startup questions, and which have the best reputations as engineers, designers, or what have you.

It also provides a way to funnel deals into Aleph’s pipeline.

“You will always have too few partners — so you need software to get the right deals to the right partners as quickly as possible,” Shochat told me.

But for startups, that software is an added value that, he believes, will make his firm more attractive than others. And, Shochat believes, VC firms have moved too slowly to embrace the power of the software that they ostensibly believe in.

“It’s interesting to see that the industry tasked with identifying innovation is still working with IT systems from the Stone Age,” Shochat said.

That might be a bit harsh. But one thing is clear: As long as valuations are this high, and the market remains this optimistic, most VCs are going to have to work quite a bit harder to keep (or win) their places at the table.