For all the big names and conversations at the Web Summit in Dublin this week, the most interesting thing about the event was the Web Summit itself.

Virtually every attendee could recite the following statistics: The Summit has grown from 400 attendees in its first year to 22,000 in its fourth year. Much of the conversation at the Summit revolved around how big it had grown in such a short time — and whether or not that was a good thing.

Much of the credit is typically given to Summit cofounder Paddy Cosgrave, 31, who grew up on a farm in Ireland and somehow managed to convince some of the most notable entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley that being in Dublin once a year is a can’t-miss event. But from the start, attendees have also praised the quality of the networking and connections they made on the Summit’s pub crawls and evening events.

As it turns out, those connections were more than just serendipity. They were engineered by Cosgrave and a friend using a basic algorithm to sort people into pub crawl groups in the first year of the Summit. With the size of the conference increasing massively, Cosgrave has made a big investment in hiring data scientists, physicists, and statisticians as part of the 100-person team that works full-time on producing the conference.

Cosgrave said the goal is to continue to increase the value of the networking at the conference. But on a broader level, he’s hoping to disrupt the conference business itself.

“The software you use when you go to a conference is the software you’ve been using for years, your eyes and your mouths,” Cosgrave said in an interview. “The idea that there isn’t effective software you can just fire up on your phone saying you should connect with this person and this person at a conference is shocking. This should exist at this point.”

As the conference has become gigantic, rethinking the way people connect has become even more critical for Cosgrave and his team.

The Summit this year included 10 stages, running talks simultaneously for three days. There were 614 speakers and 2,160 exhibitors. Stages were spread across two sections of the Royal Dublin Society’s fairgrounds that require a 15 minute walk between the various stages. And on top of that, there were dozens of social events being held across the city every night, often until the early morning hours.

“Every morning I would roll out of bed and scroll through Twitter and see all the kebab selfies people were taking at 6 in the morning,” Cosgrave said. “And I’d think, oh my goodness, these people have to be back at the Summit in just a couple of hours.”

Still, the chances of randomly meeting just the right people is much reduced as the size expands. So Cosgrave has tried to take the randomness out of the equation.

His hires this year included Cian Kennedy, the Summit’s vice president of quantitative strategy. As described in his hiring announcement: “Cian’s one of those rare super quants to jump from the world of high finance in London to tech in Dublin. He spent eight years with JP Morgan, managing a worldwide team focused on high volume algorithmic trading.”

In June, the Summit hired Michael Sexton and Louis Burke. Sexton is a physicist who specializes in computer simulations. Burke’s focus is machine learning and cognitive science.

Sexton and Burke are overseeing a project at the Summit that involves installing hundreds of GoPro cameras throughout the venue to record every aspect of the event. The pair will then run a deep analysis of the footage to measure things like crowd flow, choke points, volume and length of interactions, and visits to exhibitor booths. The idea is to discover what inspires or prevents interactions.

Cosgrave said lots of big corporate retailers already conduct such projects. He’s just applying it to the conference business.

“So that the customer, in our case the attendees and exhibitors, gets a better experience,” he said.

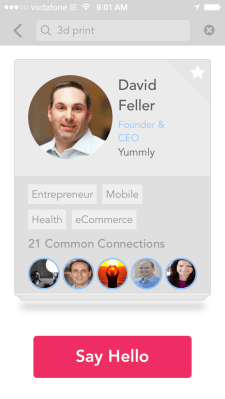

Summit developers built a special search engine (with the help of a company called PeopleGraph) for the conference called Wholi. Attendees could enter a name or a topic like “3D printing” and Wholi would search the profiles of other conference attendees and exhibitors.

Cosgrave’s developers also built a mobile networking app for the conference this year. The app scans attendee and exhibitor profiles and suggests potential connections. There is a chat feature for people to contact each other directly. Cosgrave once described it as Tinder for conferences.

Cosgrave said they released an updated version of the app after the conference started that increased the number of daily recommendations from 50 to 300 based on feedback they were getting from attendees.

“It’s a reflection of how important networking is to people who have come here,” Cosgrave said.

The team was also using algorithms before the conference to connect startups and investors. The Summit used programs it developed to sort pitches and slidedecks from startups and funnel them to relevant venture capitalists.

And now that the event is over, Cosgrave said the networking will continue. He said that the apps and algorithms are learning more about people’s interests as they use them more. The Summit is going to use that knowledge to send followup emails and notifications to exhibitors and attendees to suggest other people they might want to try connecting with after the event.

Despite all these efforts, not everyone was pleased with the increased size of the conference. There were plenty of complaints about it being too chaotic — too many people, too many talks. Compounding the problem was the conference’s Wi-Fi system, which only seemed to work sporadically, creating a technical hurdle to some of the networking efforts.

The Wi-Fi is controlled by the venue and not the conference. Cosgrave has said that organizers will have to consider whether the infrastructure can be improved or whether the event will have to leave Dublin. Given that the Irish government estimates the economic impact of the conference to be $130 million, that seems unimaginable.

At the same time, Cosgrave was also aware that the conference’s size had taxed the entire city of Dublin. What started with one pub the first year has now taken over 30 in the city center at night. And taxis, buses, and hotels seemed to be scarce.

“I think there is an upper limit to Dublin as a destination,” Cosgrave said.

To that end, the Summit is expanding to the U.S. next year. It will host an event in May 2015 in Las Vegas called “Collision.” Cosgrave said it will start small, but he hopes to grow it quickly. And the Summit will be deploying many of the same technological tools and lessons it has picked up in Dublin.

Overall, it’s just the next step in his bigger ambition to disrupt the conference business.

“I don’t think for one moment we’re coming close to delivering significant value at this scale,” Cosgrave said. “But we’re giving it a shot. We’ve made things maybe one percent better. And if we can build on that, we think we can have a big impact on the experience people have at conferences.”