NEW YORK — Over the summer, highly regarded New York software development shop Fog Creek Software spun out Trello, a product that a couple of developers had cobbled together three years earlier to help people keep track of what they have to do. Now Trello is taking off in a big way.

Fog Creek helped the new startup pull in a stockpile of venture capital and made sure Trello was outfitted with its very own corporate swag. But why now? And what made Trello so different from Fog Creek’s other developer-centric products, like bug-tracking system FogBugz and source code-hosting software Kiln?

It all happened because the people behind Trello and Fog Creek believe Trello really could be the next big thing, not just a tool programmers use to remember what they have to work on.

“It depends, really, on whether the product has the potential to be gigantic,” Joel Spolsky, a founder of Fog Creek and an influential figure in the world of software development, told VentureBeat in a recent interview.

Ultimately, Spolsky and Fog Creek cofounder Michael Pryor felt that all signs pointed to a spinout, just as Stack Exchange, which built the technology for popular developer Q-and-A site Stack Overflow, had become its own venture-backed company.

With enterprises volunteering to sign deals for company-wide access to Trello, the decision to turn Trello into a separate outfit now looks pretty smart. The site now counts more than 5 million users, and people use it for tracking job applicants, handling support tickets, and even planning weddings.

Spolsky and Pryor, now Trello’s chief executive, have hinted that they’ll be adding some tantalizing new features to Trello, like automatic card ordering and list sorting — or the ability to use Trello on mobile devices without Internet access.

“You’ll be able to do that, I promise you,” Pryor told VentureBeat. “Just give us a little bit of time.”

In the beginning…

The story of Trello begins in 2011. A pair of Fog Creek developers, Bobby Grace and Justin Gallagher, wrote a prototype for a web application that gave a high-level overview of what employees were working on. Because, at least according to Pryor, people were using sticky notes to do this sort of thing.

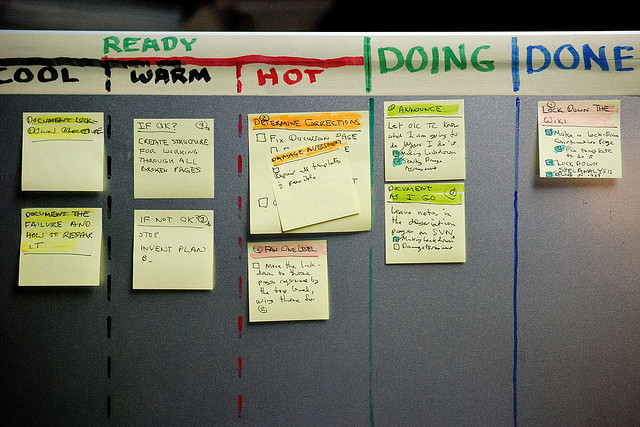

“If you went into any software-development company, you would see people would have a whiteboard up, and they would have Post-It Notes all over the whiteboard in columns,” Pryor said. The structure also drew from a process called Kanban that originated in Japan more than 50 years ago.

But Spolsky wanted the new product to be simple. He initially capped the list of tasks in the experimental software to just five items — after all, you could only put so many sticky notes on a whiteboard.

“Everybody published a list of five things: two things that they’re working on now, and they could switch between them if they get bored; two things that they would do if they finished those two things; and one thing that they promised everybody they would never work on … [that is] such a bad idea, but they would never stop talking about it,” Spolsky said.

If you had 10 people on the team, that would give you 50 items altogether. But at least you didn’t have so many things going on that it would become overwhelming — like what happens when you get too much email.

If you have too many items, said Pryor, “You just declare bankruptcy, and you’re like, ‘I’m deleting all my messages and starting over.'”

The Kanban style, with several columns that could each store cards, provides a clean and simple format for tracking work in progress. But Kanban isn’t necessarily familiar to non-developers.

“When we built it, we were like, this tool is for everyone,” Pryor said. “It is not going to have a single software-development word in it. It’s not going to be [only for] programmers.”

And so, from the beginning, it was built to be a simple, almost playful application that you can adjust easily whenever you want.

Spolsky said he was looking for something with the same kind of simplicity and playfulness as Microsoft Excel.

Yes, Excel.

Spolsky himself used to be a program manager on the Excel team at Microsoft. To hear him tell it, Excel was more forgiving than modeling software from other providers when it came to making calculations based on formulas. “They required, like, such rigidity,” he said. And Excel leaves room for random notes and lists, which, of course, Trello does as well.

Spolsky suspected the people building Trello — at the time, it was called the Trellis team, reflecting the concept of bringing structure to a workflow — might have built something useful when he heard they were “using it for their own stuff,” even though, at the time, the application was pretty bare bones; it had just 900 lines or so of code.

At some point, the just-five-things concept got dropped, letting people put as many things on their boards as they wanted.

And at the TechCrunch Disrupt conference in San Francisco in 2011, Trello formally launched, with Spolsky walking people through a demo.

The Trello cult forms

Within six weeks, there were more than 100,000 users. And for the next three years, during which programmers kept adding features to Trello — with many of them getting thrown into a sidebar that users can hide with a click so as to keep things simple — Trello ran exclusively with Fog Creek’s own money.

“We’d start to see people writing blog posts about it that we didn’t ask them to write about it, like, ‘This is how we use it at UserVoice,'” Pryor said. The usage was mostly coming from tech-savvy companies, but gradually people were beginning to use Trello for things other than monitoring software development work.

As the use cases become more complex, companies might well graduate to full-on customer-relationship management or applicant-tracking-system software. That’s fine with Pryor, because, he said, they’ll eventually have other problems they’ll use Trello to solve. In other words, at least in Pryor’s mind, there’s always a place for Trello.

All the while, as usage was growing, the venture capitalists were calling, Pryor said.

In mid-2013, Fog Creek introduced Business Class, a premium tier of service with special features for admins. With that in place, it was possible that Trello could survive and even thrive without external money.

“But we saw there were so many different things that we still wanted to do, like localization, offline mode — like, there were just big projects that we needed to do, and for Trello to really get ubiquitous and just everywhere, we finally relented and let the VCs invest,” Pryor said. “And that just made it a little bit easier for us to postpone really spending too much time worrying about the revenue.”

Today, Pryor said, Trello has “lots of enterprise customers,” just two months after Trello hired its first salesperson.

Multiple teams inside of companies use Trello for various purposes, as it’s free. And that is a sales lead.

“We can just go to that company and say, ‘Hey, did you know you have 3,000 people using Trello?'” Pryor said. “‘Let’s get you all just paying one invoice.'”

The viral spread of software across a large company is a never-dying trope in the domain of enterprise software. But when Pryor says it, it’s actually believable. At the moment, it does seem that Trello has the same kind of growth mechanics as Dropbox, in the sense that it’s free, becomes popular organically, and eventually gets bought by big companies.

The Trello people have realized this. And they have chosen to take venture capital — despite Spolsky’s historical criticism of that approach.

Not for everyone

Venture capital doesn’t make sense for the average business, if you ask Spolsky. It’s only appropriate for a small percentage of all businesses. “It’s almost like a tool that you might use in business in a particular set of circumstances to help accelerate the business,” he said.

A lot of people don’t understand that, though. Startups with venture capital get a disproportionate amount of attention in the media, thanks in part to the marketing and public relations that the extra money can buy.

And that’s to say nothing of the possible downsides of taking venture capital, like obstructing the development of corporate culture, as Spolsky has pointed out on his long-running blog, Joel on Software. As Spolsky wrote in 2003, “When people ask me if they should seek venture capital for their software startups, I usually say no.”

But this time it’s different. In the case of Trello — and earlier, in the case of Stack Overflow — Spolsky and Co. sense the chance to Get Big Fast. Trello’s expansion within companies has proven that lots of categories of people are getting value out of it. In short, the market is large. So instead of chasing profitability exclusively by accepting revenue from a small number of happy users, it’s reasonable to think bigger.

“The very fact that Trello is pervasive and everybody, certainly in the startup community, is using it all the time means that it’s a great way to collaborate,” Spolsky said. “So that’s the kind of business for which VC is appropriate.”

Hence the $10.3 million round for Trello from Index Ventures, Spark Capital, and various angel investors.

And as for introducing ads to Trello in order to help cover the costs of the free tier?

“I don’t think we’re ever going to need to,” Spolsky said.