LucasArts is dead, but one of its best composers, Peter McConnell, is doing just fine.

After starting his career in video game music by working on classic LucasArts games like Outlaws and Full Throttle, he became famed game designer Tim Schafer’s go-to man. He’s worked on Double Fine games like Psychonauts, Brütal Legend, and Broken Age.

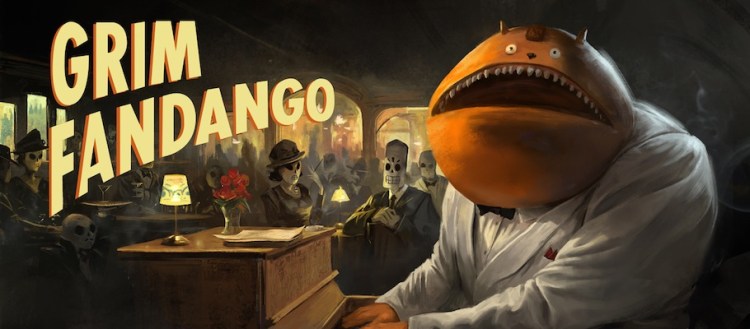

However, his most famous score might be the one he created for the classic adventure game Grim Fandango in 1998. Another collaboration with Schafer at LucasArts, the music features a unique blend of classic noir soundtracks, swing, and Mexican folk. Now, thanks to the recently released Grim Fandango Remastered, McConnell had the chance to improve his famous score with new orchestrations.

We were able to chat with McConnell about the remastering process, as well as discuss his work on the original Grim Fandango soundtrack and his early days at LucasArts.

GamesBeat: When was it decided to re-orchestrate the score for Grim Fandango Remastered? Was that a pretty early decision?

Peter McConnell: In my mind, it probably happened about the time the game was originally released. I was always very proud of one aspect of the score, which was that we were able to do nice live jazz recordings for a game in 1998, which was — in those days, that was not very common. We were able to do a really nice job with some super-talented Bay Area musicians. It was just really fun. I look back at the folks who played on the original tracks, it’s just awesome. Bill Ortiz, who now plays with Santana. Derek Jones, the bass player, has played with all kinds of folks, from Jay Leno’s band to — I was lucky to get this guy Ralph Carney, not to sound like a name-dropper here, but he’s Tom Waits’s main lead player. Just a really awesome collection of folks. Hunt Christian, the cello player, he’s a new-age artist. He tours all over the country. Anyway. Just a fantastic group of folks.

So there was this aspect of the score that I was really happy about. And people loved it. There was definitely a recognition of it when the game came out. Whoever heard of doing swing in a film-noir game about skeletons? So in some sense, it felt sort of like a gift at the time. But there was still an aspect of the score that I was really — two aspects of the score that are similar, that just inherently bugged me going out the door. One was, there just weren’t enough sample sounds. Some of the aspects weren’t that convincing. In particular, number two, the orchestra was done with what at the time were decent samples, but it just didn’t sound much like an orchestra. So you had this one aspect of the score that was really getting across the vibe, really convincingly, and then this other aspect of the score that was … kind of pretend? Like, “I’m not a real score, but I play one in a game.”

Whenever I would listen to that music, I was like, wow, this is pretty nice writing. I wonder what it would really sound like. It’s always bugged me a bit, in the sense that Grim’s music was a little bit ahead of time, but it suffered in a way that things do when they’re ahead of their time. The pipeline isn’t quite ready to do it. Not that long, a couple of years after that, people started doing a lot of full orchestra scores. You couldn’t do it at the time. But it wasn’t a long time before that was a feasible idea. The bottom line is that I’ve always wanted to do this. When I heard it was being remade, that’s pretty much the first thing I said. If you want to do something really great with this score, biggest bang for the buck is going to be to take those orchestral movements and record them live.

I was lucky to have a relationship with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra from working on Broken Age together. The music administrator there is a fan of the music, a backer of Broken Age. He’s done a huge amount of work to get everybody in MSO excited about doing music for games. Grim in particular was a tough job because as I said, I never expected that I would actually get the chance to do this live. So what I did was the best I could with those old samples. I tried to make the pieces sound as organic as I could with those limitations. One of the ways I did that was to be very free with the tempo so it would sound like a guy was conducting while watching the game, old-school movie style. No click track. You look up there and see the screen and you’re sitting there waving a baton and the orchestra’s just going with you. That feel, for those out there who work with sequencers — a sequencer is a tool you use to write music with — I wasn’t paying any attention to bar lines. I was just playing music. It was too much trouble to change the temp to make it follow to what I was doing as I was playing. I just wanted to make it sound very musical.

So it was extremely organic. Not quantized. These are all terms for people who do this stuff. As a result, when we came back to it, I looked at it and said, “Oh my God, I would never do this today.” I’d never have the tempo move around like that. How are these guys gonna play this? It was a real job to capture, to make sure that the music didn’t change. It was a real job to break it apart in sections and make it achieve all the fluidity, which because of the dynamic nature of the music — in order to do that, we had to break it up in sections and record it bit by bit and assemble it later. It was a big task, I would say, for the orchestra and their fabulous conductor, Brett Kelly. And for me in terms of grabbing it all and getting it all to make sense, doing real bar lines in there. But it happened. Now I can say, that’s what it sounds like!

GamesBeat: So it’s not as easy as just opening a file and printing sheet music for them.

McConnell: No, it’s not. Anytime you’re doing this, you go through a process where you compose it by whatever method you do. Most people these days use a sequencer with samples. Some people still sit down at a piano to test things out. I do a little bit of work with pencil and paper. But I was definitely raised in a recording studio. Most of it I do with a sequencer. What the sequencer does — then you use ProTools, what they call a digital audio workstation. It’s a facility for turning what you play into notes. But it’s very crude. You have to work with it a lot.

When I’m working, I actually look at the score version of what I’m doing as I play it. Then I make sure that all the parts, the musical lines, are there, written basically well, in a notation program called Sibelius. I send that to an orchestrator to make sure that everything’s doubled right, everything’s marked with the proper dynamics. There are all kinds of things that you do there. Orchestrating is a fine art. Then, during the recording sessions, we’re sitting there watching what’s going on in Australia, making comments, and playing it again.