It’s harder making educational games than you might think.

The market for what are collectively known as learning games was worth $1.8 billion globally in 2013, and it’s expected to grow to over $2.4 billion by 2018. But revenue from selling to schools represents just a small proportion of those figures — $191 million in 2013, rising to $336 million in 2018. With no centralized educational sales platform and limited school budgets often tied up in red tape, it’s tough for dedicated educational game developers to turn a profit.

The U.S. government increasingly recognizes the value of educational games, and a grant scheme is helping encourage more development in this tough climate. Offering up to $1 million in funding, the Small Business Research Program at the Institute of Education Sciences helps support research and development into a variety of education technology products. Over the past 10 years, proposals for educational games have grown from just 5 percent of total applications to around 40 percent.

I spent time talking to three developers — including two who’ve received SBRP grants in the past — to find out what it’s really like at the front lines of the educational game scene right now.

Teaching 5-year-olds algebra

One of the most popular educational titles of recent years is one that’s struggling to find a place in schools. DragonBox Algebra is the mobile brainchild of Jean-Baptiste Huynh, a former high-school math and economics teacher from Norway. Huynh wanted a game to help teach his students — and his own kids — the bigger picture when it came to math, and he was hugely disappointed by what was already on the market.

“I didn’t find what I wanted,” he told me over a Skype chat. “There were almost no games where math was in the game mechanics. No games with something we can manipulate.”

That idea of manipulation is key to what Huynh wants kids to do with math. He strongly believes that they need to manipulate and play with math concepts in a physical way before they can begin to think about them more abstractly.

Hyun, along with Patrick Marchal — a Ph.D. in cognitive science — created the educational game studio WeWantToKnow and set out to build something they had no idea whether could actually achieve.

“We didn’t know at first we could create such a game,” said Huynh. “We did a lot of research and development — always trying to push the boundaries between entertainment and education.”

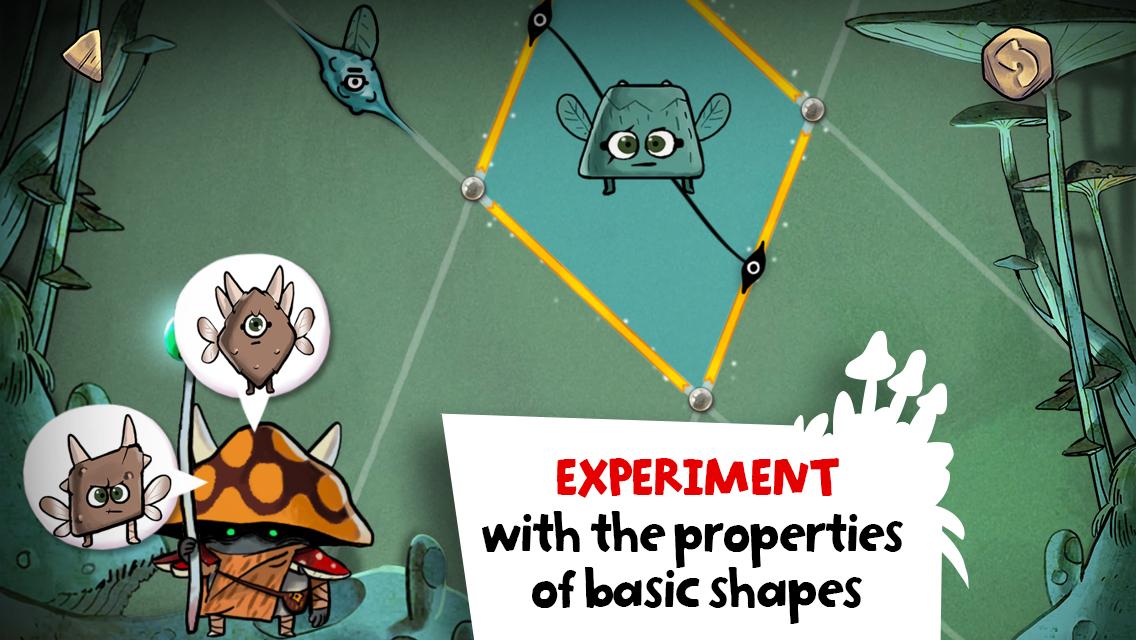

Hyun explained his design process, which WeWantToKnow has now transferred to three successful educational titles on Android and iOS — DragonBox Algebra 5+, DragonBox Algebra 12+, and DragonBox Elements — along with one work-in-progress, DragonBox Numbers.

“You don’t start with a story,” said Huynh. “You don’t start with dragons. You start really with pedagogy.”

“First, you take what you want to teach or what you want kids to learn, and you create what I call a digital manipulative. You design a virtual object with the characteristics, the features, of the real objects. Like in math, if it’s an equation you need to manipulate an equation. If you want to manipulate triangles, then you have to design a way kids can manipulate triangles. It’s an engineering problem.”

This logical approach to tackling a single area of learning can be replicated across different topics and subjects, according to Huynh, making it incredibly valuable. “That’s the beauty,” he said. “It could be applied to reading, coding — anything where you have a language and rules. With mathematics, the beauty of it is that it’s very consistent.”

DragonBox Alegbra’s top-down approach to big mathematical concepts lets kids as young as five tackle basic algebra. But therein lies the problem. Schools don’t want their 5-year-olds working on algebra; they want them learning the basics of the number system.

Educational freedom

Huynh says that freedom from the school curriculum is what really helps set DragonBox games apart, but he admits it’s then tough to sell the idea to schools without repackaging it. “The big problem in schools is we cut everything in small bits,” he said. “The reason we can innovate [at WeWantToKnow] is because we don’t pay attention to the curriculum. We are our own masters.”

But there are already forward-thinking teachers taking DragonBox Alegbra seriously, and Huynh is working on an adapted version of the game that’s more classroom-friendly.

In the meantime, WeWantToKnow is finding great success in the consumer market, having recently passed 500,000 downloads of its three premium-priced apps. Most of those sales have been to parents and homeschoolers, says Huynh, and the majority have come via word of mouth. “We are really lazy at marketing,” he said.

Huynh is especially happy that parents are using DragonBox Algebra to turn helping kids with their homework from a confrontation to a shared learning experience. It’s something I can relate to as a parent who’s battled with many homework assignments myself.

“With homework, the more you talk, the less they understand,” said Huynh, “and it destroys a little bit of the relationship between parents and kids. I want to replace this bad time with something of better value. As much as homework is a nightmare, learning with your kids is fantastic. One of the most beautiful things you can have in your family is when you learn something [together].”

I wondered if it’s even worth pursuing the schools market, given the success WeWantToKnow has had with direct consumers. “You have to be forward thinking,” said Huynh. “We’re in contact with Uruguay and they’re rolling out tablets to all kids [in schools]. France is going to do that from next year, too. You have a big hardware push for tablets and that means the market is going to increase dramatically because they will need the content. You will need really, really good content that works. It’s absolutely worth the investment because there’s going to be a huge, huge wave.”

Getting teachers to adapt

Getting tablets in classrooms is a great step forward, as it eliminates the compatibility problems of old PCs and Chromebooks, which aren’t really suitable for gaming. But teachers need to feel confident in the technology they’re being given and understand how best to use it.

“Traditional schools are still reeling from the fact that they have devices now,” said Dan White, founder of educational specialist Filament Games in a phone chat. “They’ve got this hardware and it requires an entirely new curriculum … and they’re still just trying to figure out what to do with these devices.”

Filament has benefitted from the Department of Education’s SBRP funding, and it’s created some impressive educational games — like Reach for the Sun and Crazy Plant Shop — as a result. Despite this success, though, White says that making teachers aware of the best games for their classroom is tricky, particularly as so many educational games look great but just deliver limited “skill and drill” opportunities to kids.

“That’s actually the premise on which our company was founded 10 years ago,” said White. “Our original slogan was, ‘Learning games that don’t suck.’”

“I’m honestly kind of astounded that in 2015 there’s still software that calls itself a game that is essentially a practice app with pretty graphics,” he said. “But what that tells me is that’s what a lot of teachers want. Whether they want it because they think it’s a good instruction tool or whether they just don’t have the literacy to really know what a good game is … It’s definitely one of those things.”