In the early morning of June 6, 1984, the residents of Shropshire County vanished. They left behind their pristine homes, farms, and cars after a mysterious event. In Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, it’s your job to figure out how they died.

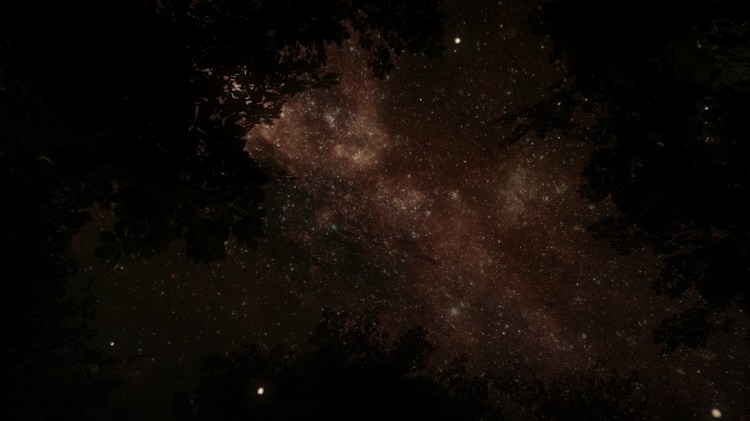

The PlayStation 4 exclusive (out on August 11) presents a postapocalypse you rarely see in video games. It’s not a radioactive wasteland filled with mutated monsters and zombies, nor is it a metropolis overrun with plants and animals. You begin in Yaughton, a small fictional town in the English countryside. The only living creatures to keep you company are insects and glowing yellow orbs.

With Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, developer The Chinese Room expands on the non-linear storytelling style from its 2012 game Dear Esther. Both are first-person exploration games where you piece together fragments of a fractured narrative. While Dear Esther’s short experience plays out like a poem, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture is more of a novella. Shropshire’s secrets, and the intimate lives of its citizens, are hidden throughout the town and its neighboring areas.

Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture has a heart-wrenching tale that few games can match. And it all starts with its fantastic cast.

What you’ll like

Shropshire’s residents

Though the people are gone, the cosmic phenomena now inhabiting the town immortalized their stories with traces of light. The orbs serve as your guides in the game, some of which even have names. While they can’t talk to you, they fly through the town and stop at areas you should visit. Heading to these places triggers a moment from the past, with the people appearing as apparitions made of tiny dots of light. You can listen to their conversations to get a sense of who they were and the parts they played in the story (see the video below for an example).

I found a priest welcoming the new girl in town, a couple arguing about whether they should find a way out of the quarantine, and others who just broke down and cried after realizing the end is near. Even though I couldn’t see their faces, those scenes were painful to watch. The trembling voices and the bouts of anger told me everything I needed to know about how they felt. It’s a testament to the character actors’ soulful performances.

But not every memory is depressing. I also saw teenagers celebrating their love despite what the girl’s father might think and a mother chastising her adult son for his taste in women. Love and how one chooses to share that love are some of the more grounded topics Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture tackles within its science-fiction premise.

These conflicts existed before the end of the world became a reality. But with their lives in danger, those feelings come bubbling back to the surface. The people have no choice but to confront them.

[youtube https://youtu.be/QjmkA2Wj0aU]Walking in their shoes

As in Dear Esther, the pace is slow. You can walk, but you can’t run or jump. It might feel unusual at first, but it’s necessary for the experience The Chinese Room was aiming for. It forces you to take your time looking for any important details in the town. And you’ll want to see every inch of it. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture has the most colorful postapocalyptic landscape I’ve ever seen. Shropshire is home to charming houses, gardens, brooks, and lakes — scenic views normally seen on TV or in European vacation photos.

Everything looks perfectly serene. The catastrophe struck so suddenly and violently that no one had time to lock their doors. I spent most of my time rummaging through homes and vehicles hoping to find more memories. As a silent and unnamed outsider, watching the residents’ last days on Earth is the only thing you can do.

When you’re not observing the light shows or listening to old radio broadcasts and telephone calls, a stirring soundtrack punctuates the eerie silence. Sweet, melancholic melodies often kick in as soon as a memory is over. They pick up where the dialogue left off, conveying what the dead can no longer feel: the anguish, the confusion, and the few fleeting moments of happiness. The Metro Voices Choir and London Voices Choir deliver powerful hymns with lyrics that could also serve as internal monologues for the characters. They’re an essential part of the story.

Recreating the apocalypse in your head

The memories aren’t shown in chronological order, so you must keep track of the different pieces of information and create the timeline on your own. At first it’s fuzzy, like a giant jigsaw puzzle with pieces that have indefinable shapes. But the more I learned about the people, the more the memories started to make sense. Conversations from the beginning of the game that didn’t seem important at the time became relevant once my knowledge of the characters grew.

I followed along as best I could by recording video clips of the conversations to my PS4 and writing a rough sequence of events on my phone. I developed an obsession over pinning down the relationships between characters and creating their family trees. Yaughton has so much history it almost feels like a real place. I wasn’t able to fill in all the gaps, so I probably missed a few scenes somewhere. But by the end, I had a decent idea of what was going on.