The stereotypes of women in gaming have been with us for a long time. They’re often depicted as princesses who need to be rescued or overly sexualized objects. But Marla Rausch, the chief executive of motion-capture business Animation Vertigo in Irvine, Calif., has witnessed a change in recent years.

Her company helps create the ultra-realistic bodies and faces in games such as Beyond: Two Souls and Until Dawn. It doesn’t do the motion-capture itself, but it takes the data and, using a big team of technicians in the Philippines, cleans it up so that it can used state-of-the-art video games. This behind-the-scenes tech is one of the engines behind modern video games, and it is only beginning to become a more diverse environment.

Rausch has been in the business for 15 years, and she is sometimes still greeted by strangers as if she were a marketing person, not the CEO of her company. She believes she is doing her part in making the industry more hospitable for women. But she is not one of the well-known women in the game business.

On the one hand, her technology enables game makers to create female game characters who are larger than life, as well as faithfully realistic in comparison to the way that humans actually look and move. I interviewed her recently about her role in gaming. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

GamesBeat: Can you start by talking about how you got into the industry?

Marla Rausch: When I started, the industry wasn’t a place where there were a ton of schools out there teaching 3D animation. It was a very new thing. It tied into motion capture. Everyone learned by being involved and being a part of it.

My husband was a part of it, which is why I got involved. He was setting up a studio in the Philippines, and then he went to the U.S. and set up a studio. He was doing motion capture work. I was about six or seven months pregnant, waiting for him to leave, and as I sat there waiting I leaned over and said, “What are you doing, anyway?” That’s where it began from me. He taught me how.

I started doing freelance work for Spectrum Studios and Sony when they needed freelancers during crunch time. I’d work on my full time job and then go over there to work.

GamesBeat: Which part of the business was that?

Rausch: I was doing motion capture cleanup work, which is tracking and making sure that the data captured on stage is going to be workable, that it looks good, that it can go to the animators without any problems. The biggest issue in motion capture is, for the longest time, people would say, “Oh, this is cheaper and easier. You can do walk cycles much faster than on a key frame.” But people need to understand that it’s only faster and easier if you do it right the first time. That’s where things sometimes go off track.

Say the stage itself isn’t calibrated well. Something shook the stage and all of a sudden the data isn’t clean enough. People let that go. Then you’d have people like me saying, “Why on earth is he just standing there with everything blinking on and off?” That just goes on down the line. If I have trouble with it, the animator’s going to have trouble with it, and ultimately it just gets to be a bigger and bigger problem as it goes through the pipeline. I started working in 2000 or 2001, somewhere in there.

GamesBeat: What was the quality of motion capture at that time? Was it used for the whole body or just certain parts?

Rausch: When we started doing motion capture, it was interesting, because I saw the development of the technology, both hardware and software. The markers got smaller and smaller as the years went by. The cameras themselves were able to pick up the reflections more clearly.

It used to be that if you had two or three people in a volume, you were pushing the data quality. You’d sometimes have a harder time getting all the data in the machine. The occlusion level was quite high. Nowadays, two or three people on a stage is as easy as one person on the stage back then. It’s relatively easy.

Using optical data, optical systems, anything that’s occluded is going to be a problem. If you have two people rolling around on the ground, then or now, you’ll still have trouble making sure you get all the motion in your scene. But nowadays we’ve worked with as many as 19 people inside the volume, and we got good quality from all of them. We got very little occlusion, because the hardware is able to handle it.

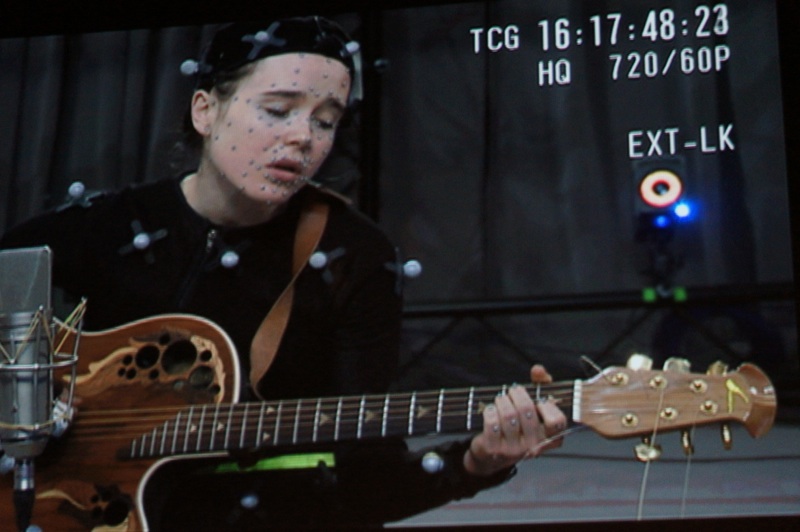

Years ago it was mostly just capturing the body. Facial capture wasn’t where it is today. You’re talking about tiny markers on the face and trying to get a camera to identify them without making them turn into one gigantic blob. These days, body cleanup for motion capture — there’s an acceptable standard. We know exactly what goes into it. We know when it’s good enough. We know when there’s nothing more you can do. But we’re not quite there yet with the face.

With the face we’re still finding out what pipelines and systems would be best utilized, especially with the games coming out now. You have things like Heavy Rain or Beyond, where it’s about facial expressions and the emotions on each character’s face that creates the impact on the audience. Today we’re doing with the face what we were doing with the body a decade ago, figuring out the best practices, the ways we can cut costs, the ways we can exceed quality expectations, and the ways we can shorten the amount of time it takes so we can release our games on time.

GamesBeat: Were you a serious gamer at the time?

Rausch: I embarrass myself when my husband and I talk about this. Back then, the game I played was Rollercoaster Tycoon. I was about two weeks into that game. I was getting really good at improving parks and having enough people in there to meet goals. After two weeks, I realized, “I’ll never get that time back, and I didn’t actually build a roller coaster.” Then I thought maybe I should focus on my work more. But I do enjoy games. It’s one of the ways I relax.

GamesBeat: You didn’t need mocap for that game.

Rausch: Nope, it did not. But at the time, too, when you’re talking about mocap, you’re talking about war games and wrestling and stuff like that. These are games I liked to watch, but I was never very good at them. I react the way I would in real life — run away when there’s somebody shooting, that kind of thing.

GamesBeat: It sounds like a pretty technical job. Was it mostly technical work, or would you say that it wasn’t something you needed a lot of technical training to learn?

Rausch: It is pretty technical. When Animation Vertigo started and we were looking for people to work for us, we needed to make sure they were technical people. People who weren’t necessarily looking to be creative or artistic in their work.

More often than not, what you’re dealing with is dots on the screen an

d making sure you can recognize what those dots make. You need to make sure the entire scene is taken in. You see the two actors talking or running or shooting each other, and you should be able to make sure that comes out. There’s very little artistic or creative eye needed there. You just need to make sure it’s faithful to what was captured on stage, what the director wanted.

We’ve progressed, though. When Animation Vertigo started we were working on motion capture cleanup, getting the data from the stage and cleaning up the occluded data. About seven years ago, we started moving into what you call retargeting. In motion capture, once you have all your data cleaned up, the data from the markers goes to an actor, which now has the rotational information. You start with translation and you go to rotation, which means the data goes into a standard gray actor of whatever size. From that size, then you put it into a character. That process is called retargeting.

I try to explain this to my mom sometimes, because it helps me to explain it in a way that’s more interesting and easier to understand. Basically, there isn’t going to be an oversized human out there. But say we have to capture a human – hopefully bigger, taller, more muscular — and then turn that regular-sized human into a seven- or eight-foot ogre. You’re going to see that the motions of the regular person don’t quite match what the big ogre would do. Or the other way around. A regular-sized human doesn’t match the movements of a dwarf.

When you do retargeting, you’re trying to make sure that the motion captured on stage is correctly interpreted into the character. At that point, you want to have people with an artistic eye, with an eye for animation. You want to see an ogre that walks and moves naturally, not stiff or robotically. You can tell when the animation isn’t working when you look at the gray version. You can’t quite put a finger on it, but there’s something wrong with how it moves. So while we started with purely technical work initially, we’ve moved on to work that needs a technical person with that artistic eye, someone who can tell when the movement looks natural.

GamesBeat: What was it like being a woman in this part of the business? Were you the only one, or were there others?

Rausch: It’s a tough one. When I first started, there weren’t a lot of women in that side, in the technical side, or in the decision-making side. Most of the people I interacted with, who made decisions on the teams, were men. I’ve been fortunate to have a very good experience. There’s been a lot said in the media about how the industry has been hard for a lot of women, but I’ve been fortunate to deal with people who understand that not only is this a fun industry, it’s a serious business.

It’s unfortunately common that when I do meet someone for the first time, their initial expectation or thought process is that I’m doing sales or marketing for Animation Vertigo. But we’ve moved into a different place these days. More women are executives, people making direct decisions. That hasn’t quite reached motion capture yet, though.

A story I tell people is that during the 10th anniversary party for Animation Vertigo — we decided to throw a celebration during GDC. We invited clients, folks we knew in the industry who’d worked with us, software people, hardware people, basically everyone who had a hand in helping Animation Vertigo be the company it is today. As we were taking down the guest list, my assistant looked at me and said, “Um, are we inviting any women?” That struck me. It didn’t occur to me that everybody we’d directly worked with were all men.

GamesBeat: Is this something you’ve tried to work against, finding a more diverse group of people for you to work with?

Rausch: I’m doing my part. I’ve been involved in mentoring and UC Irvine for women in computer science and computer gaming, working with girls in middle school and high school. It’s one way I’m able to bring women into the industry at a young age.

It’s an experience I’ve had personally with my daughter, when she was a sixth-grader. She’s sitting in front of a computer, holding her iPad, and she says, “I’m just not good at technology.” And I look at her and say, “You’re working at a computer and you’ve got an iPad. I’m not sure just what technology you’re talking about.”

I realized that’s where it begins. They’re surrounded by boys who play games and love games and maybe even program or make games. At some point or another girls decide, well, that means they’re better and we’re not. Most games are aimed at boys anyway, and so they lose interest. My way of giving back is mentoring, working with women who want to be in the industry, who have a lot of questions and insecurities about what the industry is like. They’ve heard all about Gamergate and all these horror stories, but what’s it really like?