As Niles Lichtenstein thumbed through old albums, he fell into that rabbit hole we all fall into when ridding closets of abandoned sweaters and unused tennis rackets. How quickly a cleaning project turns into a trip down memory lane. Soon Lichtenstein was playing record after record, reminiscing about the tunes he and his father would sing along to in the car.

His father died when he was 12 years old, and Lichtenstein never felt that he had an opportunity to really get to know him. But listening to the quiet melody of an old Eagles album, he hungered to find out more. Albums gave way to photographs and soon a full search into his father’s time in Vietnam during the war.

As Lichtenstein was piecing together his father’s biography, he realized there was no way for him to share all the various photos and anecdotes he had gathered. Ancestry.com, though a good resource for genealogy, didn’t allow him to post all the multimedia he had accrued, and Facebook wasn’t the right venue either. Even more important, because of the intimate nature of the story he had to tell, he didn’t want to post it on a social network that anyone could see.

“I’m [not going to] post the poem that got me through that depressing time on Facebook,” Lichtenstein said, by way of example. Instead he decided to build his own platform where people could create amalgamations of text, video, audio, and artifact woven together to form a shareable record. To scale it, he joined Matter Venture Capital’s incubator, where he coaxed his vision into existence over the course of 20 weeks.

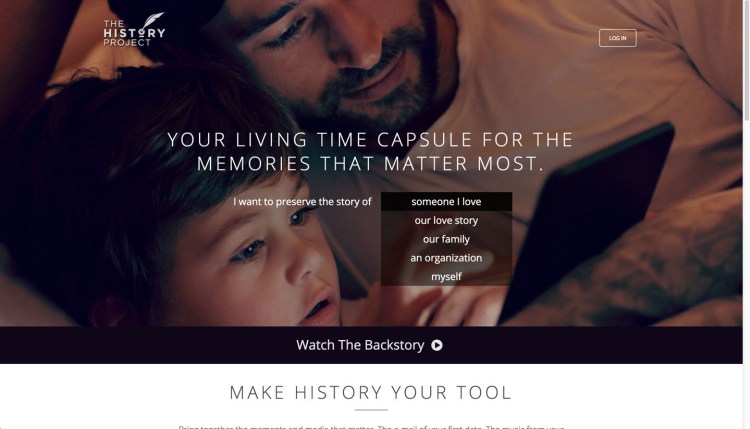

The result is a platform for building embeddable multimedia timelines, called The History Project. The site lets users create their own timelines to be shared publicly, with a small group, or not at all. The platform integrates with YouTube and Vevo, so a person can plant relevant songs in their timeline. For now, there are only two other integrations, one with the Associated Press, for adding news stories, and one with Billboard, for linking music charts. The History Project also allows users to import their own photos and record audio clips, so people can recount their memories, the way they might to a friend.

Now, for the first time since its inception, the platform is emerging from beta and launching to the general public.

It’s a strange yet compelling project. Though time capsules aren’t a new concept, The History Project feels like the next generation of social media: a place where people can chronicle their experiences from childhood to retirement without ever jotting down a word. It’s also the stuff of dreams for media outlets trying to expand beyond written articles.

No surprise then, that the New York Times was the lead investor in The History Project’s first round of funding. Since joining Matter’s incubator, the company has raised $2.1 million in combined angel and investor funding. Funding may only be the beginning of The History Project’s relationship with the Times, however. Eventually, the two might collaborate, bringing archival Times news clips to The History Project’s timelines.

The Times isn’t the only media property to notice The History Project. HBO worked with the startup to build an interactive timeline accompaniment to its new documentary, The Diplomat, about U.S. foreign diplomat Richard Holbrooke.

“Together, we have built a personal, in-depth and interactive timeline of Richard Holbrooke’s life and achievements that can be used as a companion piece to the film debuting Monday night on HBO at 8pm EST,” reads a post on the film’s Facebook page. HBO boasts that the timeline contains exclusive photos and memories, giving viewers a behind-the-scenes look at Holbrooke’s life.

In addition to serving as yet another place where people can cobble together a glossy personal image of their life, The History Project also provides a space for biographies and the retelling of historical events. That is to say that through The History Project, a multitude of people can create their own version of a historical event. Or, alternatively, an unlimited number of people could contribute to a single timeline, begetting crowdsourced histories.

What is most compelling about the project is its potential for expansion through integration with various archives, social media networks, and other large databases. Furthermore, it could accomplish something that Facebook has tried and failed to do. Facebook has become a repository for real-life moments captured on film and in text, but it’s not an easy timeline to traverse. While the company has created some tools to reinforce the idea of Facebook as a digital scrapbook (through better search features and videos that pull together your earliest and most popular posts), it’s still not a flexible tool for recording a lifetime’s worth of experiences.

The History Project is no Facebook, but it stands to give people a tool to comfortably share personal details about their lives and the lives of people close to them.

As we wrapped up our conversation about the project, Lichtenstein divulged that a friend of his dad’s from the Navy told him his dad was quite the partyer. Lichtenstein said he wasn’t familiar with this side of his dad, until he stumbled on some old photos.

“There’s this picture of him wearing a dress in Dolores Park…” Lichtenstein said, trailing off as his laughter took hold on the other end of the line. It’s the sort of image that you might want to share with family and friends, but maybe not with the world.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More