SAN DIEGO — The big question among tech investors and entrepreneurs today has to do with how quickly a new computing paradigm will arrive. Augmented reality and virtual reality are expected to be huge markets, but when will they become huge markets? The first major VR headsets from HTC and Oculus VR are expected to launch early next year. But will that immediately lead to revenues and opportunities for app makers and startups?

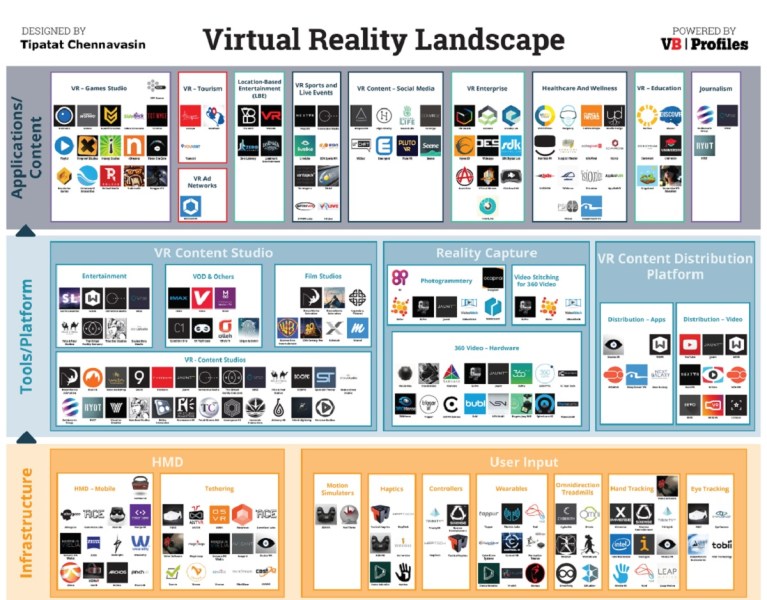

AR and VR are expected to become a $150 billion industry by 2020, according to Digi-Capital. There are more than 200 companies chasing the VR market and raising money to be ready for that market. I moderated a session last week on the prospects for AR and VR at the Intel Capital Global Summit in San Diego, California. We focused on the outlook for investment, the acceleration of the technology, and our predictions about the future.

The panelists included Ron Azuma, a seasoned AR/VR researcher at Intel; Dan Eisenhardt, CEO of the Intel-owned Recon Instruments augmented reality glasses provider; Ray Davis, Seattle studio manager at game developer and game engine maker Epic Games; and Andrew Beall, CEO of enterprise VR company WorldViz. They had expertise that ranged from gaming to enterprise VR, and had some deep experiences going back a long time.

Here’s an edited transcript of our panel.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

GamesBeat: Market researcher Digi-Capital estimates that virtual reality is going to be a $30 billion market by 2020. Augmented reality will be a $120 billion market by that time. Our own VB Profiles estimates that right now there are 234 startups that have raised $3.8 billion to date in virtual reality alone. They’ve created a collective enterprise value of around $13 billion and they employ about 40,000 people. Pretty good for an industry that has no sales yet.

We have a great panel to discuss these things, and now I’ll have them introduce themselves.

Andy Beall: I represent a company called WorldViz. We’re unique in a couple of regards. We’re one of the original VR companies. We’ve been in business since 2002 providing VR services and a universal development platform for professionals and enterprises to get into virtual reality and build content that has productive reality to it. We also have our own tracking system. My firm belief is that one of the most provocative ways to get into VR is to walk through it. We have an illustration up where you can experience our wide-area walking system in 1:1 scale.

My personal involvement with virtual reality dates back a decade prior to 2002. I come from a scientific background, using this technology to study human performance. The roots of my interest are in using this technology to understand the human condition, and that’s then fed into industrial applications.

Ray Davis: I’m a game developer and have been for about 15 years now. VR and AR are fantastic. They open a whole new frontier for us as far as attacking the experiences we can build. That’s exciting for us on the creative side. At Epic Games we make the Unreal Engine in addition to building our own games. We’re jumping into VR development so we can make sure we’re building the features and technology that can make VR available to everyone. They can take advantage of this platform and realize their visions.

In my personal career, I was working on the HoloLens project for about three years. I’ve had a good bit of experience with VR, AR, and combinations thereof. I’m a firm believer.

Dan Eisenhardt: I’m the founder and now CEO of Recon Investments. We were acquired by Intel this year. Our story dates back to 2008. The idea came out of swimming. I used to be a competitive swimmer, and I always wanted to have access to data in the pool. We ended up launching our product this month. It’s big with snowboarding as well. These people love technology, and they’ve found a way to do a lot of things on a mountain which a lot of technology usually can’t do for you. There was a real pain point we could solve, and that’s been the foundation of our products. We always look at solving problems. We’re not really in AR or VR. We’ve just been interested in solving a problem, and AR is what we used to deliver the solution.

Ronald Azuma: I work at Intel Labs. I’ve spent my entire career in industrial research. I come from more of a research and academic background than a business background. I first started working on virtual reality back in the late 1980s as a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill, but I’m mostly known for augmented reality. I wrote an early paper that defined the field and guided a lot of early work in the area. I have over 25 years of experience in this area. I’ve been able to see the technical and spiritual developments, as well as what still needs to be done.

GamesBeat: What still needs to be done? We’re in a bit of a frenzy that started a couple of years ago. It surprises me how much momentum has grown behind VR this time around. There was a VR meetup that formed in May of 2014, right around when Facebook bought Oculus. It started with 60 people in Silicon Valley, and it became a whole conference unto itself this fall. Developers are going to these things and consuming every piece of information they can get about VR. I wonder how you can add some perspective to this. Are you surprised? Have you seen this before? Is there a good reason for all of this to be happening at such an accelerated pace?

Davis: Anybody who’s ever experienced a compelling VR experience can tell you. “Why is this happening? Because it’s amazing.” This is going to redefine how we interact with technology and computers over the next decade and beyond.

Over the next year, especially, this is going to be a critical year for VR. Oculus, HTC Valve, lots of these manufacturers will be bringing headsets out there. We’re going from a small tool that 100 or 200 developers can access to potentially thousands or tens of thousands. Then you’ll see a massive wave of creativity and expansion of what’s possible on the platform.

I see a lot of similarities to what happened with mobile phones. When Apple introduced us to the iPhone and the App Store — “Hey, look at this touch thing” — it started with fart apps. But eventually it led to some really compelling experiences that didn’t make sense on a PC or laptop or any other form of computing. Where we’re going with VR and AR is just a natural evolution.

Beall: VR has undergone a drastic revolution in the last couple of years, largely because of Oculus, but we’ve had other major players come in. The changes that have been very relevant are about comfort, allowing people to spend much longer in VR at any one time. Ease of use, performance for low latency. People aren’t getting sick. And finally price is the promise we’re all looking to see fulfilled.

Davis: How much do you think consumer VR is going to cost this year? That’s still the question.

Beall: A lot. Compared to five years ago, though — commercial VR cost thousands of dollars. Just out of curiosity, how many people here have had a compelling experience of VR? About half. Compelling to me would be something that’s very provocative, like walking the plank.

Azuma: I was one of the people originally working at UNC who did that. In the very early days it was almost like a religious conversation. Did you feel a presence? Did you feel that you were actually immersed inside this environment? Some people argued that yes, they did. Others didn’t. My partner, Gary Bishop, argued that he’d never been present inside virtual reality.

We had a virtual model of a kitchen, and we had a macro tracking system. We asked people to kind of squat down and look at the height of the tables and cabinets there. Gary walked in and was immersed in this. Another person and I watched this. When we told him it was time to get up, he did this. Of course, there was nothing really there, but at least for a millisecond he was fooled. He was actually present.

The end result, though, is the question of how you actually measure whether somebody’s present in that. Well, you still don’t.

Davis: This is where I have to register a formal complaint. Why are you trying to make people scared?

Azuma: It was to try to get objective measures of presence. This was the core of the experience….

Davis: Research is great and all, but what I worry about is that I’m going to pay a lot of money for this thing that freaks the hell out of me. There are magical things you can do with VR. It can take you anywhere, any time.

Beall: And so from a marketing point of view, if you’re trying to make VR commercially viable, it’s one of the fastest ways for somebody who’s never tried this to walk in off the street, and after about 10 seconds you no longer have any doubt that VR is real.

Davis: Here’s my favorite followup question. How many people here have tried 3D TVs and said, “Yeah, whatever”? 80 percent, I’ll call that. Anybody who’s tried VR doesn’t raise their hand in that same situation. Once you have that experience you get it. This is something far more compelling. It’s amazing.

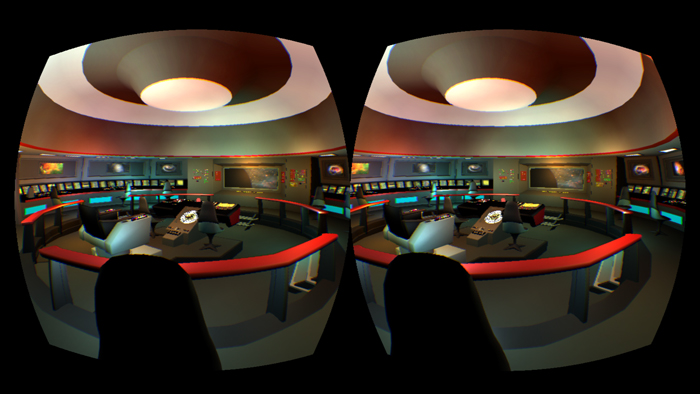

Our team just put together this demo where we’re playing with the touch controllers from Oculus. Initially in VR you obviously notice presence. Everyone talks about presence and immersiveness. But there’s another level of hand presence, when I have hands. We built this little shooting mechanic thing in, but 90 percent of the time, when people get in there they’re just amazed that they have hands. It’s the most natural thing. In reality I don’t pay much attention to my hands, but if it’s virtual reality, it’s fascinating. It’s a whole new level.

GamesBeat: One good question to follow up on — maybe the audience gets presence, but what are you going to do with it? How long an experience are you going to create? Are you going to make this a 20-hour video game? Or is it like a horror movie, where once you pull the jump scare on them they’re not going to get scared anymore, so you have to fool them with something else? What’s a good example of something you can only do in VR with that sense of presence?

Beall: To me, presence is one of the products of the technology. I liken it to a hallucination. It’s powerful. It’s provocative. It’s overwhelming. It’s convincing. But hallucinations by themselves aren’t necessarily a good thing. They aren’t the goal. It’s the story you tell with that hallucination, the meaning behind it, that adds the value to VR.

Again, we’re not just in the business of scaring people, but imagine safety training. If I can provoke in you a sense of bodily harm, do you think you’re going to pay a little more attention to the golden-rule pamphlet that I’m trying to get you to sign off on? You bet. Same with evaluating a critical design review. If you’re about to build a hospital and make a half-billion-dollar investment in operating rooms, would you want your stakeholders to feel completely committed?

Eisenhardt: The practical applications of presence are amazing, especially in something like architecture. I can make a perfectly to-scale environment on a screen, but I don’t really get a sense of that space and height of the ceilings until I’m there in VR. It’s terrible to try to describe it, but there is a difference between a 2D presentation and being there in that environment.

Azuma: Both AR and VR have potential as new forms of media. People ask what’s the critical aspect of these that’s different from TV shows and video games and other kinds of things, and it’s presence. It’s the belief that I am actually in that apartment. I can move around. I can choose what I do and it reacts to that.

GamesBeat: Dan, let’s bring augmented reality into this a little bit too. You don’t have presence with augmented reality glasses. It’s not immersive. Why would we want to do it?

Eisenhardt: Because I spend most of my time in the real world. When you live in the real world and work in the real world, sometimes instead of being immersed in a completely different environment — whether it’s for entertainment or training or other things — you want to live your day to day life. You want to be able to see the world and understand things in it. That’s why I think some people project, as you said, that ultimately the market for AR will be larger than the market for VR in the long term.

Losing situational awareness is a big thing for people. They might love the Oculus Rift, but they would never wear something like that on the plane or in public. There’s this notion that you’re isolated, that you lose a bit of your humanity. That’s a challenge. But in enterprise, the opportunity is so huge, for training and all kinds of other things.

I’m wondering, what are the challenges in VR? Is it price point? Is it a mature ecosystem for the software? What is it, actually? It seems like the opportunity is so huge that it should outweigh any of this.

Azuma: One of the most serious is vection. The systems that are going to be available in 2016 — I’ve been very impressed by the technology. I assume the price points are going to be accessible to consumers. If you’re in a situation like those of us up here — you’re sitting in a chair and you’re only moving your head a bit and looking around. I’m not going to be able to get up and walk in a room in a space like this. Vection describes the sensation of flying or moving around in a first-person shooter game, even though I’m actually sitting still. It’s a conflict between what the inner ear is saying and what I’m seeing. That’s a very serious problem.

GamesBeat: You don’t want your customers throwing up, right?

Azuma: One approach to try to deal with this is using electromagnetic fields to induce a sensation in your inner ear and try to match what’s happening visually. My response to that is, “You go first.” Omni-treadmills are trying to provide the sensation of walking, but all the treadmills — it’s not the same as actually walking yourself.

Beall: We may need to frame this problem a bit, because I’m not sure everybody has experienced enough VR to know. One of the holy grails is being able to experience and navigate large spaces. Those of you who’ve tried Oculus, the experience may have been seated. You’re allowed to look around, maybe move your head a little bit, but that’s far different from, say, walking around this room. Or using some sort of controller to just blast through the wall as if you’re Superman.

Obviously serious impact is a problem. Ron’s looking at the fact that if you allow full control, you have serious motion sickness flaws. There are a few techniques, one of which we use. You get away from the fixed stool and get on a pivot stool. Don’t ever let a virtual person rotate with the joystick. Have them pivot with the stool and you avoid some of the inner ear conflicts. But as you see, we’re clearly dealing with some subtle human performance and perception problems.

GamesBeat: Then you also start tripping and bumping into your furniture.

Davis: Yeah. There’s the chaperone problem. We ran into this with Kinect. People didn’t want to move the coffee table, and then they complained when they kicked their coffee table. The interesting thing, though, that we’re learning from a lot of VR and AR developers, is that you acclimate to a lot of the physiological impacts and dissonance.

Some of our core developers say, “I don’t trust you when you say that this won’t make anyone sick. Let me get our person who always gets sick.” Because there is an acclimation that starts to happen. Another thing is, how much of this problem is for us to solve now in this generation, as opposed to in the future when people take these things for granted? It’s going to feel a little funky at first, but the tradeoff in the form of the experience you get more than outweighs the cost.

GamesBeat: Is processing power going to solve this problem?

Azuma: Is processing power going to solve motion sickness? We’re talking about physiological problems.

GamesBeat: But if you can refresh fast enough….

Azuma: You can do better tracking. You can do lower persistence and other types of things that have licked it when you’re just sitting and rotating in space.

Beall: To the point about adaptation — we’re on an interesting trajectory. We’re on the precipice as far as many aspects of VR being viable as a large-scale option. That said, there is a rich history, 10 and 20 years, of putting up with artifacts. I’m not saying we should, but there are cases in which there’s enough return on that investment, enough productivity to be gained. There are cases where we need to have some compromise in order to gain what we can today. We can’t expect this to be absolutely perfect.

Davis: We’ve found that if you maintain a consistent frame rate, 90Hz being the holy grail for VR right now, and you avoid things like — don’t dramatically change the environment in a single frame. Otherwise, the brain is really good at adapting to these things. We’re constantly trying to reconstruct reality from poor sets of data. This is just an extension of that.

Eisenhardt: You asked about what some of the challenges might be. One thing that’s worrying on the business side, the application side, is that we have to field test equipment with a given experience. It doesn’t mean that every application that is developed may follow those kinds of guidelines. I don’t know how the companies prevent that from happening. Then the consumer will be in a bind of having spent a lot of money on this, they go through a few of these things, they don’t like the reaction, and then what?

Davis: You’re right. As a developer that’s one of our main fears. You look at the Oculus and Valve HTC devices right now, they require a PC. The PC represents a lot of variables — what drive you have, what CPU you have, what GPU you have. Even if the developer does their best, the consumer might still have a terrible experience.

This isn’t some random application crashing on your computer. That sucks, but you just reinstall it or whatever. If a VR application has a terrible performance or crashes, that’s going to have physical effects on you. You’re gonna say, “Yeah, no more VR for me. I’m done.” The stakes are that much higher for people. I don’t know that every developer has totally bought that yet. They don’t understand yet. We all need to hold ourselves to that high bar. Otherwise we’re gonna make people vomit.

GamesBeat: There’s another high bar in AR as well, Dan. Magic Leap, which drew the half-billion-dollar-plus investment from Google, and some other folks, their stated goal is to create augmented reality images you can see through your glasses that are indistinguishable from real life. Think Jurassic World. You’re walking around a park seeing dinosaurs, and they’re fake, but you can’t tell. Are we going to get there? Do we have to get there?

Eisenhardt: That was going to be my comment — do we have to get there? We have to solve problems, good problems. They can’t just be gadgets. That’s what we’ve been focusing on at Recon and now at Intel. We’re solving problems and becoming essential.

VR is essential, or it should be essential. For AR, at least in the space that I’m interested in, it’s mostly outside. We’re wearing something on our faces and then through that we have access to information that’s more convenient than our traditional interfaces.

What’s happening as far as macro trends, we’re always checking our phones a hundred times a day — text messages, emails, everything else. Fast forward five years, when we have 50-billion-plus devices – your refrigerator generating data, your dog’s collar generating data — you’ll be more and more bound to your phone all day. That’s the thing about the humanity aspect I’ve brought up. You lose touch with humanity.

So how do we solve that problem? The solution is different depending on the situation. We’ve gone through the vertical. We’re going to create products that solve real problems right now. When we’ve done that, we’ll go on and build the next one. Eventually we’ll get to a space where everyone will be buying and wearing these devices.

Azuma: It’s a great visual that you bring up, Dean, but I don’t think the field has to get to that in order for AR to be useful. Think of the yellow first-down line when you’re going to see a football game. That’s an augmentation in real time. Is it useful? Sure, in terms of understanding the game. That doesn’t mean you mistake that for reality or that it has to be indistinguishable from reality in order to be useful. If I’m walking around Seoul and I can’t read Hangul, if have an app that translates signs into something I can read, that may not strain the muscles as far as displaying the text, but it’s still useful.

Davis: One of the things I’ve round really impactful in augmented reality app development — right now, with my smartphone, I have a hundred apps or so and they’re always with me, all the time. In order to find one I have to browse through all the hundred of them. But in augmented reality, you have a notion of space. You can start to map that out in relation to what’s in my phone.

If you use a recipe app, you generally have that open in your kitchen or at the grocery store. You can match that with a computer’s understanding of location — oh, we’re in the kitchen now, let me make sure that app is accessible. It’s there before I even knew to activate it.

You mentioned something that triggered a thought for me. The internet of things is ridiculous. We’re going to be just overwhelmed by too much data all the time. The idea of machines starting to get that understanding of our environment and our life, being able to position these things through AR experiences — that sounds fantastic.

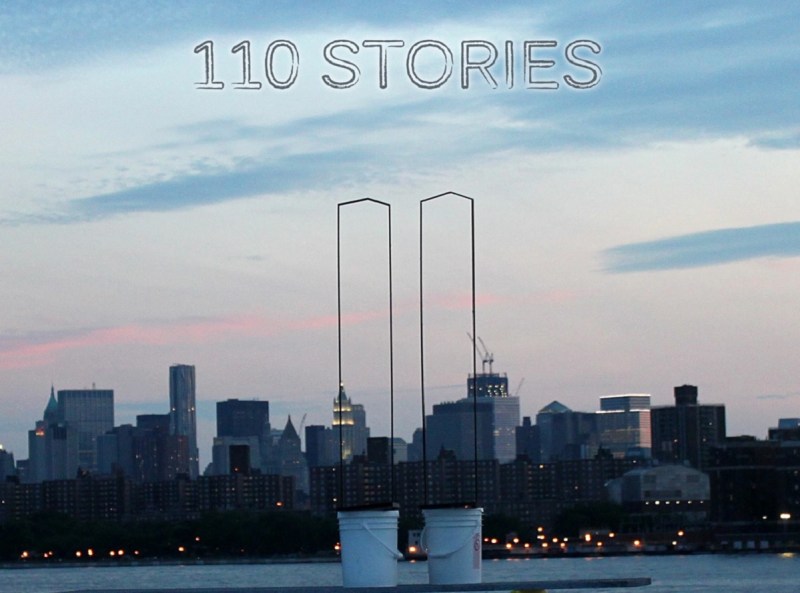

Above: 110 Stories is an AR iPhone app that lets you see where the twin towers would be.

Azuma: Think of a parallel digital world that’s going to be tracked by Internet of Things devices. How are we as human beings going to interface with that and understand that within our environment? AR might be the interface we use to solve that problem.

Here’s another example to the question of whether it has to be truly photorealistic. One of the most compelling experiences I’ve ever seen is something called 110 stories. This was an app on an iPhone that would, if you pointed it at the New York skyline, would measure an outline of where the World Trade Center should have been.

To me, there were two design decisions that made this particularly compelling. One is that even though we have the graphics power to render something that looks real, the designer chose not to do that. Instead, he added just an outline of the towers, as if they were sketched in against the sky with a grease pencil. To me that made it much more compelling, because it played into the message it was trying to convey. They’re not really there.

The second aspect was, you could take a picture and then it invited you to write a few sentences. Why did you take this picture? What does it mean to you? If you go to the website and read some of the stories — as you might expect, some of them were very emotional. For me, the power of augmented reality — for VR it’s presence. For AR is about making a meaningful connection between reality and something virtual, the combination of the two. It’s a different type of experience from an untouched reality or an entirely virtual one.

Davis: One of the things I see as a game developer — games are about empowerment. The most amazing games out there make you feel like a superhero or a wizard or whatever your fantasy might be. Augmented reality is going to play a part in that, especially combined with the internet of things. I have all kinds of things I can control with technology now. A virtual experience can start to invade reality in a way that nobody else could ever do before. That opens up all kinds of new horizons.

My favorite thought experiment about this is, hey, I’m going into Starbucks. I love going to Starbucks. It’s my favorite coffee shop. Imagine if no matter what coffee shop I go into, my augmented reality glasses can remap it, and I have my Starbucks experience.

GamesBeat: I want to take this back in a certain direction here. For investments, what still has to be invented, from your point of view? What would be worth some of these people looking into and putting their money into? What are the unsolved problems, the things that have to get done?

Davis: What’s obvious is that there’s no market yet. People don’t own these devices. We don’t know what the killer apps are. There are no defined business models. What does it mean to sell a VR app? Is it a free-to-play type thing? Do you pay as you go?

GamesBeat: We have them in a market, but we’ve shown up only with headsets. We’re still missing a lot of stuff, like 3D audio or wireless headsets. What do you do with your hands and legs?

Beall: From my perspective, working in the enterprise world, it’s content. Getting content into the system. The fidelity of displays and the compute power have reached a point where there’s a lot of viable applications, but getting real content — either through reality capture, where there are some very interesting applications happening, or getting digital assets — we deal with no customer anymore who isn’t already invested heavily in their IP as a digital asset, whether it’s a construction firm, manufacturing, or even training. Yet there’s very little workflow to convert that into realtime graphics. There’s a huge investment to be made there.

The management of those resources for streaming is another area that’s just on the brink. Speaking to the subject of human motion capture, we’re still fairly crude when it comes to being able to fully capture my body and my hand motions. The more we do there, the more fluid that becomes, the more comprehensive this technology becomes as far as allowing us to function.

Azuma: There are much deeper issues in terms of trying to perfect these experiences. We’ve said that presence that’s palpable is the thing that differentiates the medium. A lot of people are trying to do 360 camera views for VR. That’s a step. That’s sort of like the early days of TV, when people recorded plays. It wasn’t taking advantage of what the medium of TV could do that was different. It was using a traditional stage and things like that. What’s the answer to that with VR? That’s the question that the field needs to struggle with.

GamesBeat: For AR you have to get all this data from the cloud into your glasses. How is that going to happen?

Eisenhardt: We have killer apps. I think we have killer apps for the verticals that we’ve targeted. The real hurdle, I think, is getting people to actually wear these things. Getting your hardware to a stage where it’s completely seamless — that involves tight collaboration with the fashion industry moving forward. We’ve been doing that for years. That needs to continually accelerate. And the tech life cycle versus the fashion life cycle — they couldn’t be more different, on all tiers. That’s a challenge. But the form factor, the industrial design, all that stuff — if you can’t solve that and make these things look great, people won’t wear them.

90 percent of people who go skiing wear goggles already, so we can go in and work with them. That’s why we started there. But if you’re talking about walking around, inside or outside, right now, it’s a sacrifice for us. We’re forced to change our behavior. That’s what I’m talking about now. At what point do people say, “Okay, I’m in”? Once they buy in and put on these glasses, they’ll realize it. “I have all this information that I didn’t have before.”

Davis: You guys were absolutely smart to start with the snow goggles, because there’s already a crazy form factor that allows you to do some cool stuff. We’ve seen revolutionary technologies in our lifetimes, right? The internet, the smartphone. We already spend more time with our smartphones than we do with our significant others these days. Why is that? It’s because the value of this device, of the internet and media and all these other things, is so significant. We need to overcome the same barrier, the same hurdle, with AR and VR.

GamesBeat: These are all very intimidating things. But what’s interesting to me is the speed at which things are improving and how fast we’re learning. I’ve watched the Epic VR demos over a few years now, and they’re getting better and better. The last one you put together was 12 people, right? Maybe the next one will take 30 people working for a year. But eventually you’re going to learn so much doing that, you’ll either have an advantage on everyone else when the market arrives. That’s the theory, right?

Davis: Obviously getting involved early with the opportunity is advantageous. Personally, what I look at is — VR, for someone like myself, is easy. I love new frontiers. I want to believe. But what does it take for my parents or my friends that aren’t in the tech space to want to go buy this device? What does that involve? I haven’t seen that, personally. I would love to hear that idea. We can talk about wires and batteries, but it’s really that experience, that content, that we’re missing so far.

Azuma: We need the Eisensteins and the Buster Keatons, which we haven’t had yet.

GamesBeat: Investors are looking at this and saying, “Okay, we have to cycle through a lot of experiments and failures and things that aren’t going to work for years? We’re going to fund these things in the hope that this will all come together?”

Davis: As a software developer, I say you should invest in software developers. But seriously, to go back to an earlier statement, this year is the most pivotal. Hardware has been really hard to get your hands on. So many people out there have fantastic, creative ideas — people from the games industry, the film industry, all kinds of interesting verticals — and they’re converging on VR. Those are the people you want to bet on.

Who knows what the experience is going to be? I’d feel pretty arrogant saying, “It’s going to be social communication gaming!” or whatever. Nobody knows yet.

Beall: We’re seeing huge uptake in Los Angeles, in digital Hollywood. Movie studios are seeing this as a major play. I was there a couple of weeks ago and there’s a whole different vibe, a whole different conversation down there. Huge investments are going on. That’s going to lead to all sorts of investment opportunities in content distribution.

As an aside, talking about augmented reality, I don’t know if you consider this Apple Watch an augmented reality device, but it has haptics. That’s the most ground-breaking thing there. Something that’s an area for investment is other modalities. We think of VR as being visual reality, but it’s really virtual reality, across any modality. That’s the challenge. Traditionally, the senses other than vision have been much more difficult to attack. Augmentation through acoustics, augmentation through haptic devices, that is all ripe, ripe territory for all sorts of development.

Eisenhardt: For investors to flock to the space there needs to be the feeling that this is really going to happen. This is going to blow up in the next five years. If you’re looking at something more like 10 years plus, they may as well be sitting on the sidelines. But we’re already seeing investments happen, in both AR and VR. A number of companies are just on the cusp of coming out. In the next two to three years, I think, we’ll see AR start to take off.

Audience question: Will games or porn take off?

Davis: Let me answer a different question. There’s a trap in VR and AR as well, which is the tendency to think about one specific set of applications. It’s not that. It’s not about games. It’s not about any of these things. It is about the future of computing. When we extrapolate and solve all these hardware problems, when we have screens embedded in our eyes or wherever the hell we want them, I don’t need computers or mobile phones or watches anymore. It’s a danger to look at this as a binary situation.

Azuma: It reminds me that once VR gets better than dating, then the human race will become extinct. I used to get his question when I was a grad student all of the time. I’m working on all of these important applications and that is the first question you ask me? The real answer? Tell me a form of communication or medium that hasn’t involved that. It’s different forms of media that will cover everything. We won’t have just one particular genre like VR horror.

GamesBeat: OK, Intel endorses porn. You guys heard it here.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More