Want smarter insights in your inbox? Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get only what matters to enterprise AI, data, and security leaders. Subscribe Now

Morgan Stanley. Anthem. GitHub. Ashley Madison. WhatsApp. Experian. The Office of Personnel Management. Dow Jones.

All of these organizations revealed hacking incidents in 2015. There have been so many that Dow Jones chief executive William Lewis remarked that “no company is immune” to an attack.

All of these organizations revealed hacking incidents in 2015. There have been so many that Dow Jones chief executive William Lewis remarked that “no company is immune” to an attack.

Companies trying to figure out how to defend themselves against hackers are looking to new-age startups that promise the tools necessary to offer more peace of mind. We talked to Ted Schlein, a general partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and an investor in the cybersecurity space, about the industry’s future, what companies can do to shore up their defenses, and more.

“There are only two types of companies in the world: those that have been breached and know it, and those that don’t,” Schlein said. “There’s not a company around that if a bad guy wants to get in, they won’t. You can try and make a high and mighty argument that ‘you can’t touch me,’ but it won’t happen. You have to change the method and make the breaches irrelevant.”

AI Scaling Hits Its Limits

Power caps, rising token costs, and inference delays are reshaping enterprise AI. Join our exclusive salon to discover how top teams are:

- Turning energy into a strategic advantage

- Architecting efficient inference for real throughput gains

- Unlocking competitive ROI with sustainable AI systems

Secure your spot to stay ahead: https://bit.ly/4mwGngO

On being a cybersecurity startup

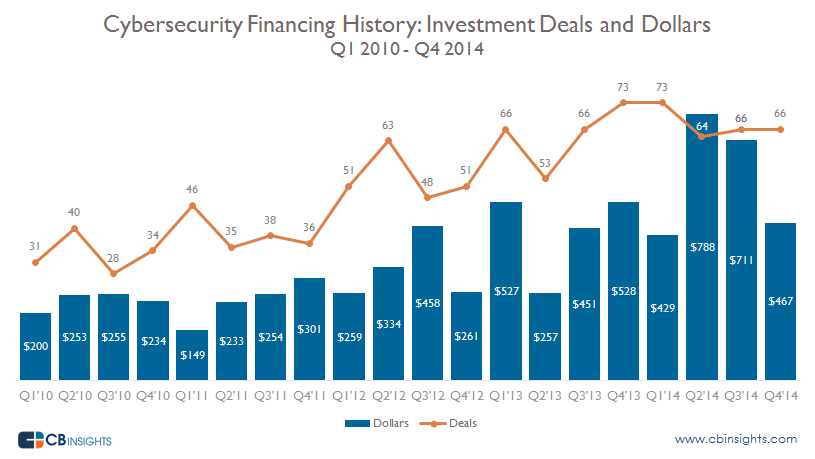

As more cyberattacks take place, government officials, companies, and investors are looking to startups for answers. Earlier this year, CB Insights reported that in the past five years, 1,028 investments were made in private cybersecurity startups, totaling $7.3 billion, an amount that didn’t seem to surprise Schlein.

“No one wants to be less secure,” he said. “The innovation of the bad guys is rapid. They have unlimited amounts of time and capital. Our ability to combat is lacking.” Investors of all sorts have funded companies looking to be the next big thing in protecting infrastructure. “It’s where a lot of IT budgets get spent, or it’s one of the areas that doesn’t get cut, and for good reason,” Schlein reasoned, but added a note of caution: “I don’t think that means more cybersecurity startups will be successful.”

Working in a cybersecurity startup is something Schlein should know a lot about: He was the founding CEO of software security startup Fortify Software before it was acquired by HP, and also helped Symantec launch its antivirus solution. At KPCB, he’s the person behind the firm’s investment in Mandiant, LifeLock, Internet Security Systems, and others.

With the growth in the number of companies in this field, a lot of them start to sound the same. A challenge Schlein said these startups face is getting the first 10 customers, especially without looking like a “me too” firm. Not only that, but stealing relationships from incumbents that already deal with global companies is difficult.

However, this shouldn’t dissuade entrepreneurs from entering the space, because incumbents have trouble innovating internally. Instead, companies like Symantec, HP, and Cisco may recognize that young startups are outdoing them and make a move to acquire them. “Some of them will recognize value in these startups and say ‘I got to get me some of that’ and acquire it, and some of (the startups) will fight it off and say they want to be the next big incumbent,” Schlein said. “I think these big guys realize that there’s money to be made here. ‘We’re not the greatest at innovating, but these young startups are.'”

A new philosophy on cyberattacks

But rather than focusing on defending against intrusions and being reactive, companies should look at how to target the root cause. “If the existing stuff that’s been deployed isn’t really working, as measured by the number of breaches and dollars lost, you have to change the game,” he explained. “You’re moving from a way of prevention to detection. What the real job is is to detect and then remediate as fast as possible.”

It’s not about “snipping at the edges” of the problem, but rather discovering the underlying reason for an attack. Schlein believes that the old model of signature-based methodology (understanding what’s bad and preventing it) is outdated. Instead, companies should be focused on understanding behavior and doing more data analysis.

“The more holistic point is: How do you gather data — network, endpoint, log, event, and all the data you can — aggregate it, correlate it, run it through some models, and be able to say ‘Something isn’t right; this endpoint isn’t behaving in the way it normally does’ … as a way to localize and identify where the problem is,” he remarked. “That’s the big new approach. There’s a lot of people doing this, including IronNet, which is run by General (Keith) Alexander (former director of the National Security Agency). It’s a large undertaking and a huge approach.”

Many breaches are the result of someone complying with an email phishing for information. Schlein said it’s not possible to prevent this from happening, so companies often focus on the payload (what gets downloaded behind the scenes). But he thinks another way we should be looking at things is by tackling the delivery mechanism: “Can you get rid of the phishing message and take the defense to the attacker, and that way you’re never dealing with the payload?” In his view, this would be a fundamental invention that would raise the stakes for the bad guys.

Perhaps a “good” effect of the frequency of cyberattacks is raising awareness of security within the corporate space. Schlein told us that security breaches have moved from being a tactical operational issue, where it may have been viewed as a nuisance, to being a board-level conversation whose consequences could include impugning a brand and degrading shareholder value. He referenced the firing of Target CEO Gregg Steinhafel after the company’s data breach, calling it a “seminal event in the world of cybersecurity” and that it “forever made cybersecurity a topic of a boardroom.”

The rise of the chief security officer

Companies can no longer bury cyberattacks and instruct their chief security officer or engineering teams to just fix the problem. The impact is far-reaching, and boards are spending money to protect their data as best as they can. Schlein believes that the real question companies must ask is how exploitable they are versus how secure. The former involves providing information to boards about how vulnerable systems are to internal and external forces and how answers are provided. The latter is about what security measures you have in place, not necessarily focused on openings.

Right now, boards are asking CEOs about how secure they are, but they’re not getting the detailed answers they need to protect companies. Schlein said that chief security officers are going to be the “rockstars of the future. You’re going to see CSOs on public boards (who) will be some of the most highly paid employees in a company, and for good reason.”

The CSOs will be at the forefront of protecting a company’s infrastructure and data, essentially being the watch commander — standing at the wall, waiting for invaders to try to break into the castle.

Above: KPCB’s Ted Schlein (far left) at TechCrunch Disrupt SF in 2013 discussing cybersecurity technologies.

Consumers just want it to work

While most of our discussion concerned what companies could do to counter cyberattacks, Schlein also spoke about whether security startups will start to build more tools for consumers. He said that it’s a much harder market to really crack because “consumers want to be secure, but they don’t want to do anything to be secure.” They want the experience to be frictionless, without security measures impeding their ability to do what they’ve come to the app or website to do.

“The reason why the fingerprint sensor works so well on the iPhone is because you have to press the button to power it on,” he said. Startups should enter this market with “great constitution.”

Although Schlein is a venture capitalist now, that hasn’t stopped him from thinking about companies he wants to start. It’s part of his philosophy: If he sees a problem and no one is working on a solution for it, he’ll go build it. In fact, one of the things he said he’s working on is a product to provide people with an “unassailable” identity protection service similar to a real passport — if you can have that type of security offline, why can’t you do it online?

“You have to think differently so you don’t burn the consumer,” Schlein warned.

It’s likely that in the future, we’re going to see more of cyberattacks and security breaches at various companies — in fact, just while I was preparing this article, the Hello Kitty website and Livestream reported unauthorized access incidents. But there are plenty of other recent incidents, such as the breach of kids’ data at electronic learning product maker VTech. So as Schlein pointed out, instead of playing defense, companies should execute an offensive strategy and target the root cause of the problem.