I’m CTO of a mobile marketing attribution company. Recently, while upgrading our fingerprinting algorithms, we uncovered an anomaly that truly affects all players in the mobile industry from developers and publishers to ad networks and attribution companies. In this post, I’d like to outline exactly what this anomaly looks like, and how those of us involved in attribution can beat it together.

Over the past several years, we’ve addressed various forms of fraud as a continual investment. The upgrade in question was a routine tweak to our fingerprinting. Fingerprinting matches an advertisement click to an app install through a variety of methods. Before we deployed our upgrade, we estimated that a total of 10 percent of all fingerprint-based app installs, which in turn make up around 5 percent of all app installs we see, would be rejected on the basis of the new algorithm. Given this seemingly minimal impact, we deployed the changes to our production system.

What we discovered upon deployment is that the impact was disproportionately distributed across ad networks. Some ad networks had conversion rates dropping from 0.X percent (click-to-install) to 0.0X percent, which was exactly the factor by which we improved the fingerprinting. Installs previously attributed to clicked ads were discovered to have never actually been driven by those millions of clicks – they were in fact organic user-generated installs randomly claimed by ad networks by spamming the fingerprinting algorithms. By sending hundreds of millions of clicks for a single app, some of these ad networks had claimed a good part of the organic installs for an app.

The most effective name for these types of fraud campaigns is “click spam.” In terms of total user volume, these campaigns are dwarfed by legitimate traffic, but they’re still large enough by a long shot, and so unevenly distributed, that they can move millions of euros from the app developer’s pocket to a shady fraudster.

Fraud: A Rapidly Expanding Market

In the app economy, growth is a major driving factor with hundreds of millions of impressions-per-second leading to billions of clicks-driven-per-month. In September 2015 alone, we received over 16 billion clicks from our partners. Yet, according to Gartner research, there are roughly 2.5 billion smartphone units worldwide. Some quick back-of-the-napkin math would tell us that the number of clicks we are receiving from partners vastly outnumbers the number of potential smartphone users who would be clicking on ads in a given month.

The clicks themselves are uninteresting — app developers are optimizing for installs, and typically paying on that basis as well. Diving deeper, ad networks or their fraudulent publishers are sending these clicks in the hope they can claim a share of an app’s organic user installs. Those users will look like quality traffic if they convert and retain exactly like organic traffic. In its most extreme form, this type of click fraud works by just sending lists of devices as clicks and hoping for the random chance of a match, no matter how low. The conclusion: Ad networks are falsely claiming ad clicks that map to installs.

Who’s to Blame?

This particular click fraud scheme is the product of not only the ad networks, but also the countless fraudulent publishers that deliver inventory to the networks. The fraud is conducted through a combination of sending impressions as clicks, or constantly clicking in the background of an app, or even blatantly sending made up clicks from catalogs of collected device IDs. Unfortunately, ad networks are faced with the decision to use this highly profitable inventory or cut their own revenue by a significant share, and the victim of fraud is the developer paying unnecessarily for this traffic out of pocket.

Resolving this Scheme Across the Industry

All tracking companies receive fraudulent clicks because these schemes typically work. We can make a big dent, but there isn’t a single attribution system in the industry with large enough market share to shut down click spam altogether. Instead, we must broadly address how the industry matches clicks to installs.

How can we stop attributing an ad click that is coming from an actual phone with a matching device ID? The answer is astonishingly simple and easily implemented – so much so that we encourage all attribution companies in the market to start implementing their own version of our approach as soon as possible.

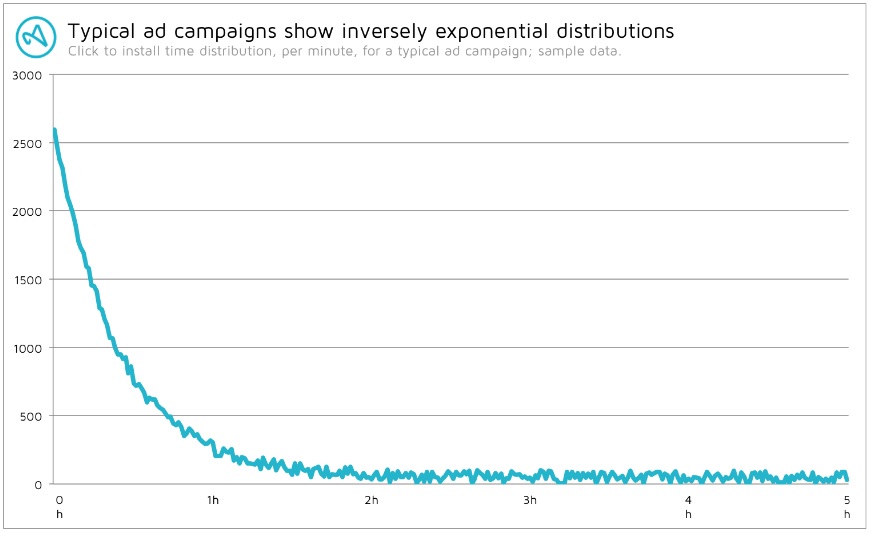

When a real user clicks on an ad and is presented with the app store, they typically download an app immediately. This leads to an inverse exponential distribution of installs over time:

We can simplify this by grouping this into hours after click, giving us a graph like this:

This gives us a normal distribution where apps have at least 50 percent of their installs after the first hour and 60 percent after the second hour, with games coming closer to 90 and 95 percent.

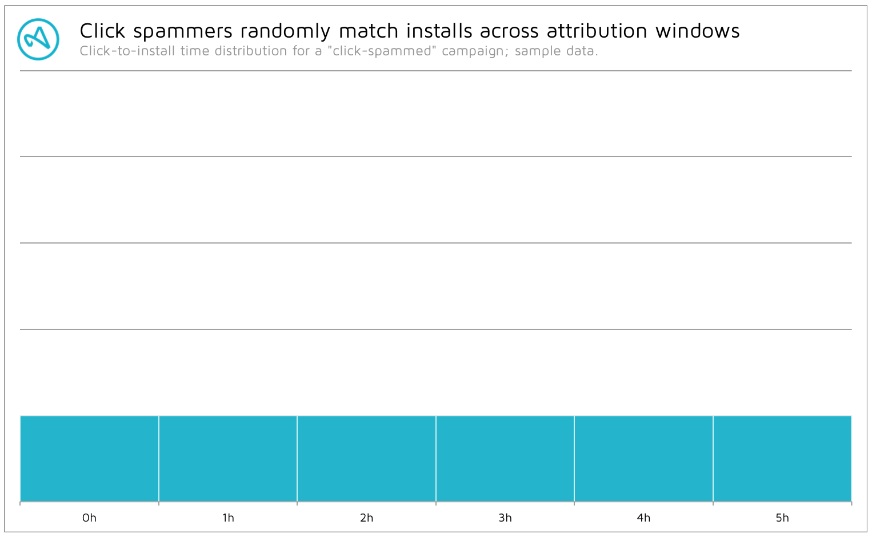

Now, a click spam campaign doesn’t actually send the user to the app store and thus won’t show this behavior. Randomly matching users will create a more or less flat distribution of installs over time:

Storing the distribution of matched installs (and those that “would have matched”) for a campaign allows us to check if a new install that we are about to attribute fits a “healthy” campaign pattern or not. For example, if the current 0h group has only 10 percent more installs than the 1h group, it makes sense to reject an install and to attribute it as organic if it happened within the first hour after the click. We should only attribute when the distribution looks normal. This way, campaigns with a flat distribution would not be able to claim any installs beyond a very basic threshold used to train the matching. Combining this with the typically low conversion rates below 0.1 percent and click numbers in the millions, we have a surefire way to broadly block an entire cottage industry of fraudsters.

We’re testing this now, and our early results are showing the exact same tendencies as our fingerprinting updates. The reduction in matched installs is disproportionate across placements and across networks. That means it’s working.

3 Key Takeaways Today

1. Among the many types of fraudulent mobile ad campaigns, click spam is the most insidious because app developers can impossibly tell these campaigns apart with standard tools.

2. Despite click spam’s pervasiveness, there are easy solutions that we can implement today that, from simple statistical observation, can block this approach outright.

3. We can only be effective at destroying this, and other forms of fraud, if all major attribution providers play along.

The Best Course of Action Now for Developers

If you’re an app developer currently buying inventory with conversion rates below 0.1 percent, I urge you to have a look at those metrics to see if you may be effected by click spam campaigns.

As soon as we as an industry can resolve click spam, the next phase of fraud that we will need to address will be simulated or faked installs. This will have another solution (rejecting proxy/cloud IPs), and again, it’ll only work fully if all tracking providers catch up on the scheme.

While it’s true that fraud prevention is a constant game of catch-up and cat-and-mouse, we still don’t need to completely destroy fraudsters to win the battle. The more realistic goal for all parties in this ecosystem (developers, publishers, networks, and attribution companies alike) is to raise the cost of fraud to a level where diverting resources to other targets becomes more profitable for the criminals we are up against. As an industry, we should always have an eye out for the next level of fraud and be proactive when possible to shine a light on the shady side of the market.

Paul Muller is CTO of Adjust.